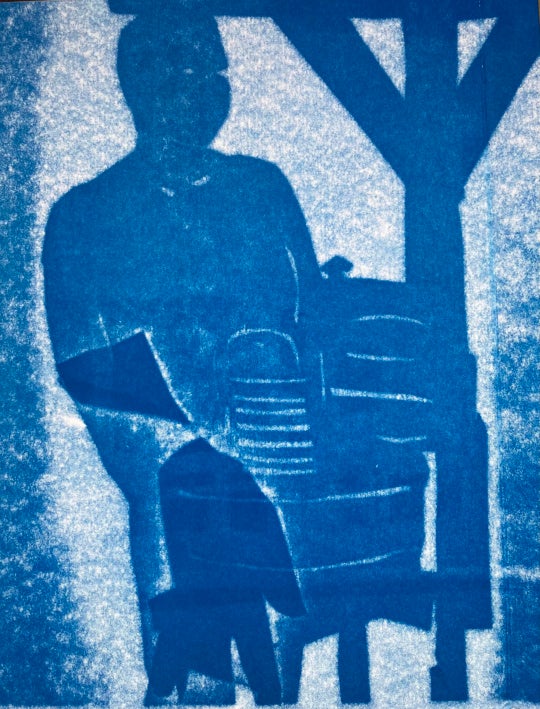

This week marks one year since I first saw the work of Jamaican-born artist Cosmo Whyte in the exhibition Rites at the Zuckerman Museum of Art. Curated by artist Fahamu Pecou, Rites was a small group show featuring work dealing with race, gender, and growing up as a Black man. I was mesmerized by Whyte’s immense charcoal drawings, which depict the fractured trajectories of figures in motion, such as the young Black boys breakdancing in Sweet, sweet, Back.Whyte lived in Atlanta from 2008 until 2012 before relocating to Michigan to pursue his MFA, and he returned to the city after graduating in 2015. He recently gained gallery representation in Atlanta with Marcia Wood Gallery, and this year his work has been included in exhibitions at the National Gallery of Jamaica in Kingston, the Punkt Ø Galleri F 15 in Moss, Norway, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. At the Mana Contemporary in Newark, New Jersey, a recently closed group exhibition presented by the International Sculpture Center borrowed its name from Whyte’s installation Wake the Town and Tell the People.

When the artists selected to participate in the Atlanta Biennial (ATLBNL) were announced earlier this summer, Whyte’s name immediately caught my attention. In anticipation of the biennial’s opening this weekend, I visited his studio, which is located in a repurposed church building near Morehouse College, where he has taught since last year. “I’m used to artists’ studios being located in repurposed buildings,” I tell him as he guides me through the hallways, “but not in churches.” When we entered his studio, I found drawings similar to the ones I’d seen in Rites fastened to the walls.

Logan Lockner: I’m glad to see these charcoal drawings, because my introduction to your work was the drawings in Rites at the Zuckerman—I especially loved Sweet, sweet, Back. Is drawing where your practice originated?

Cosmo Whyte: Yeah, and even as I branch out into other mediums, drawing is always the pillar of my practice.

LL: Are these drawings part of a series?

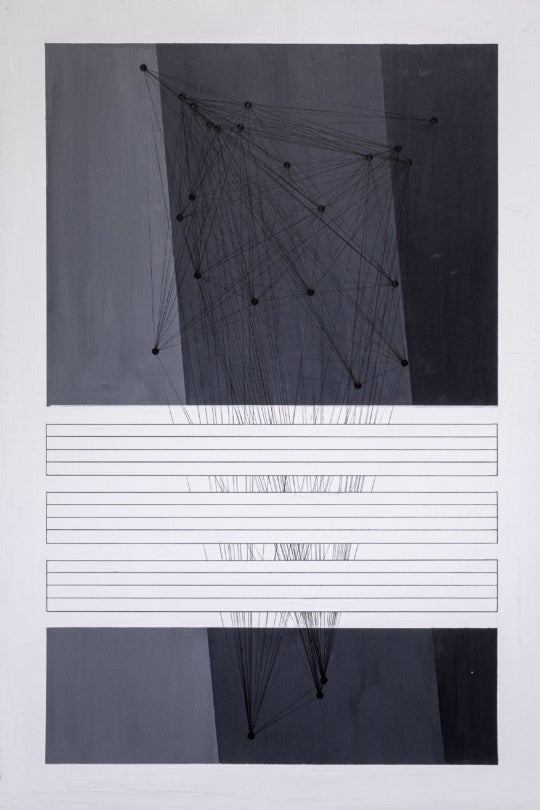

CW: It’s the early stages of a series. I feel there are two things going on in these drawings, and I’ll work on them concurrently and then see where they merge later on. My entire body of work deals with migration in some way or form, and I was just trying to find a new way of talking about migration that went beyond catchphrases like “diaspora” or “identity in flux.” I was trying to find a new way to talk about it, if only for myself, to keep it fresh and exciting. As I was going through some of my old college notes, I came across the term “colonial botany.” I’m fascinated by this notion of plants that have been uprooted and deposited in other places in the world; they can mimic the movement of human bodies. These drawings are my first attempt to grapple with that idea.

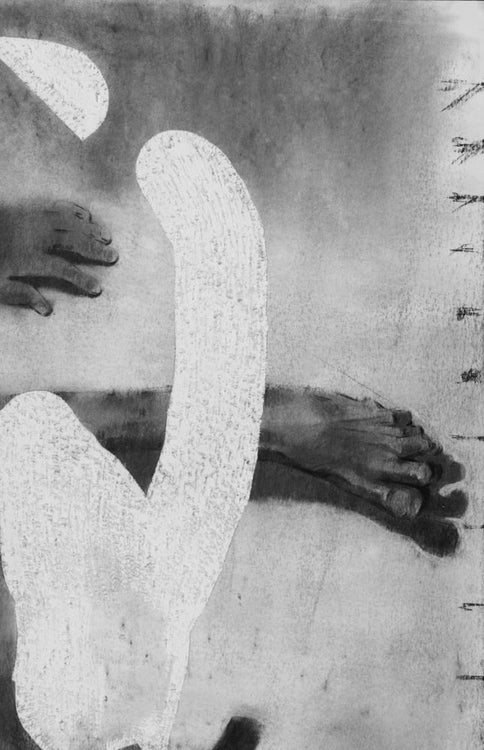

LL: I recognize this fraying of the paper! I saw the show at the Zuckerman twice before I realized what it was — at first I thought it was thick layers of paint. And here is gold leaf again as well. How did you decide to incorporate these elements into your work?

CW: The fraying of the paper came about through experimentation in grad school. I’ve always been interested in repetition and erasure, so my drawing utensils are literally a stick of charcoal and an eraser, and I use that to get the variations in tone. Also, I always work on really thick paper because I abuse the paper a lot. I’ll use an electric sander to knock things back. I approach drawings in layers, like paintings. In grad school I decided why not take this erasure one step further and scrape away at the paper? I liked what it produced. I refer to them as “keloids.”

LL: Like the scar…

CW: Yeah, a little bit of scar tissue. I think of it as the body registering an event, without me saying if it was a traumatic event or not, so it’s just registering a mark in history. The gold leaf was in previous drawings a couple of years back that I was doing on clayboard. I view this as an evolution of that. I started to combine the two with this piece Golden Kicks.

LL: You just got back from a residency at Elsewhere in North Carolina, right? How was that?

CW: Definitely a new experience. I’ve never been at a residency quite like that one before, where you were required to use the materials that are there. It’s quite overwhelming at first. There’s just so much stuff. You have to sort through it and also make it not feel too tangential to the work that you’re doing in your own personal studio.

LL: Did you feel constricted by that?

CW: No, I didn’t. I ended up doing a piece using their hospitality equipment — all the dishes and the plates — so my piece is located in the kitchen. For that work, texts that I was reading prior to Elsewhere sort of spilled over into the residency. I was reading Of Hospitality by Derrida and thinking about what it means to welcome the sometimes unwanted guest, and about this heated election where there’s been so much rhetoric about keeping people out. What does it mean to be hospitable in a country that’s built on migration?

LL: Is that something that happens often, where what you’re reading affects the work you’re making? Or is it a more mutually informed process?

CW: It’s mutually informed—I had a professor in grad school who always said, “We’re not making work based on readings.” The reading is supposed to inform, almost like a silent partner to the work. One doesn’t need to have read the Derrida to understand the piece, or you can’t look at the piece and immediately say, “Ah, Derrida!”

LL: Right. That would be too easy and didactic. What is the piece like?

CW: It is a cabinet filled with all the dishware, and there is a deconstructed speaker attached to one side of it. The rumble from the speaker shakes the dishware, and the guest is allowed to regulate the volume, so they could potentially break all the dishes if they wanted to. And then etched into the glass is a text that comes from the readings, of Derrida responding to an aborigine custom in which the women weep whenever a new guest arrives, because the old version of yourself dies as you allow yourself to be changed by a foreigner or a stranger.

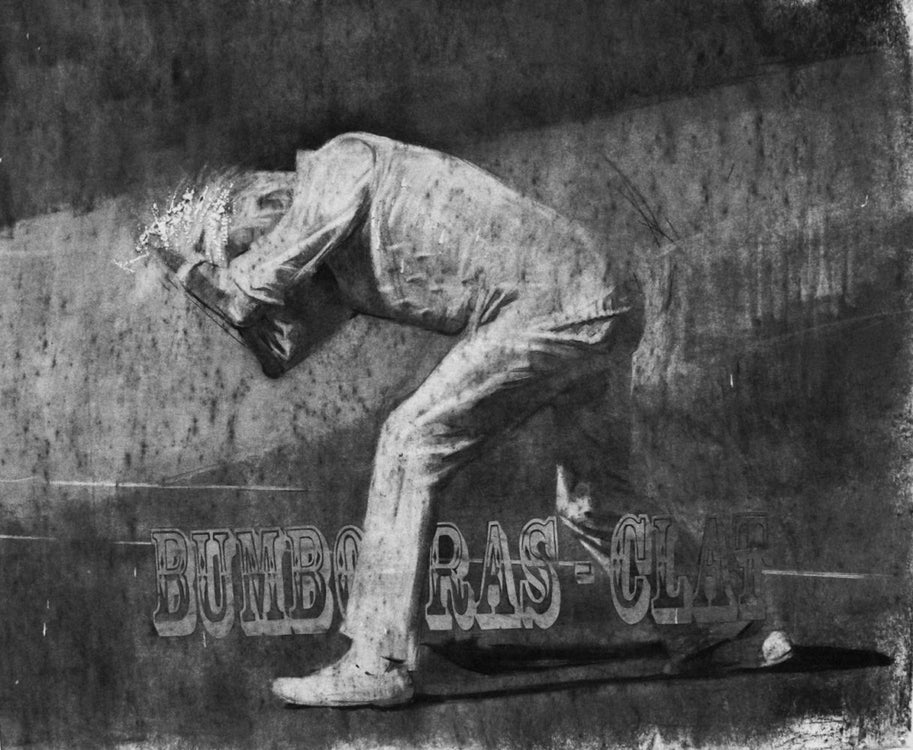

LL: Have you used text in your work before?

CW: I have. We can pull out a drawing here … I went through archival images of, for instance, West Indies cricket teams playing England, and cricket is one of those colonial retentions that the Caribbean was able to use as an anti-colonial movement. So in this particular drawing, you see a figure clad in all white, the traditional cricket uniform, and they’re cowering as though they’ve just been hit by the ball. But then written [between the figure’s legs] is a Jamaican curse word, which is in our Creole dialect, Patois. I was trying to work with the juxtaposition of a Creole language that was created out of the clash of cultures through colonialism and the colonial sport which is the epitome of well-spoken English and gentlemanliness. That was one of the first examples of text, and it’s also the first time I started scraping the paper.

LL: How did you find out you were selected to participate in the Atlanta Biennial opening this weekend?

CW: I had a studio visit with Victoria Camblin. My impression was just that she wanted to meet me and see the work, and we had a great conversation and I really enjoyed the visit. And then it may have been a couple of days later that it was announced that there was going to be this Atlanta Biennial and that she was one of the curators, and then a few days afterwards she contacted me.

LL: You’re one of the four Atlanta artists in the biennial, and the rest of were chosen from across the South. How do you feel your work is connected to living in Atlanta and the South?

CW: What I find interesting about my participation in the show is how my own migration from a place even further south than Atlanta fits in. I was joking and said I moved from the south to the South. [laughs] And then there’s the fact that there are so many West Indians, particularly Jamaicans, on the outskirts of the city. That’s something I’ve been actively thinking about. It hasn’t quite manifested itself in the works that you see here, but it’s something I’m writing about and documenting in my sketchbooks—the changing demographics of Atlanta, beyond the binary of Black and white. As a welcoming city, Atlanta has a higher growth rate of immigrants than a place like New York, which is crazy. How will that look a couple of years from now? And coming back to the Derrida article on hospitality, how is Atlanta preparing itself or not preparing itself to be changed by the influx of people from other places?

LL: Exactly, which is especially ironic given stereotypes about Southern hospitality. Can you talk a little bit about the work you’ve done for the biennial?

CW: The work for the biennial is a piece I’ve shown before; part of it was in the Norway show. But this is the first time I feel like I’m putting all of the elements together to make it how I wanted it. That’s not to say I don’t like how it was in Norway, but there were various elements I had working with other pieces that I felt finally synergized to create this. I almost view it as a new piece.

LL: Are there any other artists included in ATLBNL whose work you’re especially excited to see?

CW: Yes, there’s Stacy Lynn Waddell. I’m really excited to see her work and meet her in person. And there’s Tommy Coleman, he’s from Florida. I’m also very excited about Coco Fusco, Sharon Norwood, and Christina West.

LL: Do you have any rituals or habits when you’re working in the studio?

CW: I think one of the biggest rituals I have is in preparation to get to the studio. A lot of times I just walk from Morehouse, and I really enjoy that time because it allows me to start thinking about what I’m doing that day but also the work in a broader context, or larger projects. I’m always thinking of a show. It’s rarely with a specific space in mind, but I always think, once I’ve created this piece, what is the next piece that’s going to be in relation to it? How are they talking to each other? Where does this need to go? I also don’t feel that one piece should provide all the answers to a particular question; it should build upon the question so that by the end of the show you have a larger idea.