“You get so overwhelmed by the hordes. You start thinking of people as cattle. Screaming kids. Hot, tired people at their ugliest.”

Year after year, despite relentlessly scorching summers, unpredictable hurricanes, and, even now, a pandemic, the Magic Kingdom at Disney World in Orlando, Florida, is the most visited theme park in the United States. The lack of critical regard for the city of Orlando as a cultural site, while disappointing, is not surprising: Orlando barely has a coherent identity as a city independent of Disney World. Intellectuals and artists raised in Orlando are the first to move elsewhere, often to areas with vibrant histories and the kinds of resources they provide—vast libraries, museums, historic sites, graveyards. The patently artificial is flatly disregarded, as if incapable of producing something we could reasonably (if not proudly) call culture.

I share my delight in Florida’s garish taste for recreation and general waywardness with nearly everyone who has ever set foot on the state’s sand, mud, or concrete, but Orlando represents a distinct state of leisure altogether. In the shadow of Disney World, Orlando has been artificially manufactured to sustain what is, of course, unsustainable: limitless, all-encompassing enchantment. Borders, margins, and peripheries have covert significance for this landscape in which they are strictly policed but designed to remain unseen. Since opening in October 1971, Disney World has induced the irrevocable transformation of Central Florida from a low-density, citrus-growing region into a trademarked international destination for vacationers.

1. Project X; or, The Florida Project

Shortly after the opening of his first theme park—Southern California’s Disneyland—in 1955, the desire to build a second theme park occurred to Walt Disney. Numerous expansions occurred in the California park after its initial opening date, suggesting a property with more than enough space to accommodate what is essential, but the animation pioneer wanted scale—miles and miles of acreage insulating his commercial fantasy from everything external to it. Florida held the promise of year-long seasons for sunny, uninterrupted operation, and there was plenty of open land. Orlando, in particular, held the special allure of having pre-existing highways.

The story of Walt Disney’s degenerate Floridian utopia begins in resolute secrecy. He was determined to build not only a fantastical amusement park but also a fully planned community, and, in its latency, developing his “city of tomorrow” required both silence and finesse. Then there was the cut-and-dry matter of grabbing as much land as possible for eighty dollars per acre before landowners and speculators realized who was coming to town.

“Project X”—or “The Florida Project,” as it came to be known—was carried out in the strictest confidence by a small selection of professionals from the fields of real estate, law, and military intelligence. Pseudonymous entities purchased land through dummy corporations, carefully avoiding detection by local and state governments. It wasn’t until Disney was already in possession of 27,000 acres of swampland that Emily Bavar, a young reporter from the Sentinel Star, the newspaper which would become the Orlando Sentinel, caught him off his guard at a press gathering in California. According to Bavar, when she asked Disney if the rumors that he was behind land purchases in Central Florida were true, he “looked like I had thrown a bucket of water in his face” [1]. The headline of the Star’s October 24, 1965 follow-up on Bavar’s reporting read “We Say: ‘Mystery’ Industry is Disney.” Less than a month later, Walt Disney and his brother Roy held a press conference at the Cherry Plaza Hotel in Orlando to announce their plans to build an entertainment venue in Central Florida.

All told, Disney’s Orlando property is forty-eight square miles, slightly larger than San Francisco and more than twice the size of Manhattan. In 1966, Walt Disney Productions petitioned the Florida state legislature to grant the company total municipal jurisdiction over the land, thereby creating the self-governing Reedy Creek Improvement District. The enormous lot of swampland was intended to be the site of the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow (EPCOT), Walt Disney’s never-fully-realized dream of a “pristine” community enhanced with technological innovations. But Walt Disney died before the end of the year, and plans for the utopian city were abandoned.

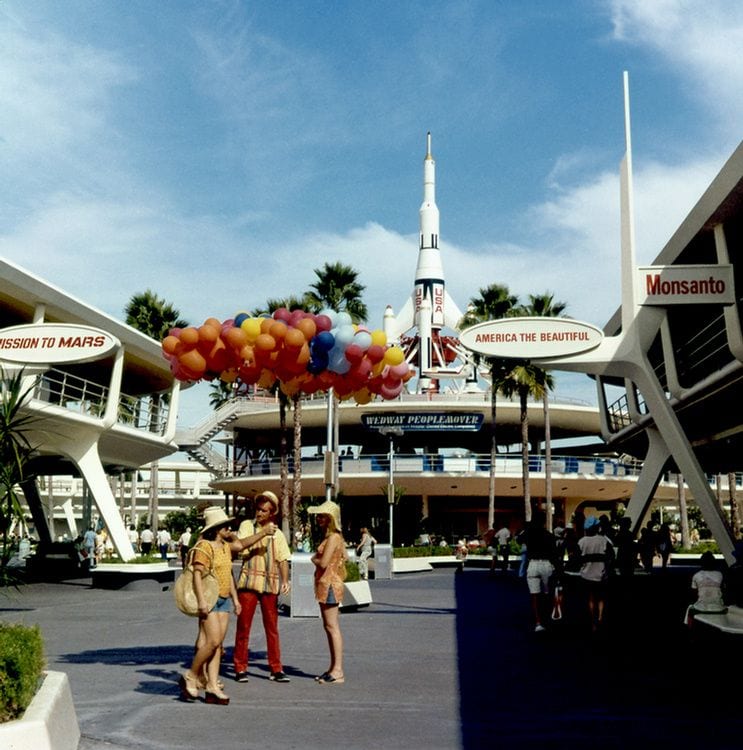

Today, Epcot is no longer an acronym and hardly a vision of either “community” or “tomorrow,” but its attractions do prominently advertise insidious alliances with corporate giants such as General Motors, Verizon Wireless, Siemens, Exxon-Mobil, IBM, and Hewlett-Packard, among many others [2].

2. Lighting Up in Fantasyland

Due to the secrecy surrounding Walt Disney World’s inception, its ceremonious opening in 1971 didn’t clearly foreshadow the dangerous economic dependence on the park that followed. My mother, Lisa, and my uncle, Craig, both born-and-bred Central Floridians, sought employment at the park as soon as they knew where to interview. In 1972, Lisa was a senior in high school and Central Florida was all orange groves and plant nurseries.

“[Disney] had a construction trailer as an employment office,” she recalls. “If you could walk and talk, read and write, you got a job.” Lisa and Craig’s parents owned clothing stores in the heart of Winter Garden, about twenty miles northwest of Disney World (everything in the greater Orlando area is about twenty miles from Disney World—by design). Their parents’ livelihoods and the businesses of many, many other locals were gradually devastated by the onslaught of retail franchising in the wake of Disney. But in 1972, for most local youth “[Disney World] was a godsend,” Lisa says unequivocally. “I had been working at a florist’s shop making $1.45 an hour. Disney started at $1.75 an hour. That’s a big jump to someone in high school. And I was lucky to get that job with the florist, but there weren’t that many jobs around; you either worked at a soda fountain or a gas station or some little retail—I mean, where would teenagers go back then? There were no malls or anything. So when Disney opened, they hired everybody, everybody who applied. And everybody thought it was just wonderful because Disney’s paying forty cents over minimum wage.”

In 1972, Lisa started working as a cashier in the endlessly chaotic Liberty Square Main Street Emporium and transferred, as soon as she was able, to working in Disney’s tram parking lots. “The parking lot was a blast. The people I worked with were irreverent and didn’t follow the party line, which I liked because I was just starting to break away from what a good little girl should be. I found some wild people to hang out with in the parking lot,” she told me. “Visitors stopped arriving around five o’clock. It was much slower from six to ten, so when we had an empty tram, we turned it into a whip. We knew if there weren’t supervisors around that we could drive around the parking lot planters and trees trying to throw off the person on the last car. We’d hang on for dear life while the driver tried to whip us off. Yeah, it was stupid and dangerous, but what else are you going to do when you’re eighteen?”

Occasionally Lisa would be assigned to drive vans of employees to and from the center of the park. There was a lonely, wooded road around the perimeter, stretching about seven miles from the parking lot to Cinderella’s Castle, underneath which was located the subterranean wardrobe department frequented by every Cast Member in the park. As soon as Lisa reached one end-point, she’d have to turn around to make another trip. Back and forth she went, every ten minutes. According to Lisa, most park duties have a similarly mind-numbing effect on employees. “Once a week, everybody that worked in the parking lot would get together and walk over to the Polynesian with flasks from our cars. We’d get shitfaced on the beach.”

After some time working in the parking lots, Lisa transferred to Tomorrowland (considered the “bottom rung” of attractions at the time), and then waitressed at the Diamond Horseshoe saloon in Frontierland. Despite offering the same wages, working at the saloon was a prestigious job within the park. Very few people worked in the saloon and the women wore can-can costumes and fishnets. Called to work unexpectedly on New Year’s Eve, Lisa and another waitress requested “door duty” and enjoyed a delightful late shift in the Magic Kingdom under the influence of magic brownies. “I’m sure that happened a lot,” she says. “The place to get high in the park was always the gondola in Fantasyland—that was code. Go to the gondola to light up. That was the only place where a security guard might not smell it. Craig’s job at the Haunted Mansion was to move through a series of hidden locations to catch smokers. All the attractions had spotters because that’s where people were smoking.”

By 1975, Lisa had moved on to working at a fish camp in Canada’s Northwest Territories—just about as far away from the physical and psychological space of Disney as possible. “You get so overwhelmed by the hordes. You start thinking of people as cattle. Screaming kids. Hot, tired people at their ugliest. You develop a disdain for humanity. It just changes you.”

“Cattle” becomes a prominent image for Disney World guests too, as they spend the vast majority of their park time waiting in lines. Simply traveling between the parking lot and Magic Kingdom requires two separate modes of transportation (tram followed by monorail, bus, or ferry) and often takes half an hour, not including time spent waiting in line to pay for parking or to purchase park admission. Wait time describes a whole continuum of amusement park experiences, but Disney World, with its seemingly endless series of transports, amenities, and attractions, has utterly transformed queue design into an occult science.

Magic and enchantment prevail when the sorcerer’s machines are well concealed; the rigorous application of circuitous distortion to both architecture and the landscape diminishes guests’ abilities to perceive real distance—an achievement which is naturally intensified by the topography of Central Florida, its uninterrupted sea-level horizontality. In the parks, every activity, every possible move, is fully accounted for and leashed under the direction of Walt Disney Productions.

3. Wait Time and Transitional Fantasy

Seen from the outside, Disney attractions have the showy fiberglass monumentality of stage sets, fantastically suggestive but patently false. Whether indoors or outdoors, queues flow through courses of compact chambers designed to thwart any comprehensive understanding of space. Meticulous care is given to narrative elaborations, which effectively build anticipation for the ride while distracting guests from the nihilistic character of wait time. Owing to the fact that their functional attraction spaces can be buried out of sight behind deceptive façades, the indoor “dark rides”—such as the “It’s a Small World” boat ride—particularly excel in conjuring an immersive immensity that is spectacularly at odds with exterior presentation.

Within the process of persuasive world-building, every immersive fantasy grants precedence to background, and the landscaping of Disney World demonstrates staggering feats of botanical engineering. Non-native tropical plants are standards of Central Florida landscaping, so perhaps we are less inclined to notice the fastidiousness of palms and grasses in Adventureland and Animal Kingdom—the wholly manufactured landscape is certainly meant to appear seamless and inevitable. When I revisited Disney World as an adult, with some measure of ecological awareness and curiosity for every detail, I was positively shocked by the crisp alpine meadows of Fantasyland thriving in relentless subtropical humidity as if protected by some magical barrier.

Within the process of persuasive world-building, every immersive fantasy grants precedence to background, and the landscaping of Disney World demonstrates staggering feats of botanical engineering.

Walt Disney World is exceptional among theme parks for deploying vast tracts of land and bodies of water as neutral easements carrying guests from “real” to “fantasy” worlds. The ferry, for example, is an entirely impractical way of arriving at the Magic Kingdom, but its effect of transporting guests across a metaphysical barrier into another realm (not always a pleasant one) is undeniable. To achieve this effect in accordance with an ethos of “pristine” presentation, Disney land development has involved dramatic alteration of the landscape through illusionistic hydrology (drainage systems carefully disguised as idyllic streams) and exhaustive grooming of marshy scrublands. To a similar effect, on average, it has been observed that a single article of trash remains grounded for less than five minutes—whereupon it travels through well-concealed vacuum tubes at sixty miles per hour toward a central incinerator.

Sanitized liminality in service of enchantment is used again to great effect across Disney’s geographies of nostalgia. The Splash Mountain log flume ride and Southern Colonial-style Haunted Mansion attraction maintain ambiguous relationships to history, refusing to signify either the Antebellum or Reconstruction era while borrowing freely from both. This is a point of some urgency because Splash Mountain, scrubbed of its historical context, allows Disney to continue to profit from its overtly racist, live-action/animated musical Song of the South, from 1946. Adapted from the collected stories of Uncle Remus—already deeply complicated and problematic, being African American folktales transcribed by a self-appointed white folklorist—the film romanticizes plantation life from the perspective of a young white boy being entertained by the tales of a former slave, who contentedly stays on the boy’s family’s plantation after the abolition of slavery.

Uncle Remus is an uncredited, disembodied voice behind some wall text in the Splash Mountain queue. With the monologue including bits such as, “The critters, they were closer to the folks; and the folks, they was closer to the critters. And if you’ll excuse me for saying so, ‘twas better all around,” there is more than a faint echo of nostalgia for the Antebellum South. Guests puzzled by this oblique apothegm in the queue (thirty minutes to two hours of wait time) experience a neatly revised narrative offered within the attraction (twelve minutes in duration). With an animated cast of “critters,” starring Br’er Rabbit, only the least controversial elements of Song of the South remain—although it’s curious that the most marketable aspect of the attraction, the song “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” is widely recognized as a throwback to blackface minstrelsy. Nevertheless, with Uncle Remus absent and the live-action framing story of the film erased, Splash Mountain is a testament to Disney’s ongoing mystification of an indefensible commodity.

Despite nearly two decades of gloomy predictions following 9/11, and pervasive and urgent pleas for economic diversification from the community, Orlando’s dependence on the leisure industry has actually grown. Today, because so many local residents are employed by a single company, the city’s greater metropolitan area is one of the most vulnerable to recession in the country. Under the influence of powerful lobbyists, public funds from tourist taxes are routinely funneled right back into the interests of private tourism, servicing the convenience of theme park guests rather than residents. As rich economic resources form closed circuits around the tourism industry, many Orlando locals are left to wonder, What riches? Where?

Presumption of innocence and presumption of emptiness seem inextricably linked here. How easily our scrubland can be leveled, and any fantasy built upon it! Meanwhile, developers across Central Florida demolish relentlessly, then name the thinly partitioned land after that which has been destroyed. The hawks are recently missing from “Hawk’s Crest.”

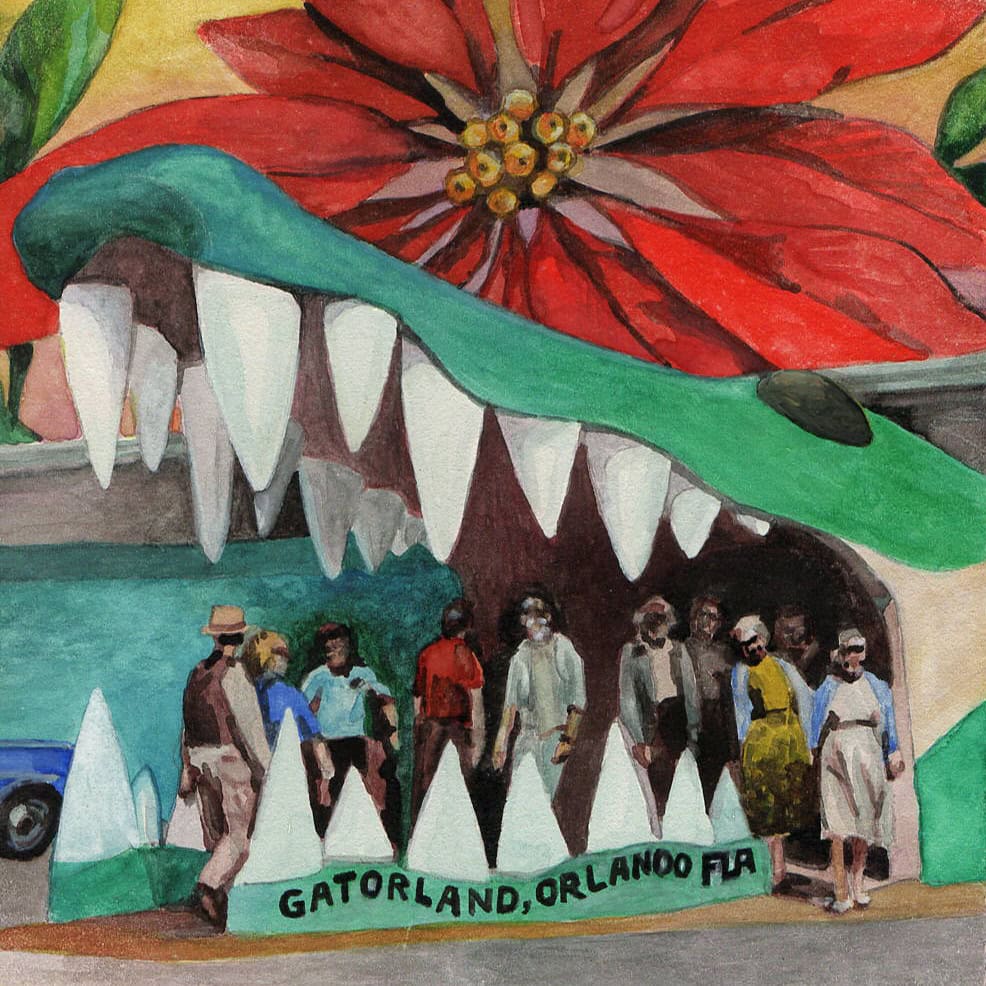

Growing up in a quiet suburb about twenty miles northeast of the theme parks, my friends and I understood that our sense of place amounted to an afterthought. We observed local ambiance regularly subordinated to the imported mythologies of corporate tourism. A unique feature of my public middle school’s “gifted” program was that our teachers plotted field trips around sites of historic interest—like the woods immortalized in Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings’ novels The Yearling and Cross Creek, or the childhood home of Zora Neale Hurston—rather than defaulting to corporate park junkets. Gatorland is one of the few, if not only, old Orlando attractions to have survived and even flourished since the pharaonic inception of Disney World; you can guess by its name that Gatorland retains some semblance of regional specificity: reptile fancy and the Florida cracker “style.”

For the past year, I’ve been living in an unincorporated suburb close to downtown Orlando. Behind my house, a spacious recreational trail traverses two counties, cutting a path between fenced and flowering yards, and finally emptying into the deserted parking lot of Fashion Square Mall. The past decade has witnessed millennial malls draw closer to the precipice of demise, and lately they really look like ruins. I love cruising on my bike through these empty parking lots. As cars periodically appear, I remember that the greatest defiance in Orlando—so great that it is almost impossible to perform—is being a leisurely cyclist or pedestrian, as if these activities belong exclusively to vacation resorts and beach towns. The cars own these streets.

But in these empty parking lots, graced by the mournful sighs of doves hidden amidst grave-looking oaks and anfractuous pines, I wonder about an Orlando divested from the unsustainable fantasies of the Kingdom, a city that develops a taste for reckoning with what is already here rather than importing a readymade dream of another place, a distant tomorrow.

[1] Pat Williams, How to Be Like Walt: Capturing the Disney Magic Every Day of Your Life, 2004; pp. 288.

[2] Sean Baker’s 2017 film The Florida Project provides a haunting corollary to this development in the history of Walt Disney World, as it poignantly depicts the parasitic relationship between Greater Orlando’s tourist corridor and an underprivileged population living almost surreptitiously within it.

This essay is part of Burnaway’s yearlong series on States of Leisure.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2020 here.