At some point after seeing his 2016 Working Artist Project exhibition BANDIT at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Georgia, I began to think of Atlanta-based artist Craig Drennen as a sort of trickster god, a shape-shifting, rule-breaking, wise and wily figure who’s always a few steps ahead of the rest of us mere mortals. That exhibition, the artist’s first museum solo show, continued his ongoing project centered around Shakespeare’s unfinished play Timon of Athens, for which Drennen develops a distinctive body of work based on each of the characters listed in the play’s dramatis personae. By some miraculous, slightly ironic feat, this potentially narrow approach to art-making has granted Drennen seemingly unfettered freedom, allowing him to playfully invoke painterly techniques ranging from tromp l’oeil to the modernist grid to photorealistic self-portraiture.

Shortly following the closing of his solo show CHIMNEY CANE CANDY HOLE—a continuation of the BANDIT series, which riffs on Santa Claus imagery—at Cloaca Projects in San Francisco, Drennen returned to Atlanta for the opening of Somebody Told Me You People Were Crazy, a group show he curated at Hathaway Gallery, where he is represented in Atlanta. The exhibition takes its name from a line uttered by The Cramps frontman Lux Interior during a 1978 concert by the band at the Napa State Mental Health Hospital in Napa, California. Comparing the performance to exhibiting artwork, Drennen wrote in a curatorial statement, “Every artist can likely empathize with performers delivering their craft under strange conditions to an uncomprehending audience. That might, in fact, be the conditions under which artists most often show their work.”

I spoke with Drennen about curating the exhibition at the gallery in late May, and our conversation has been edited for publication. Drennen teaches at Georgia State University in Atlanta, served for four years as dean of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2018.

Logan Lockner: I don’t want to force any comparisons or contrive patterns I perceive carrying over from your own artistic practice, but I was struck by this conceptual gesture in the curation of this show that’s somewhat like the appropriative gesture that guides your painting practice, where you’re taking an existing cultural phenomenon or moment or product and sort of working in response to it. In this case, of course, that would be the Cramps concert, whereas, in your own work, it’s currently Timon of Athens and was previously Supergirl. Can you say more about that sort of responsive posture?

Craig Drennen: The original idea was for a museum show about artists who I’d always liked and couldn’t understand why they weren’t in the canon, so to speak: people like Eleanor Antin, or Guy de Cointet, and others, of course, all artists I really adore. Then the opportunity came up to curate a show here at Hathaway, and I wondered what could happen if we scaled it down somewhat, if it included people who I’ve had an interest in, people who have been delivering their work in front of an audience that didn’t respond exactly in the right way, at least by my estimation—sort of like The Cramps performing at this mental hospital. People who are committed to the grind are the kind of folks who it’s easy for me to adore.

LL: You’re sort of talking about this idea of cult acclaim—in terms of these artists, and also with The Cramps. You’re someone who, perhaps, has a cult following of your own, in Atlanta and elsewhere.

CD: I would be very terrified to meet any member of that cult! (Laughs)

LL: Can you say more about this sort of liminal position of receiving cult acclaim—achieving a certain level of recognition, but perhaps not in the most conventional sense—and how it relates to certain ideas you’re interested in, such as authority, fame, and history?

CD: Even in our media-saturated, Instagram-saturated time, so much still happens via word-of-mouth. For me, that’s where it started. The first time I saw many of these artists was just because somebody said, “Drennen, you gotta go see this work. Stop what you’re doing, turn the corner, and go to this gallery.” You have that feeling, which I think is a little harder now, of what they used to call the underground. When I first moved to New York, St. Mark’s Books was still on St. Mark’s Street—this was 1992, I think—and I didn’t know it at the time, but all of that was just about to dissolve. That whole world was about to evaporate. It’s a funny thing to witness. I’m not nostalgic for all that; things change, and this is where we are now. But I still think that word of mouth carries a lot of weight.

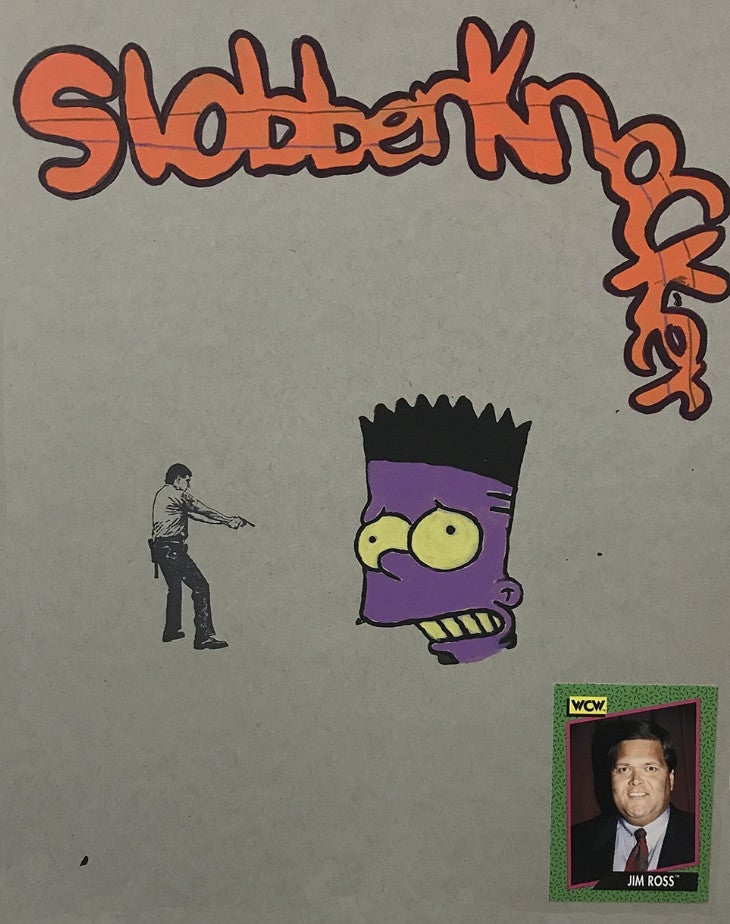

LL: Another factor uniting some of these works is a sense of psychobilly Pop or something like that, a sort of festering sensibility that doesn’t belong to the earlier Pop generation but to this sort of grungier, “I-want-my-MTV” generation of the 1980s or 90s. I see that in Wirth’s paintings but especially in these drawings by David Leggett.

screen print, acrylic on paper, color pencil, and collage on paper, 11 by 14 inches.

CD: I fell in love with Leggett and his work the first time I met him, which was maybe back in 2010. I should’ve done a trade with him years ago. He’s out in LA now. He’s able to convey that complicated emotion of happy-sad, where it’s both hilarious and sad, almost broken but endlessly creative and very fertile and alive.

LL: Many of these artists also share a devotion to craftsmanship, even though they may be working with very different materials. The fact that these works by Jenene Nagy are just graphite and folded paper is incredible.

CD: It’s kind of funny: Jenene and her partner—Joshua West Smith, who’s also in this show—had a gallery in Portland way back in the early 2000s called Tilt, but it was years later before I met them. I remember going to their studio once when she was working on these graphite monochromes, and there were screws poking out the plywood wall she was working on. She was doing rubbings right on top of the screw heads! People who are attracted to monochromes are usually fastidious beyond all measure, but these screw heads would be showing up in Jenene’s rubbings, and I would be like, “What about that?” And she would say, “Ah, it’s okay.” I remember being amazed by that ability to allow impurity.

LL: There’s a nice visual interplay between Nagy’s monochromes and these works by Christopher Carroll.

CD: How many folks do you know who are super dedicated to fresco? He’s immersed in it! He uses holy water to mix the plaster for these frescoes. He was recently in a traveling museum show about art and the occult. Around the edges of each fresco, there’s text in an arcane language from a witchcraft society. The images in all of the frescoes are forest scenes from the pagan woods, and in the video he’s giving himself and a tree the same tattoo, sort of as a blood brother ritual.

The role of text became an unexpectedly interesting component of the show: Leggett is using it, Carroll is using it, the Colleen Asper video is entirely text-typing.

LL: For the Asper video and Carroll’s occult language, the text is emphasized strongly but also completely indecipherable.

CD: Exactly. Knowable and unknowable at the same time.

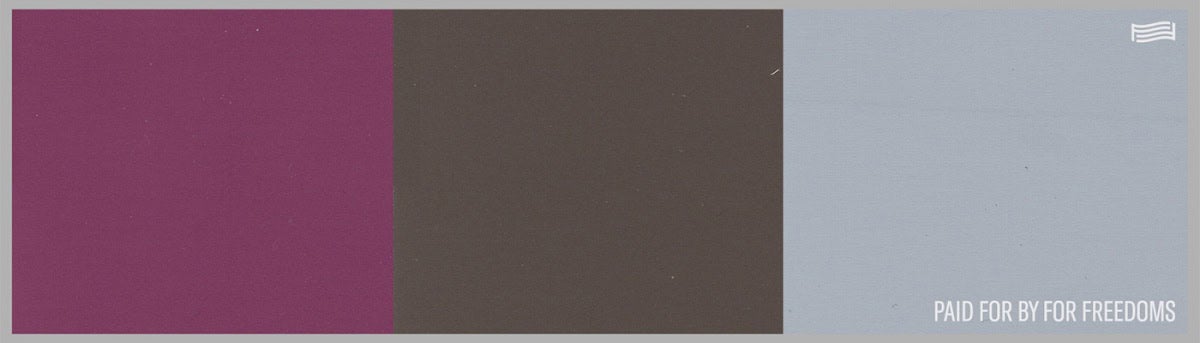

LL: (Gesturing to Steve Locke’s wall drawing Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie) This artist, Steve Locke, is based in Boston, right?

CD: Not for very much longer—he’s just accepted a teaching position at Pratt, so we caught him en route to New York. I would like to not bother an artist during that sort of transition, but he said yes to my invitation right away. I sent him images of that wall, and he sent us plans and approved the installation.

He had exhibited a fabric version of this piece, Three Deliberate Grays for Freddie, at the Gardner Museum in Boston, and it was just unbelievably gorgeous: tragic and formal and sad. I got to New York right when the Félix González-Torres exhibition was happening at the Guggenheim, and I remember being devastated by how what seems like reductive formalism could carry so much emotional content. The three stripes in Locke’s piece are the color averages from these three photos of Freddie Gray, who, as you know, was killed in the back of a police van in Baltimore.

Steve is fearless as an artist and as a human being. He always goes to that trauma point and manages to find a way to say something new or see it from an angle nobody else has come up with. He’s a great painter too—his show at the ICA in Boston a few years back was full of gorgeous, saturated paintings. He’s agile in all those traditions simultaneously.

LL: I don’t know if it’s a backhanded compliment or what, but there’s some wry joke in naming a show Somebody Told Me You People Were Crazy—perhaps especially when some of these artists haven’t shown in Atlanta before and may be encountering this audience for the first time.

CD: (Laughs) I think in the original Cramps performance, Lux Interior was being serious. He said, “Somebody told me you people were crazy,” but it’s like, you look alright, you’re fine. Maybe it’s a comment of reconciliation. Like, “I don’t care what anybody said, I like you guys.”

Curated by Craig Drennen and featuring work by artists Colleen Asper, Marc Brotherton, Christopher Carroll, Mel Cook, David Leggett, Steve Locke, Jenene Nagy, Joshua West Smith, and Tim Wirth, Somebody Told Me You People Were Crazy is on view at Hathaway in Atlanta through July 13. Drennen will give a curator talk at the gallery on Wednesday, June 12.