A decade ago, Brian Hitselberger and Jessica Wohl met in Athens when they entered the MFA program in painting and drawing at the University of Georgia. For the next three years, they studied alongside one another, occasionally collaborating and significantly developing their individual studio practices. Following graduate school, the artists, both of whom now work as educators — Hitselberger at Piedmont College and Wohl at Sewanee, the University of the South — have maintained an ongoing friendship and dialogue on art, teaching, and, most recently family life. Hitselberger creates paintings and works on paper, as well as wall-based installations that draw on his background in printmaking. Wohl creates drawings and mixed-media pieces incorporating photography, collage, embroidery, and soft sculpture.

During the months of October and November of 2016, they both had solo exhibitions at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. The pairing revealed a surprising overlap between their work in regard to imagery, technique, and subject matter explored independently by each of them. The following conversation was conducted via email over several weeks as the artists explored how a single image might yield multiple meanings for different artists and how diverging creative intentions—particularly those of friends, family members, studio mates, teachers, students, and partners—can occasionally yield similar results.

Brian Hitselberger : For ten years now we’ve watched each other’s work evolve quite a bit. What’s so interesting to me is that we seem to be in similar territories right now, having arrived there for very different reasons. Maybe a good place to start would be for us to both discuss how the types of imagery and techniques that have overlapped relate individually to our individual studio practices. I’m speaking specifically of your most recent show “Love Thy Neighbor” and my last show “Seeing in the Dark.” How did you arrive at the work that composed your show, conceptually and formally?

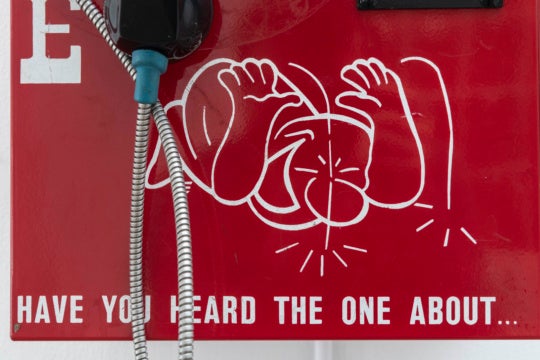

Jessica Wohl: I needed to respond to the world around me, as opposed to continuing an investigation into my own psyche. I conceived of these works during the years when we saw increasing gun violence, police brutality, and people of color being killed unjustly. I felt a need to create works that could offer comfort to those in pain and to those whose anger, frustration, and sense of hopelessness might be soothed by something warm and intimate. In addition, I started to see how polarized our country was becoming in regard to these socio-political issues, and I felt that if we could somehow conquer physical and psychological barriers, we perhaps might be able to come together and move forward.

With that in mind, I made sure that the quilts presented a barrier that keeps the viewer from something lovelier beyond their reach, and that these measures of separation are abstractions of fences, gates, walls, prison bars, etc. — devices that are designed to keep one group of people from another.

My drawing series Resting in Peace is slightly different. It’s designed to highlight the moments when all of us are the same, either in slumber or in death. It’s a piece that presents people of varying ages, sexes, and colors as equals. All drawn with the same scale and with the same materials, it strips the group of any hierarchy and highlights our differences and similarities. It also depicts a state where, devoid of conscious thoughts, the subjects are merely at peace, together.

Depicting sleeping subjects is rather new for me, but investigating associations with the bed is not. I have exploited the bed as a domestic place that is imbued with the energetic residue of those who’ve slept in it. Brian, you and I also collaborated on Stitched, our performance at ATHICA where we were sewn into a bed together. I wonder if you might share a little bit about the role sleep has played in your work over time. Where did your interest in sleep come from, and how has it evolved?

Brian: Sleep and the act of sleeping emerged as subject matter for me as a way to examine the nature of thought itself, as well as the event of thinking. I had been reading a lot of Freud and Jonathan Lear’s reworkings of Freud’s ideas and became interested in the kinds of restlessness of mind and associative connections that happen in dreaming and sleep states. These investigations are psychoanalytic in nature, which is one form of knowledge. From a scientific standpoint, we really don’t know too much about sleep. Additionally, I’m interested in the idea of variation within repetition– and sleep is of course a perfect example of this. No two experiences of sleep are ever the same, yet it is an experience that is shared by all persons. That connection intrigued me.

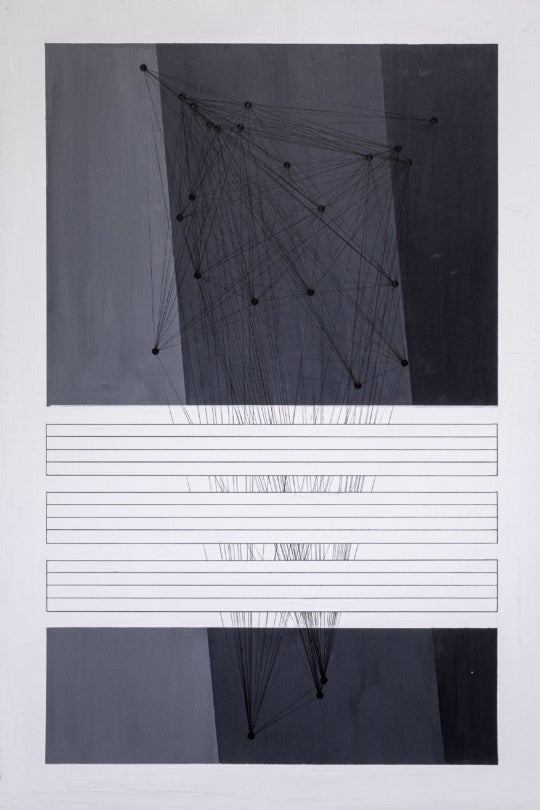

At first, I approached sleep as a site of exploration, thinking of it as a potential space where ideas are formed. I was initially interested in hypnogogic and hypnopompic states—the precise moment of falling asleep or of waking up, respectively—as these seem to represent a joining in time of two distinct states of consciousness and the types of worlds they inhabit or create. I created a large wall work, Self-Portrait In and Out of Sleep, that attempted to depict one of these moments while simultaneously creating a field that would visually envelop the viewer with its scale. Subsequent works were drawn directly on the wall, in order to create ephemerality that further described the types of consciousness I was exploring. Additionally, I started to treat the work as an opportunity to depict the sleeper as well as the dream at the same time and in the same space. This was directly informed by Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters from his seminal etching series Los Caprichos, a work that I’ve admired forever and would see regularly, as Tulane (my undergraduate college) had a copy in its permanent collection.

To me, Jessica, it sounds like you’ve used the image of a sleeper in your work as a way to depict individuals without hierarchy, and equally vulnerable – a kind of inarguable fact that is at odds with what we perceive in our contemporary waking life. In my work, depicting sleepers was a way to, in a sense, begin exploring differences between people, but within an experience that is shared. Is that fair to say?

Jessica: Yes, I think that’s a very poetic way of approaching what is more and more becoming a very charged and polarizing topic of conversation– namely, that we are facing a national crisis where differences between people are being magnified by one group, while other groups try to minimize them or at least embrace those differences as valuable and vital components of our society. It took me years to start addressing these issues in my work, because I spent the majority of the last 10 years using my practice to work through my own issues.

I know the work you made was also biographical in many ways, however subtle. It seems now that you too are beginning to look outward to more social issues as sources of inspiration, such as exploring the differences and shared experiences between people. What changed for you?

Brian: I think it’s just a natural extension of getting older and having had more experiences. But it is also seeing oneself as a part of the world instead of opposed to it. What once felt so individual or isolating becomes contextualized within a larger reality.

For example, when I reflect on my experience of growing up gay in the Southern United States, I see it less and less as my own personal story of struggle, and more as an identification with a larger community. There’s a complex story of Southern queerness, and it’s not a story that’s exclusively my own. My recent work has been a way of seeking or highlighting connectedness between shared experiences, even as those experiences remain mysterious to the people they are happening to.

And of course, becoming part of a family represented another enormous shift for me; all of a sudden, your life is intertwined with other people in a very direct way, some of whom are children and are being formed directly by you. You understand that you move through the world with other people, not as a solo agent. It’s incredibly humbling, and gets you out of your own head.

This is a complex question to answer simply, because I don’t want to imply that personal, autobiographical work isn’t valid or necessary – or something exclusively relegated to younger artists who are somehow less experienced and more egocentric. It is quite the opposite, in fact – I believe it’s possible to make a work that speaks so precisely about your own experience that it opens up and becomes universal. I’m thinking of work like Nan Goldin’s Ballad of Sexual Dependency or Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, to cite two examples from what could be an endless list. These are explicitly personal works that speak to larger realities. And in a way, this is something I’m aspiring to do as well, albeit through different means. My experience, my direct lived experience, is always the starting point for my work – although it may not be a destination. Thoughts about family, inquiries about sleep…. thinking through one’s role within the world – these are the ideas that take form in my studio. What may culminate as a poetic or abstract work could begin as a series of sleepless nights that I myself experience. One of my goals is to render specificity into abstraction.

I’m sure you have a few things to say about this too! And then we should talk quilts.

Jessica: I know what you mean. Entering into a marriage, gaining a new family, and having a child have profoundly changed my practice as well. Before I was married, much of my work explored anxieties and fears that I would never find a partner and find that “Happily Ever After.” Growing up a child of divorce, among many other family members besides my parents who were on second marriages, the reality of a lifelong marriage and the attainment of the American Dream seemed elusive to me, at best. When I had worked through those issues both in and out of the studio and had found a partner, it was amazing how quickly my work became inspired by the world we would face together rather than the fears of what I might have encountered alone. It became abundantly clear that my work would have to address the issues that would affect my family, issues that forced me to recognize how skewed and naive my own upbringing had been. It really was a true awakening that happened over the course of four years, in conjunction with insurmountable insensitivity, gun violence, greed, police brutality, and political polarization happening in the world around us.

At that time, I needed to turn my attention toward healing. Turning on the news made me want to cocoon myself in a blanket of protection, and I actually feared for my family’s lives in ways I never did before. Works like Mike Kelley’s More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid were particularly influential for their use of “imbued love” as a medium, in lieu of paint. Wanting to rely on the sense of touch to ignite healing and connection, like Kelley, I could harness the energetic residue left in a found (and discarded) object to conjure up the shared experience of comforting one’s self. In the studio, I turned to quilts to provide that comfort and protection, to self-soothe, to provide something soft and warm— something that I could touch and hold in my hands that could bring people together. In addition, by making quilts exclusively out of used, domestic textiles found at thrift stores and yard sales, I could literally bring the worn and used ephemera of people across this country together into something that could be both critical of our country and provide its citizens respite from anger hopelessness and despair.

Brian, you’ve just begun to reference quilts in your work as well, through you’re using painted imagery instead of fabric. I laughed to myself when I first saw this, not surprised at all that we once again had independently arrived at similar themes. How did you come to use quiltlike imagery in your paintings? It seems to me that in some cases, you’ve almost opened them up to reveal deep spaces, where the night sky is both a part of the quilt and indicative of a space beyond it.

Brian: That’s totally what I’m trying to do, yes. I couldn’t have said better myself – likely because it’s so new I’m still figuring this out!

I should state first and foremost that after working with a really limited color pallette for several years and relying formally on line to communicate something visually, quilt-based paintings presented an opportunity to introduce a range of color, paint quality, and compositional movement as a result of shape-based rhythms. When I speak about my work, I so often limit myself to talking about ideas, but at heart I think I’m a strong formalist, and projects can come out of a formal craving that I might be feeling – perhaps in relation to whatever it was that I was doing before.

But yes, absolutely, the play between flat and deep space happened immediately for me. I like to think of this dyad as being reflective of the kind of personal viewpoint one can take on, which is similar to what we were talking about earlier. You can see the immediate, up close details of your experience, or you can zoom out and look at your experience in a larger context, as part of a larger story. I feel like these two spaces—the intimate and the immense—these really are my spaces. Describing anything in-between is really challenging for me. Quilting them together into the same piece becomes a kind of stand-in for these kinds of perception. Additionally, quilts have a strong relationship to a grid, as does the history of abstraction, and that parallel really excited me as well. It’s very new territory, but I know you know what I mean when I say that as soon as I happened upon it, it clicked, and felt ripe.

It wasn’t until I photographed my partner’s son holding a finished piece in our yard that I realized how much of a shield these paintings could be and the idea of a painting as a form of spiritual protection came forward.

Quilts—at least a lot of the quilts I’ve been looking at—have been historically made as a means of survival and created out of whatever was at hand. I’ve been reading a lot recently about the incredible Gee’s Bend quilt-makers, many of whom stated directly that although they were certainly engaged in the formal qualities of their work, that quilting was a necessity for them—not a pure expression— to keep yourself and your family warm in the winter. This combination of making and survival resonates strongly with me. I’m reminded of the title of a painting by the artist Magnolia Laurie, The Aesthetic Impulse is Second Strongest, After Survival. Based on experience, I know this sentence is true. Does this resonate with you, Jessica, and with your studio practice? The social realities you’re addressing directly in your work are quite serious. I wonder how you would respond to this concept of making as a means of survival?

Jessica: Well, I’ve never been the kind of artist that has to make work every day in order to “survive” or be content. I tend to work in spurts, being extremely productive for months, then taking a break for a little while I decompress and let new ideas simmer. With a family and a full-time job, I honestly think I survive by being able to not work in the studio every day. The quote you mention speaks only to aesthetic impulse, while for me, I’d actually argue that my studio practice reaches beyond the visual into the social, as I think about how to respond to the world around me. In a new socio-political era, where I generally feel helpless about our changing country, I find that thinking about how I can use my work to initiate a dialogue does in fact sustain me, or act as a form of survival. It keeps me going. And when my job and family keep me running, if I can’t get in the studio for a couple of hours, I will inevitably get crabby and feel in a fog. When I’m there, it brings me back to center. It makes me feel like myself again.

That’s the practical side. You are right, the issues I’m addressing in my recent work are quite serious and do in fact address survival in a more literal way. I worry about my family and the challenges my family and many others may face under this new administration, but do I think my work will help us survive? I doubt it. In many ways, I think the quilts with their softness and flimsiness are akin to sending thoughts and prayers to someone in need. They come from a deeply felt sentiment, meant to do well, but in reality, they may not have any direct impact. It speaks to that sense of hopelessness, that we have a big job ahead of us and we may not effect any change. During times of political unrest, however, artists often find themselves a target of the administration seeking power, and this proves that something we do perpetuates a spirit of survival that is deemed a threat. That admission, that artists may be perceived as a threat, inherently proves the power of what we do. So does art making and expression inevitably help people survive? Yes, I think it does. How the aesthetic impulse factors in, I’m not so sure. I think that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Brian: Agreed, but it’s also a recognition of an iceberg. We understand intuitively that there is more than meets the eye. The appearance of something speaks about the people who have made it, and the realities of their lives—sometimes poetically, as is maybe more the case with my work, and sometimes politically, as is maybe more the case with yours. In the end, the work’s strength lies in something otherwise ineffable, being made visible. And that’s powerful—that’s the admission you talk about. As disparate or as sporadically similar as our work may be, I feel that you and I have a shared mission of making the invisible visible.

Jessica: Absolutely. This too is another overlap that I believe grew out of our seminar in contemporary art in grad school, where we were tasked with making a work that “makes the invisible visible.” You focused on making yourself invisible through silence, I focused on visualizing an image of my family I’d never seen before, and both pieces were pivotal in our trajectories thereafter. I think this just verifies how powerful those shared experiences between colleagues and friends can be in terms of their consequence on the creation of work. Inevitably, if our work grows out of our lived experience, it’s only natural for two independent bodies of work, made by two independent artists, to overlap when the creators of that work share a special bond in time, space, and experience.

Brian Hitselberger is an artist living and working in Athens, Georgia. He teaches painting and printmaking at Piedmont College.

Jessica Wohl is an art professor at the University of the South in Sewanee. Her exhibition “Love Thy Neighbor” is on view at Staple Goods Gallery in New Orleans through April 2.