The Atlanta Biennial emerged in 1984 as Nexus Contemporary curator Alan Sondheim’s response to the lack of Southern artists included in the previous year’s edition of the Whitney Biennial. Between its founding and 2007, the biennial was presented intermittently and according to various frameworks: sometimes every two years, sometimes not; sometimes involving only Atlanta-based artists, or Georgia-based artists, or artists from across the American South. In August 2016, when the biennial was mounted for the first time in seven years, its curatorial team and artist roster were packed. In addition to Atlanta Contemporary curator Daniel Fuller, former Art Papers editor Victoria Camblin, New Orleans-based curator Gia Hamilton, and Jacksonville-based curator Aaron Levi Garvey assembled works by thirty-three artists from states including Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee. For the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, Fuller was joined by a single co-curator, Phillip March Jones, founder and curator-at-large of Lexington, Kentucky-based nonprofit Institute 193, which recently opened a satellite location in New York’s East Village. I spoke with Fuller and Jones about the development of the biennial during the weeks surrounding its opening. Our conversation was conducted via email during January 2019 and has been edited for publication.

Logan Lockner: In the statement accompanying the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, you refer to the artists included as being “inside and beside the larger art world,” a fitting characterization of the multiple, overlapping identities occupied by artists working in the American South. Can you speak a bit more about this description? The exhibition Outliers and the American Vanguard (previously on view at the High Museum in Atlanta and now on view at LACMA in Los Angeles) offers one sort of approach to viewing and understanding this “inside and beside” position, for example, by tracing connections between the work of self-taught and folk artists and that of more conventionally canonical American modernists. How might we approach the work of living contemporary artists with a similarly capacious, undogmatic spirit?

Daniel Fuller: I was recently listening to an episode of Freakonomics Radio called “Where Does Creativity Come From (and Why Do Schools Kill It Off)?” and was blown away by an exchange between Stephen Dubner and Ai Weiwei:

STEPHEN DUBNER: I don’t understand why you’re not in prison in China. It sounds like—obviously they did it for a little while.

AI WEIWEI: I’ll tell the truth. I tried to think about it and suddenly, just this moment, I realized the answer. The jail in China is not large enough to put me in.

DUBNER: What do you mean?

WEIWEI: I’m just too large for them. My ideas penetrate the walls.

Beautiful sentiment, right? Can we say anything different about Jessie Dunahoo? His ideas penetrated rural Kentucky. His ideas penetrated his disabilities. He is one of the greatest artists I’ve ever had the privilege to encounter, thanks to Phillip and Institute 193. I approach his work just like I would approach that of Ai Weiwei. There may be a difference in fabrication budgets, but the ideas behind the art of both are too large to contain.

Phillip March Jones: I’ve dedicated the past ten years of my life to advocating for artists, writers, and musicians whose works do not easily fit into the mainstream narratives of cultural and art history. Education, race, sexuality, geography, or the existence of a perceived disability continue to play an outsized role in the appreciation of works made by artists who are not on a proscribed, typical career track. I’ve always maintained that our collective approach to any art work should essentially be the same, and we should evaluate a work’s content, form, and quality based on its value to our understanding of the human condition and our place in the cosmos.

LL: Last year, the tenth edition of the Berlin Biennale took its title, We Don’t Need Another Hero, from the Tina Turner song featured in the 1985 movie Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. The curatorial team spoke about using this title as a way to “[confront] the current widespread states of collective psychosis” and “draw from a moment directly preceding major geopolitical shifts that brought about regime changes and new historical figures.” In many ways, when the previous edition of the Atlanta Biennial was presented in August 2016, it opened in a different world than the one we live in today, during a historical moment that seems, in retrospect, like a tense twilight hour. The title of the 2019 edition of the Atlanta Biennial, A thousand tomorrows, takes a markedly more optimistic approach to our seemingly post-apocalyptic moment than last year’s Berlin Biennale or New Museum Triennial, for instance, which felt more like sustained reactions to the global traumas of 2016. What does this exhibition’s implied enthusiasm for the future indicate? Have we endured the dark night of the soul and begun to glimpse a new day?

DF: When I was five years old, my dad brought me to a drive-in to see Empire Strikes Back. He realized he got the show time wrong when a young Mel Gibson, “the man we called Max,” was standing in an Australian wasteland. The narrator tells of a firestorm of fear, of men feeding on men, as graphic depictions of war flashed on the screen. The wheels of our station wagon kicked up dirt as a we sped away while, onscreen, a woman carrying a baby was run down by a motorcycle gang. We were mistakenly at Mad Max 2: The Road Runner.

Aside from that, we live in a difficult time. Today we face pervasive racism and sexism, global shifts in migration, the emergence of #MeToo, disparities in pay and opportunities and education across race, gender, and class—these are not new issues. The tone of the country right now can be dark, understandably. So I do what I always do: retreat to art. The artists in this show were making art before August 2016 and will be making art long after the sun comes back up on this tough period.

PMJ: The title A thousand tomorrows is not particularly optimistic—after all, a thousand tomorrows is only slightly longer than three years—but it certainly does not engage in the current doom and gloom that appears daily in the current twenty-four-hour news cycle. For me, it is meant to be a reminder that we all have to wake up and face each day, for better or worse, and speaks to the commitment demonstrated by the artists in the exhibition, who have devoted their lives to a daily practice of art-making despite some very present obstacles.

LL: There are a few changes in the scale of this edition of the Atlanta Biennial in comparison to its predecessor. Perhaps most obviously, it’s curated by a two-person team instead of a four-person one and includes twenty-one artists, twelve fewer than the 2016 edition. Did you find yourself making decisions based on finding alternatives to what has been done before, or was this simply the result of an unselfconscious, new process?

DF: I loved the 2016 Biennale. It was extremely ambitious, and after nine years of it lying dormant, I believe we revived something very important for the region. That said, looking back I have my own criticisms of the show. The curatorial team wanted to celebrate this incredible cultural landscape all around the South. It was a packed party with a lot of artists showing shoulder-to-shoulder. The art on the walls was beyond strong, but in my mind, I just wish we could have allowed more room for artists to stretch their arms. During the first conversations I had with Phillip, I mentioned my hope to scale back the artist list and give folks more room to breathe. Aside from that, the process was the same as 2016.

LL: A striking number of Kentucky artists are included in this year’s biennial, perhaps unsurprisingly given Phillip’s deep connections to the state through Institute 193 in Lexington. Phillip, can you provide some context for the recent history of contemporary art in Kentucky in particular, and how it connects to larger regional and national art worlds?

PMJ: The 2019 Atlanta Biennial does include a proportionately large number of artists from Kentucky—a function of experience and access. Having spent years living in Kentucky and working with artists from the immediate region, I have an established network and knowledge base to pull from. The state most heavily represented in the exhibition, however, is Georgia—for reasons that are, perhaps, equally apparent.

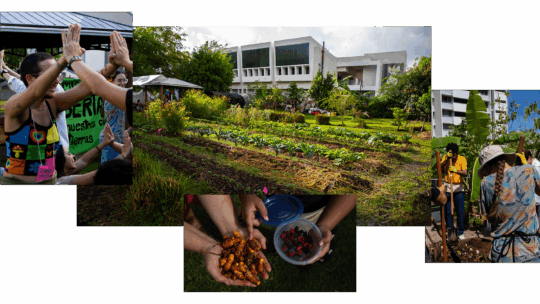

The most obvious influence of Institute 193 on A thousand tomorrows is the inclusion of several artists who have shown there over the past decade. Since 2009, Institute 193 has worked to establish connections between artists from the Southern region and galleries, non-profits, universities, and writers across the United States and beyond. The Atlanta Biennial represents yet another opportunity to advocate for those artists in a very public manner.

LL: Daniel, you presented some footage from the Atlanta-based public-access cable TV show The American Music Show (on air 1985-2005) as part of Atlanta Contemporary’s booth at the 2018 Paris Internationale, and the program is now included in A thousand tomorrows. Can you say more about the show, how you learned of it, and why you’re interested in reexamining its legacy?

DF: I first learned of The American Music Show while doing research on RuPaul’s life here in Atlanta. I’ve always heard stories about how RuPaul would attend most of the openings at Nexus Contemporary. People still speak about his Art Party outfits and how he commanded the room.

In the early 1980s, RuPaul was a huge fan of TAMS and wrote a letter to Dick Richards asking to be featured on the show. In Lettin’ It All Hang Out, his 1995 autobiography, RuPaul allocates a chapter to the show and credits the crew for fostering his creativity and being supportive of his ascension to fame. And, to me, this is part of the glory of TAMS. It was a hodgepodge collective of distinctive creative personalities that made up something special. The show serves as a time capsule from a time when Atlanta was a much, much smaller city. There was a lot more open, cheap space where young creative types could make fun and trouble. This is an Atlanta I want to live in, so I do it vicariously through the show.

A thousand tomorrows, the 2019 Atlanta Biennial co-curated by Daniel Fuller and Phillip March Jones, is on view at Atlanta Contemporary through April 7.