To understand Tina Girouard’s works requires a nuanced care for the documents of and around her performance, new media, and sculptural works. In the following interview, Andrea Andersson, Jordan Amirkhani, and Jade Flint of the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art & Thought in New Orleans embrace and wrestle with the ephemeral nature of Girouard’s poetic signs and systems, experimentation across geographies, and ability to broadcast to communities in New York, Louisiana, and Haiti in the archive that composes Tina Girouard: SIGN-IN. Their curatorial perspective is notably grounded in the context of the South and the papers and material traces that carry forward Girouard’s legacy. But as Andersson, Amirkhani, and Flint convey, Tina’s worlding continues to bypasses a static past, instead casting audiences past, present, and future in her here-now.

This conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Laurel V. McLaughlin (LVM): As an entry point here from multiple perspectives, could each of you describe your first encounter with Tina Girouard’s work—your first “sign-in,” so to speak?

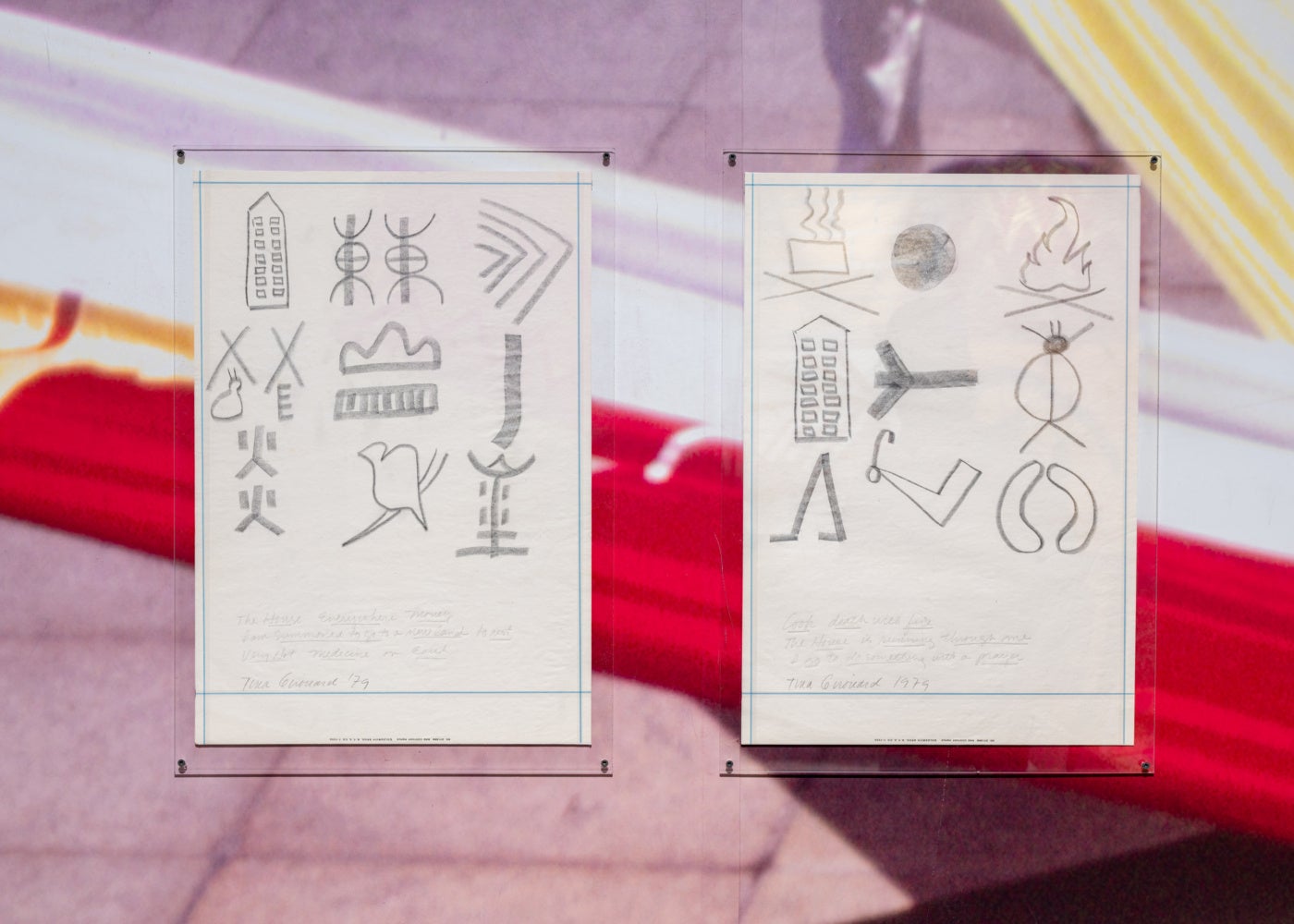

Andrea Andersson (AA): I first encountered Tina’s work as a child in the 1990s in Louisiana. I wholly misrecognized and miscontextualized the work. Her images circulated in what I understood as the New Orleans contemporary art context of the 1990s, which was not particularly interesting to me as a teenager. I was too young to fully appreciate the depth of knowledge that her glyphs and sign systems held, or her intentional use of false flags. My second encounter with Tina’s work was in graduate school, while writing on Gordon Matta-Clark. I found her in the margins. Twenty years later, I had a coffee with Jessamyn Fioré, which led to a trip to Lafayette. I never went looking for Tina, but she kept showing up.

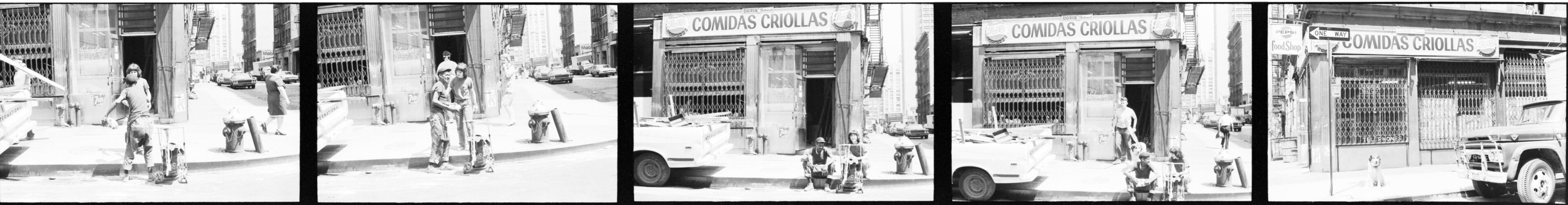

Jordan Amirkhani (JA): I didn’t know Tina Girouard’s work until Andrea began working on this project in 2020. I’m frustrated by that because I have a PhD in Art History and I studied the post-war avant-garde schools and movements; but I knew more about figures such as Carol Gooden, Suzanne Harris, and Laurie Anderson. This speaks to the burial of Tina’s work within American art histories and multiple genres of post-war American art, be that performance, video, installation, and Post-minimalist traditions. So, this project has deepened my understanding of histories of Anarchitecture, performance, dance, southern 70s, 80s, 90s art practices, and also made me realize how integral Tina’s work was within the scenes that she was actively participating in, such as feminism.

Jade Flint (JF): I also was not introduced to Tina’s work until I started working with Rivers. About a year into my employment, we started opening the archival bins from Tina’s estate, and I was just floored by the sheer amount of material—slides, correspondence, notebooks, and ephemera that Tina had kept since the late 60s. Through the process of organizing her archive, I started to learn more about her artistic practice and her collaborative network across her life.

LVM: How did you collaborate on this research initiative at the Rivers Institute for Contemporary Art & Thought? By way of delving in, what are your roles and how did the project take shape at Rivers?

AA: The holder of the archive is Jade—she was instrumental in digitizing the work. We inherited digital files materials from the Estate. But we began afresh with the primary material, both as a way of learning, and in order to sustain much of the original order, and Jade really held that for us. Rivers works in collaboration, so inventing systems and logics for this archive included borrowing strategies from other places and partners.

JF: Amy Bonwell, the Executor of the Estate and Tina’s niece, digitized materials and provided hard drives; so, there was some record of each performance. We had another research assistant, Mitchell Herman, who did some of the early digitization work; and I tried to mimic the systems that Amistad uses to digitize materials in order to build the archive into something useful for Jordan, Andrea, and researchers for our upcoming publication, Tina Girouard: SIGN-IN scheduled for release in 2025 by Rivers and Dancing Foxes Press.

LVM: As the first comprehensive retrospective of Girouard’s work in performance, film, textile, printmaking, and socially-engaged practices, how did you approach research in the Estate of Tina Girouard archives, and specifically the art historical claims to her work ranging from Post-Minimalism to the Pattern and Decoration movements, and even 1970s feminism? It strikes me that the exhibition eschews these neat categorizations.

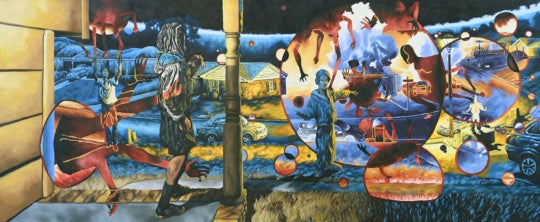

JA: One of the great gifts of Tina’s practice is that she was both aware of schools of thoughts; but, as we have all learned, there’s a tension between art historical thinking that’s neat and cute and artist-centric thinking that is often loose and unbound. Tina had very clear investments, but these moved and shifted. In the Ogden [Museum of Southern Art] presentation of the exhibition, we organized it chronologically, whereas for the CARA [Center for Art, Research and Alliances] presentation organized with Manuela Moscoso, each gallery felt like a constellation including various genres, moments, materials, and times. That, to me, felt like the truest presentation of her work. To say that she has specific relationships with say, Pattern and Decoration, it’s just not entirely accurate because she’s cared about pattern since the late 60s and 70s, way before that movement crystalized. A critique of minimalism and the large-scale masculine aesthetic has always been a part of her work as well.

JF: When I first encountered her practice, the decades felt dispersed—because I couldn’t understand how she went from doing performance in New York to sequin work in Haiti and how these two wildly different modes of working could be related. Once we saw the archive in its entirety multiple times, these themes throughout her career became clear.

LVM: Thank you for tracing these routes throughout Girouard’s circuitous practice. I’m interested in that “constellational” notion of archival presentation that you mentioned, Jordan, especially since I saw that clearly at the exhibition at CARA. Notes from Girouard’s collaborations with Gordon Matta-Clark and Carol Goodden for the 1970s Soho “Food” joined her activist efforts founding the Artists’ Alliance alternative space for contemporary art, organizing work with the Festival International de Louisiane in New Orleans and Haiti, and bold writings on interdisciplinarity and experimentation. In fact, Girouard expressed her desire “to have more than one thing happening at the same time…in performance, in my life, in whatever.” How does the exhibition’s centering of archival work articulate Girouard’s intense desire for simultaneity, interdisciplinarity, and multi-locationality?

AA: For Rivers, this project is distinct because we very often work with living artists, but this project foregrounded material history. Yet at some point, it stopped being a historical project, because we developed an intimacy with the material. It is true to say that the archive began to present as a sign system for now. We, of course, felt responsible for the art historical markers, but the archive can be read in the context of a moment in time, but those moments seem to be in rehearsal again now.

JA: I would also add that the role of the archive in this project is completely central as our guide. Tina put the learning in the archive. What was so exciting to me was, yes, there are these material works that you can display, but more so the fact that she was making and documenting in her own signature. The archive is a stylized presentation of her practice—almost as if the archive is the work that happen to have three-dimensional objects out in the world supporting it. I recognize that this is a provocative way of thinking about her practice; but as someone who really cares about the histories of the collapse of art and life, but often frustrated by how silly and absurd that is, as it’s not collapsed at the same time, particularly in male practices of the avant-garde. For Tina, there is a thin line between those things. The archive is the thin space between them. It leads you to the work, and leads you back to her and her communities. It’s not an accessory for private or public consumption; it’s a very particular third space in her work.

AA: It also gets to the idea of what Tina considered a sign. Lumi Tan wrote about how she was making signs through still photography of her time-based work. In the archive, her signs and writings about broadcasting out an image signaled something durational and sustaining.

I never went looking for Tina, but she kept showing up.

JF: To say that Tina had a musician’s ethic is entirely true. And throughout Louisiana, people tend to stay in contact with one another, and she did that with folks she met across the region and those further away in Haiti. It’s not something we see often in the art world for people to build partnerships intentionally beyond the artwork itself. Another important artistic strategy of hers is her research. From 1973 to 1974, she studies ancient glyphs from this text Sign, Symbol, and Script from Hans Jensen, which she took to Europe and developed through her travels in Haiti visiting temples and conducting studio visits. She wasn’t only drawing on her own experiences, but instead employing research alongside community engagement and broadcasting it out.

LVM: Girouard was socially aware in an era of immense global expansion through technologies and mobilities, especially in the west. Her practice foregrounded interconnectivity. How was Girouard rendering locational practices with communities and simultaneous dislocation throughout her practice—could you share some of her artistic strategies and perhaps how the archive describes these?

AA: Tina also called herself a “tape artist” at some point. I kept considering her dialogues with writer and filmmaker Liza Béar, and how different our knowledge would be without those transcripts. She talked at length with Liza for radio from Louisiana. These dialogues were then aired in New York, then it was published in Avalanche—displacing and forging audiences through technology. Her audience and context shifted radically through new modes of circulation.

JA: Part of this project was to do a cycle of interviews with Tina’s peers and colleagues. I never got to meet her, so we all wanted to learn from people who cared about her. She maintained this group of collaborators who were artists and were also a part of this intellectual group with her whether in Louisiana, New York, or Haiti. She was the connector keeping it together. Richard (Dickie) Landry, her husband and also an improvisational jazz musician and early member of the Philip Glass ensemble; and, I think she has a sense of improvisation in the musician’s ethic about community. You play with your band, and even if you’re not physically together, you are. The history of art is an individualist model, but jazz is not. So, that spirit informs her own community building and networking.

AA: Yes! And also, I want to add that this past weekend the three of us were together for another Rivers project with members of Bvlbancha Liberation Radio, at the Nanih Bvlbancha, a mound recently-constructed by an intertribal community in Louisiana. One of the members was talking about their radio work and described the mound as one of the antennae. For me, this resonates with Tina’s work. She moved between what she understood as ancestral knowledge and contemporary technologies. When she worked in other cultures and communities, she would bring things with her, like the Solomon’s Lot, these silks that she was gifted from her family in Southern Louisiana that traveled across the world with her. They became receivers of frequencies that traveled distances.