Trash (Process Theatre Company), the most recent play written by Johnny Drago, is a comical and dramatic look into the home of Jinx Malibu, a fictive former D-list celebrity best known for her Rocket Pussy movies and television commercials for diet pills.

Living together in a small home, Jinx, her children Loogie (Geoff “Googie” Uterhardt) and Smudge (Amanda Cucher), and her mother, lovingly referred to as Othermama (Jo Howarth), are isolated in many ways. Smudge, the teenage daughter, doesn’t know how old she is and has never been outdoors. They do not have a phone or computer, and when an uninvited stranger (Daniel Pino) arrives, the kids are sent into a panic by the sound of the doorbell. The stranger is a celebrity blogger from Hollywood—and thus nicknamed “Mr. Hollywood” by the family—who has come to give fans an update on Jinx’s decline. Blinded by the delusion of a possible career revival, Jinx mistakes the blogger’s intentions and insists on meeting with him to discuss her future.

Drago’s background in theater and literature influenced the characters he created for Trash. The plot, as Drago states, is loosely based on Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie. Flannery O’Connor’s short story “Good Country People” also served as an inspiration for the roles of Smudge and Mr. Hollywood.

Reality television programs such as Hoarders and The Anna Nicole Show also influenced the play. Although lacking the cultivation of classic literature, such media can show the dark and melodramatic side of human behavior, which is something Drago does not shy away from. While Trash is full of comedic moments, the plot takes an unexpected turn and exposes the audience to the sad, disturbing history of the characters’ personal relationships.

In the last year Drago was named one of three Leap Year artists and was a recipient of the Emerging Artist Award for the Literary Arts; his play Kiss of the Vampire was named “Best Original Work” by the Metropolitan Atlanta Theater. He was kind enough to meet with me and answer a few questions about the creation of Trash, what inspired him, and how he developed the play’s characters.

Scott Daughtridge: How did your participation in Leap Year impact your completion of the script for Trash?

Johnny Drago: I think I was already supposed to do Trash before the year started. I knew I was doing a play for Process Theatre because I had already done one years ago for them called Kiss of the Vampire, a romantic comedy about vampires—just before the trend.

This was the first time that I wrote [a play] knowing who the actors were. I specifically wrote everything for those guys, and I did an early draft when [my] Leap Year first started, and [I] kept refining it and refining it through the course of the year.

SD: How did [director] Topher Payne and the cast impact the transition of the written play to the onstage production?

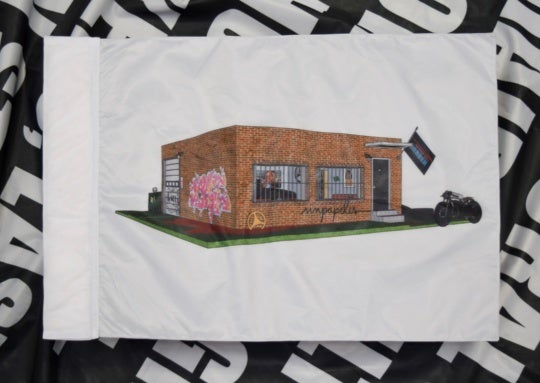

JD: I wrote the play and we had done some private readings and worked on it, then I went away to Hambidge [Center for the Creative Arts & Sciences] for two weeks [as] they started rehearsal, and when I came back they had just built and built and built so much. They’re so creative, all of them. I feel like I built a blueprint for a playground. Topher built that whole set, and the actors have just climbed all over those monkey bars.

I watch it and I love the production so much. Everybody’s contributed so much, and I really feel like it’s a group effort. I think you can really see that, especially in the set design. They just fully inhabit that space and tear apart that stuff. I couldn’t even have pictured it.

SD: How long did it take Topher [in his role as set designer] to collect that much trash?

JD: The actors were literally bringing in their own garbage from home. It was literally bring your garbage to work day. Then they had to wash everything to keep away the bugs! Topher was really invested in the idea that, because the set was kind of dangerous and unpredictable, he wanted to know where everything was. He spent days and days and weeks and hours placing everything and really thinking everything out to keep things safe for the actors, and thinking out where props needed to be, and where everyone would be placed at any moment.

SD: Did you intend for the actor playing Jinx Malibu to be a male, or did you audition various people? What about casting the other roles?

JD: What I really wanted to do was pick the people I wanted to work with—actors I really admire—and write great roles for them. DeWayne Morgan, the actor who played Jinx, is the artistic director of Process Theatre, so he kind of runs that show. I had worked with him in Designing Women Live, which is very performative, and working with DeWayne and knowing DeWayne and knowing what a fine actor he is and the emotional depths that he has, I knew I wanted to write a big, sloppy, messy, rag role for him to just stand front and center and own. Designing Women Live is all jokes—light, sitcom-style comedy—but what I wanted to access was both sides of what I knew he could do, which is hilarious physical and verbal comedy, drag comedy, but then also this emotional depth and devastation and darkness.

Amanda [Cucher] also—who plays Smudge, the daughter—she’s just a great, great, great underutilized actress in this town, and the speech that she has about looking into space, I really wrote that with her voice in mind and she just nailed it. All the actors were that way.

The only [role] I didn’t already know [what actor] I was writing for was Mr. Hollywood, but I think that works because he’s the interloper, because he comes from somewhere else and doesn’t talk like them, and he’s a stranger. I was fine with letting that actor and that character be a stranger to me, too.

SD: Were you watching anything, TV or movies, to inspire the play?

JD: I watched the Anna Nicole Show when it was on TV and was obsessed with it at the time. Her story is so sad. It’s an example of fans and America and consumers devouring a celebrity. What I watched more of were Anna Nicole’s action movies. I think one is called Skyscraper, and it’s just atrocious.

What I wanted to do with Jinx was to present her like a cartoon, like she’s a big joke. Throughout the play she keeps saying things like, “I’m a real person now with real feelings. I’m not just some big joke.” In the second act it turns super-dark, and my intention was that everything starts off like a cartoon and then by the end of the play you’re seeing real relationships and real people. There’s a moment at the end, after everything has happened—and this was Topher putting a beautiful directorial touch on it—where Loogie and Othermama don’t know exactly what to do, and they don’t know how to relate, and she kind of reaches out to him and he kind of reaches out to her, but they don’t, they can’t connect in that way. And to me that is such a beautiful and real moment.

SD: The word “faggot” is used in a comical way in the play, and it drew big laughs from the audience. Can you talk about how you view that word and the role you intended it to have in Trash?

JD: I think in some ways it’s related to the idea that this family is so isolated that they have almost evolved their own language and how they describe things and refer to the world. They’re so trapped in their own world that they have a secret language, and so when they say “faggot” they don’t even think that it means anything. Smudge doesn’t know that it means anything.

I saw some mixed responses. I saw some people get uncomfortable when [the actors] said it. The first time it comes up, [the actors] really have at it and I saw some people bristle and not go along for the ride, and it’s such a roller coaster you have to submit your will to this insane journey.

SD: At one point Jinx looks at the audience and says, “I wish there was a faggot here to watch me die.” Did you intend for that to be directed to any audience members that were gay?

JD: No, I’m not calling anyone in the audience in a faggot. There used to be a gay theater company in town that was disbanding right when I first moved here, about 10 years ago. Process Theatre Company has really stepped in and filled the void. They do a lot of specifically gay work. I know they’re kind of the gay de facto theater in this town. But it’s also my attempt to neutralize the word in some way, by making it something that’s laughable. There is something that’s so powerful, immediate, and dangerous about that word, so I guess if I treat it as [casually] or uncautiously as possible it takes away some of that.