Mike Schreiber has photographed some big names in hip-hop music, but he doesn’t get caught up in the glitz and glam. His latest exhibition opens at Hagedorn Foundation Gallery on Saturday, July 9, 2011, as part of the National Black Arts Festival (NBAF). Since publishing his book, Schreiber has received a lot of attention from both the art and music worlds, but the name of Schreiber’s exhibition and book, True Hip-Hop, has more to do with his belief that photography should be honest, rather than any specific statement about hip-hop culture. Over the phone, Schreiber made sure to stress that, at the heart of his work, he’s a documentary photographer who finds inspiration from people with big personalities—hip-hop artist or not.

Schreiber studied anthropology at the University of Connecticut. There is no doubt that his background in anthropology influenced his documentary style. During our interview, Schreiber explained that anthropology was just a way to look critically at the world. Through his lens, Schreiber attempts to make his photographs as real as possible. Of course, the irony is that most of these images were shot for magazine spreads—the most unnatural settings. Schreiber began photographing hip-hop musicians because their shows were the easiest to gain access to in the 1990s. The subculture became his project for twelve years, and his photographs graced the pages of magazines such as VIBE, The Source, and Rolling Stone.

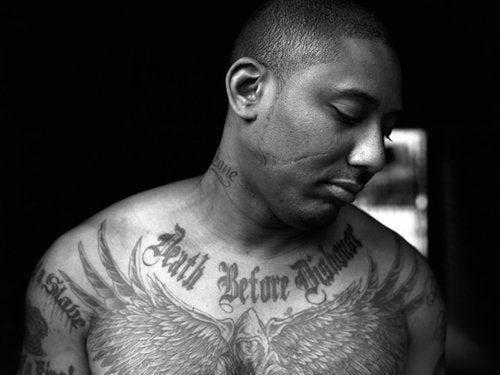

According to Brenda Massie, director of Hagedorn Foundation Gallery, what’s compelling about Schreiber’s work is both the softness and hardness of his images. Hip-hop performers have an edginess and toughness about them. Look at Maino as an example. He was convicted of drug-related kidnapping and served ten years in prison. The large portrait of Maino on display in the gallery, however, shows a softer side, vulnerability even, not often found in music videos and glossy magazines.

This is Hagedorn’s third year working with the National Black Arts Festival. In years past, they have brought such artists as Malick Sidibe, Dawoud Bey, Demetrius Oliver, J.D. Okhai Ojeikere, and LaToya Ruby Frazier to Atlanta. Massie said the partnership between Hagedorn and NBAF is important because “artists and the arts are fundamental to change in this country.” “The arts provide an attitude adjustment … over time,” she added. “We are all ready for everyone to work together to make this a better nation. We can only do it by recognizing and celebrating everyone’s contribution to our world.” These are lofty statements to make in Atlanta considering its checkered past in racial relations, a history that continues today with the immigration bill, HB 87, that Governor Deal signed into law this year.

The theme of this year’s NBAF is “Unexpected Encounters,” and Massie explains that Schreiber’s gift is capturing his subjects, not in the glamour of a performance, but “in their own personal moments.” In the celebrity culture we all live in today, it’s easy to get caught up in the hype. But Schreiber captures intimate moments that we wouldn’t expect from famous hip-hop artists who usually present themselves as jaded and tough. Schreiber gives us a different view of people we read about in the press and hear on the radio. Although I’m not sure his images will change attitudes (perhaps I’m too pessimistic), I know his images document a softer side of a culture with a lot of anger towards its history of oppression and racism.

Photography, not hip-hop, is Schreiber’s true interest. Both subjects have one thing in common: hustling. In the book, Schreiber describes a photo shoot for The Source. He was assigned to shoot Mos Def and Talib Kweli at Nkiru Books, their recently purchased bookstore in Brooklyn that now operates as the Nkiru Center for Education and Culture. He took some pictures of the building, and waited hours and hours for the two to show up. Had his ego or impatience gotten the best of him, he never would have taken one of his most famous images of Mos Def. Individual portraits were not part of the assignment, but as Schreiber wrote in his book, “Nobody was really giving me assignments to shoot portraits at the time, so I really needed to take what was in front of me and get the most out of every opportunity.” This attitude is part of why he’s succeeded in getting to this point in his career.

The exhibition at Hagedorn includes a majority of 16-x-20-inch portraits and a few eye-catching 40-x-50-inch prints. After becoming familiar with Schreiber’s images first through his book, seeing the images printed so large leaves a lasting impression. They are simply striking. The book, on the other hand, shines because of the stories that accompany the images. The idea for the book came about from a show at Mighty Tanaka in Brooklyn, where the gallerists enjoyed hearing tales from Schreiber’s career. Humorous and personal, they often give a greater glimpse into the world of the artist than his subjects. The combination of the sizes of prints on display and the intimacy of the book allow for different levels of exploring Schreiber’s work.

In staying true to his self, Schreiber rarely shoots with a digital camera. He doesn’t believe that technology should dictate the process, asking, “You can paint on the computer, but does that mean you shouldn’t paint with oils anymore?” He’s watched great photographers switch to the digital realm and second-guess themselves, always looking down at the result on the screen. He doesn’t want to be like that, adding that there is still something fun about getting back the contact sheets.

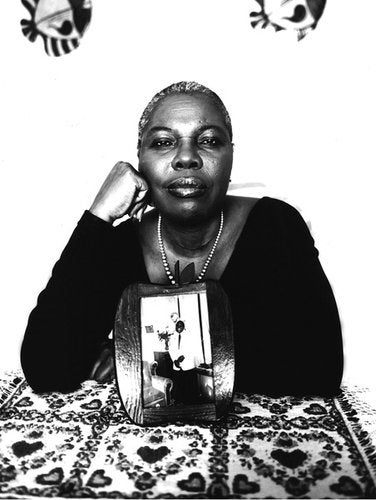

The image of Voletta Wallace is one of Schreiber’s favorites, and it is an example of his work at its best. In the image, Wallace is sitting at a table staring directly into the lens. In front of her is a framed picture of her son, the Notorious B.I.G., as a teenager. The rapper was killed in a drive-by shooting in 1997 in Los Angeles, and Schreiber was sent by XXL magazine to shoot her portrait. The Notorious B.I.G. still is a big name in rap music, and he has been placed on a pedestal by his fans, perhaps even more since his death. It struck Schreiber that “she diapered him.” In his book, Schreiber says, “It made me sad that the only reason I was taking her picture was because her son had been murdered.” To Voletta Wallace, this famous rapper was her son who was killed in a tragedy. At the end of the day, everyone is someone’s son or daughter regardless of the albums they’ve sold or the awards they’ve won. What strikes me most about this photo is the image of the rapper: a young, smiling boy. The honesty of this photograph, and others like it, are what makes Schreiber great.

In talking with him, I can see why he has the ability to capture these intimate portraits. He’s humble and doesn’t take himself too seriously. He has a wonderful sense of humor that also translates to his photographs. He said he admired the work of Elliott Erwitt, because it showed him that photography can be fun and lighthearted. Massie described Schreiber as a “chameleon,” getting close to his subjects and gaining their admiration and respect. These are all qualities that good documentary photographers share.

Since the release of the book, Schreiber has had exhibitions all over the world. What’s next? Schreiber has images from a trip to Ghana in 2009 that he hasn’t released yet, and he wants to do something special with them. After the show at Hagedorn, Schreiber plans to pick up the camera again, take a trip, and do something fun. Creative types have to keep moving, and evolving, which is exactly what he plans to do.

The exhibition, True Hip-Hop, opens at Hagedorn Foundation Gallery on Saturday, July 9, 2011, with a panel discussion at 5:00 p.m. featuring Mike Schreiber, Dr. Joyce Wilson of Morehouse College, Atlanta-based artist Fahamu Pecou, and Rodney Carmichael of Creative Loafing newspaper, followed by a book signing and reception.