In the small-scale exhibition The Literal is Unimaginative—his first solo presentation—artist Davion Alston debuts new site-specific work at Day & Night Projects in Atlanta. The restrained, deliberate installations and works on paper serve as a prelude to two additional exhibitions Alston is planning for the near future that work in a continuous dialogue with each other.

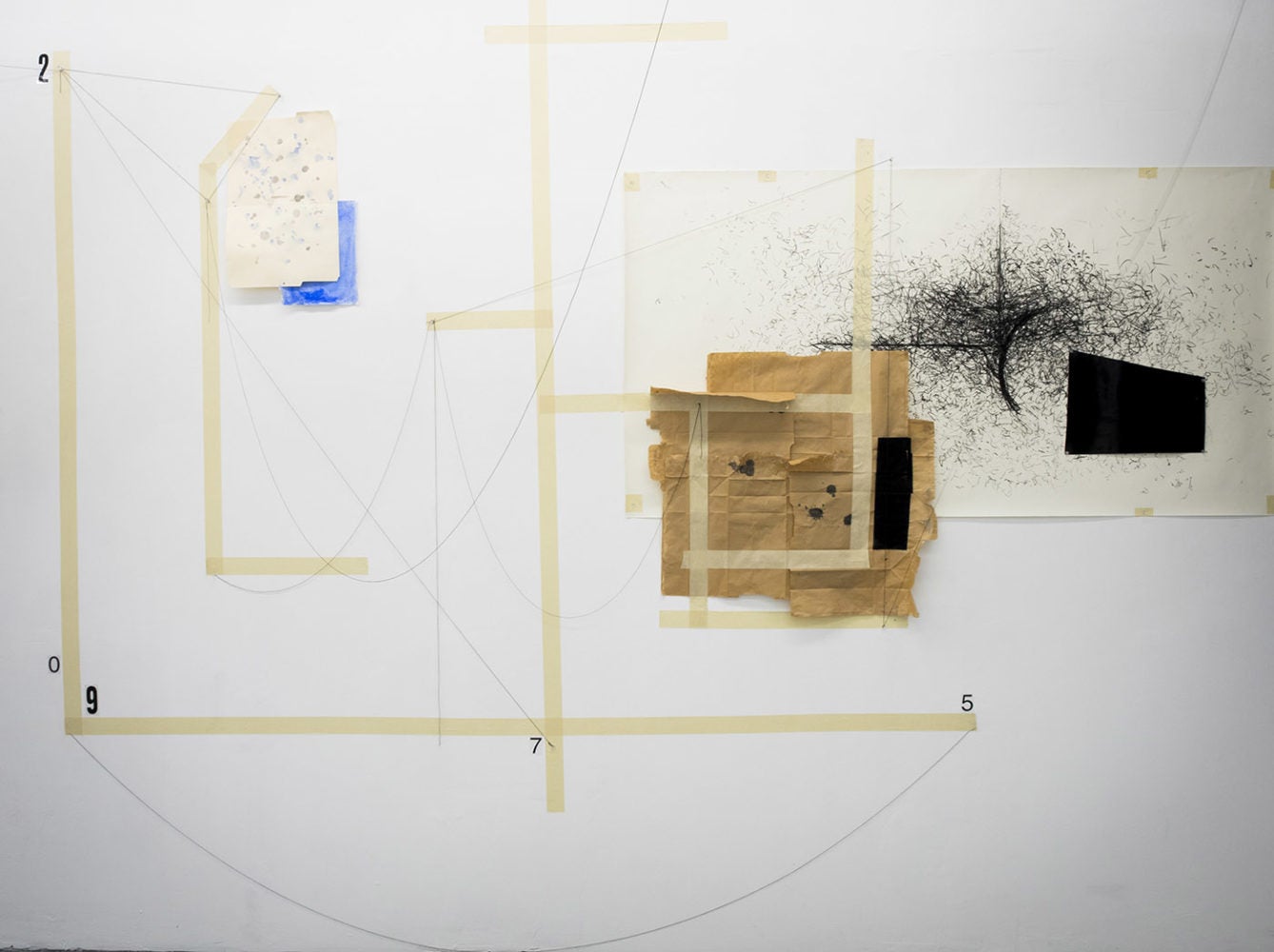

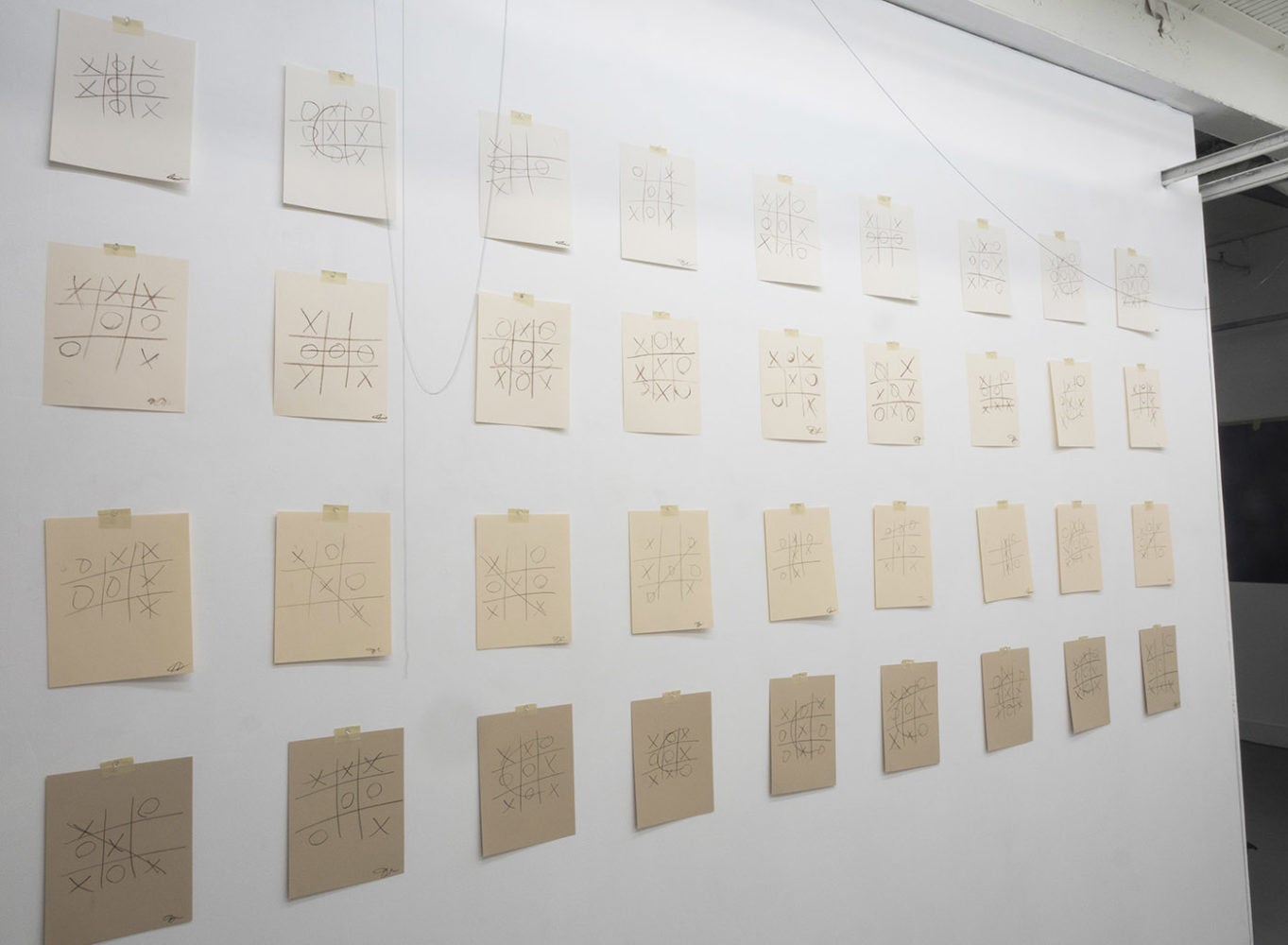

The artist’s new, increasingly abstract works draw on simplicity in gesture and significance. Incorporating sculptural arrangements of found objects, a video installation, and documentation of an ongoing game of tic-tac-toe that transcends space and time, the straightforwardness of Alston’s exhibition may tempt viewers to read more complicated meaning in the works than what he intends. With a sweeping arm gesture and an unbothered expression, Alston said, “It is what it is.”

Alston and I spoke in person at Day & Night Projects in October, and our conversation has been edited for publication.

Burnaway: What about the potential of Day & Night Projects attracted you to showing your work here?

Davion Alston: I definitely wanted the show to be in the West End, as my work confronts larger questions about the development of Atlanta and displacement of its residents. I’m interested in the idea of Atlanta as a terminus or a hub for transportation and the movement of bodies and goods. In this sense, Atlanta can be understood as a map that has become so abstracted that it can’t be read directly. What does it mean to constantly build on top of the structure of Atlanta? How does Atlanta contend with itself when we just put Band-Aids over potholes rather than fill them? What is the void that we’re trying to cover up rather than confront?

BA: How did these themes play into your former bodies of work? Did you similarly question Atlanta’s identity before or is this new territory you’re taking on with this solo show?

DA: It’s something new. A lot of my previous work came from questioning and negotiating identity within the self. As a Black person, I did not have the kind of representations that I wanted to see available in mass media or pop culture. My previous work was located in these tensions and often used my own body as a lens for reexamining these questions of representation and racial identity.

I’ve already investigated the self in relation to the gaze, the self under the surveillance of the camera. Now it’s just stepping into the bigger arena. Each work contributes to a broader inquiry that attempts to move through and, ultimately, beyond the question of what the self looks like.

BA: Although your earlier work was primarily based in photography, this exhibition contains virtually none. Are you moving away from the medium?

DA: I’m tired of the camera being the end of my process for conveying something. Photography has set the standard of how fast we expedite and desensitize ourselves to something. That bores me.

My earlier photographs questioned and negotiated the conditions that enabled a given image to happen. I’m not interested in questioning or negotiating things anymore. This is the work. This is the same work in other forms, where simple pleasures aren’t interrogated and simple actions like playing games, giving hugs and kisses, and other gestures can exist outside of what’s happing now in the larger world.

BA: You say photography bores you. What does it mean for an artist to be bored with their medium?

DA: Conventionally, we use photography as a vehicle for truth and to identify what the truth is, what it does, and what it means to be surveilled and have the “truth” imposed upon you. After a while, you tire of negotiating surveillance, of still seeing the evidence of certain things done to certain people in waves. We’ve reached a plateau of over-stimulus: too many images and not enough truth. The truth offered by a body cam in a certain situation, for example, may not be accepted as valid. You have the closest thing to evident truth, and still nothing shifts, nothing changes. What happens instead is the circulation and reproduction of those images, which perpetuates the same forms of violence and continues the same cycles. This process allows us to not only question truth but also creates propaganda. That’s why I’m bored with it.

BA: Am I right to say that this new body of work is about being present, finding presence through different mediums?

DA: It deals with presence in different ways, yes, but also with cathartic meditative gestures like scribbles. I’m interested in the indexical potential of drawing: tracing certain moments and allowing that to become the poetics of making. Not an image created by light written onto film, but something that has moved out from my arm. I love thinking about simple lines, the joys of expressionism, the pleasures of collaboration and games.

BA: What does that say about the lifespan of your art objects?

DA: With

photography, it was easy for me to give more of myself to the viewer than I

wanted to or even realized I was. Now I’m simply presenting objects. I’m

wondering what it means to have something—either a photograph or a literal

object—take the place of the maker. What does it mean to remove the imaginative

force behind a work and just present the object?

BA: Tell me about this body of work as it relates to your ongoing practice and future plans.

DA: I think this work is best understood as an incubator for my intentions. Instead of trying to force all of my ideas into one presentation, I wanted to break them up, divvy them up into multiple places. Among many other references and themes, the work illustrates or sketches out my ideas about displacement and queer theory. These common objects—manila folders, golf clubs, lines of string—can be understood as signifiers within larger frameworks of social and material infrastructure and movement. I’m trying to be more intricate with how I explore my identity through trajectories of displacement, adoption, and revelation. I’m very interested in making something so singular and self-reflective that, over time, it becomes a larger tool for questioning and challenging the identity of Atlanta.

BA: For your first solo show, you have chosen a space and a project that gave you a lot of autonomy, which many artists don’t have in their first solo shows. You picked the title and the space, for example. How does it feel to express this autonomy?

DA: I come to spaces wanting to do a project. I don’t apply to things hoping that I get them anymore—I just go ahead and put the artwork out there. Why not go ahead and use these spaces and utilize these resources? Let me go ahead and start intentionally mapping out what I want to do here. At this point in my life, it’s time for me to just do it and show up. Just make the work and show up and let whatever benefits come from that do so.

BA: This exhibition is you just showing up and doing the work?

DA: Yeah, but that doesn’t necessarily need to be profound. It is very simple, gestural.

Davion Alston’s solo exhibition The Literal is Unimaginative is on view at Day & Night Projects in Atlanta through November 2. Alston will give an artist’s talk on Monday, October 28 at 7 pm.