A museum is a home. Clean, pristine walls bear the marks of makers spanning generations as one walks across with precarity. Across the interior of what museums can house, intimate archives of artists are important and pressing in the digital age, a world that can be easily manipulated through selectively altering and deleting files with the simple click of a mouse. There’s also access limitations to archives within institutions that require requests for in-person viewing, a policy on how many images can be reproduced and received, along with the cost and copyrighting that is placed on artifacts donated to these spaces. Despite all efforts to salvage the memory of the physical with digitization, scanning, memory cards, and hard drives, there’s really nothing like the tactile process of holding and paging through original letters, photographs, and family heirlooms. Sitting across from Arsimmer McCoy, a Miami native, performance artist, educator, and poet—the inherited artifacts overflow across a wooden dining room table in the Carol City home that belonged originally to her maternal grandmother, lovingly known as Miss Mary.

A home is a museum. Walls are imperfect, aged with wear and tear, as one walks in comfort behind closed, ancestral doors. I witness the years of neglect of my late paternal abuelo’s 1950s home in Hialeah when he passed away in August 2023. I now respect the dedication, time, and financial investment that a home begs of one’s hands as I begin the process of drywall skimming, painting, buffing, and balming repairs that were never started or finished. It is a museum that requires care in its most patient form, with the reward amounting to a place to call one’s own. In speaking with Arsimmer about her own labor of turning the home into the Carol City Museum, a privatized sanctity that serves to reflect on her familial lineage in South Florida and in the American South, along with the history of the Carol City neighborhood, I became aware of the sacred need for this preservation in light of financial strains at the hands of the state, rapid county-wide development, and demolition of urban history in Miami-Dade that deems the city’s history as removable and worth sterilizing.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Isabella Marie Garcia: I was intrigued by your work with the Carol City Museum for numerous reasons—from the way Miami fails to appreciate its own history to my own personal adventure in preserving my late abuelo’s home. Can you tell me more about the history of the house in relation to who you are?

Arsimmer McCoy: This was my grandmother’s home, originally built in 1967. My mother bought this house for my grandmother in 1976, when she started working for Delta Airlines. She was one of the first Black hires to work for Delta ticketing reservations, and she started off at Dadeland Mall down south.

Yeah, in the mall you could actually get tickets for flights. What a time, right?

Then they eventually moved to a Coral Gables office, and she did well for herself, so she bought this house for my grandmother. My father worked for the county as a risk manager. Eventually, he would go up to litigation. You know, they were up at the crack ass of dawn, waking up at like 5 AM and working till 5 PM in the evening. Between my grandmother’s home in Carol City and my grandmother’s home in Fort Lauderdale, I would be with my grandmas.

A lot of time was spent at this home as a kid. I would also live here while I was in college at Florida Memorial University. I stayed in the dorms my freshman year. There was nothing in here at the time. God, after my grandmother passed away, we put the home on Section Eight to kind of keep it and keep money, to be able to take care of it, because my mother did not want to sell this house, even with the bills piling on and all that. She was like, Nah, that’s a no. So she put the house on Section Eight and when I decided to move in, you know, they took it off, and I was staying here with just a mattress and a little TV. Eventually, we got proper furniture, hooked it up, and got roommates that also went to Flo Mo, and lived with me. Then I moved out when I had my daughter in 2010 to move in with my parents so I could have help. When I got married, I moved back in, so this house has been a part of every chapter of my life. It has been a shelter for me for every chapter in my life, even my divorce. Don’t put anybody else’s name on your shit.

I was able to even have this home during the pandemic, and be here, thrive here, and now I’m here, living and raising my child here and now, turning a new chapter for what this house could be and what it could look like for the next transition in my adulthood.

IMG: To see a house that has so many features of an era from so long ago, especially in Miami that is becoming more and more “white cube,” and that also is so interwoven in your familial lineage, is comforting. What was the motivation or driving factors that birthed the Carol City Museum?

AM: I want the museum to feel like that, the nostalgia—that familiarity. I also love that the home is so grounding, and it’s so cozy, even the terrazzo floor, it just takes you back to a different time in the city and houses you would go into back then. My grandmother, she was that girl in photos, you see her with friends, partying. She held a number of odd jobs and she also kept foster girls here at this home. Still to this day, I’ve had people pop up here and be like: I remember staying here at Miss Mary’s house. They’re all mad older now, growing with their own families and kids, but it’s cool to know that she was instrumental in a lot of kids’ lives.

I also want people to come in here and just see the work. Maybe they don’t know the artist, but they’re like, man that looks like me, that feels like me, and I’m also in a safe space that feels like home, where I can experience this work in comfort, right? And safety, you know, without the white walls and the queues. I want that for other people, where they can stand there for hours and just try to communicate what they’re feeling between themselves and the work.

The history of Carol City is extensive, like where I’m from, Richmond Heights, down south. Carol City and Richmond Heights were like mirrors to each other. Spaces set in stone for Black folks. Richmond Heights was built for Black veterans, which allows for generations of wealth. The passing of real estate and built-in networks. Carol City, which was majority farmland like the Heights, was another space where Black people could get affordable housing. It was developing. Both areas were affluent Black communities. They bought houses for families, nurses, postal workers, drug dealers, lived and thrived here. Technically, my home is considered Norland. People actually born and raised in the area know the divisions.

IMG: There’s the balance of running a private museum within your home, a deeply private space. How has the process of collecting, archiving, and quantifying the history of Carol City been for you? What surprises / challenges have you faced and are willing to share?

AM: I’m in the preliminary stages. I’ve been doing both voice recordings, that’s been my primary archiving for right now, and I’ve been going to different neighbors in the community, getting their stories about growing up here, as well as asking them for artifacts, anything they would like to donate to me, and coming up with a plan for preservation. For a lot of them, they’re just like, Here, take it, you know. For me, it’s like, what can I give back to you? How can I still, maybe this is not a monetary exchange, but what exchange can I give to you?

I’m creating a membership program where community members can sign up and receive artwork for free. Special exhibition projects for some of the neighbors I’ve met, who are artists in their own right. Like My neighbor down south, Mr. Parks is a painter and horn player. He would like to show some of his work now that he is retiring from the postal service.

Some folks love to archive a certain thing. Mr. Brown, He’s got Freaknik videos from Atlanta, right? Mr. Brown has videos and all types of stuff from that time. There is the crass of it, but it’s just absolute unfiltered Black joy. My sister went to Daytona, the PacJam. He’s got videos of him and his homeboys showing off their outfits, their chains, their camaraderie, and getting ready to have a time together. I’m like, well, maybe the exchange for Mr. Brown and I, is assistance in archiving his collection and a public exhibition through the museum.

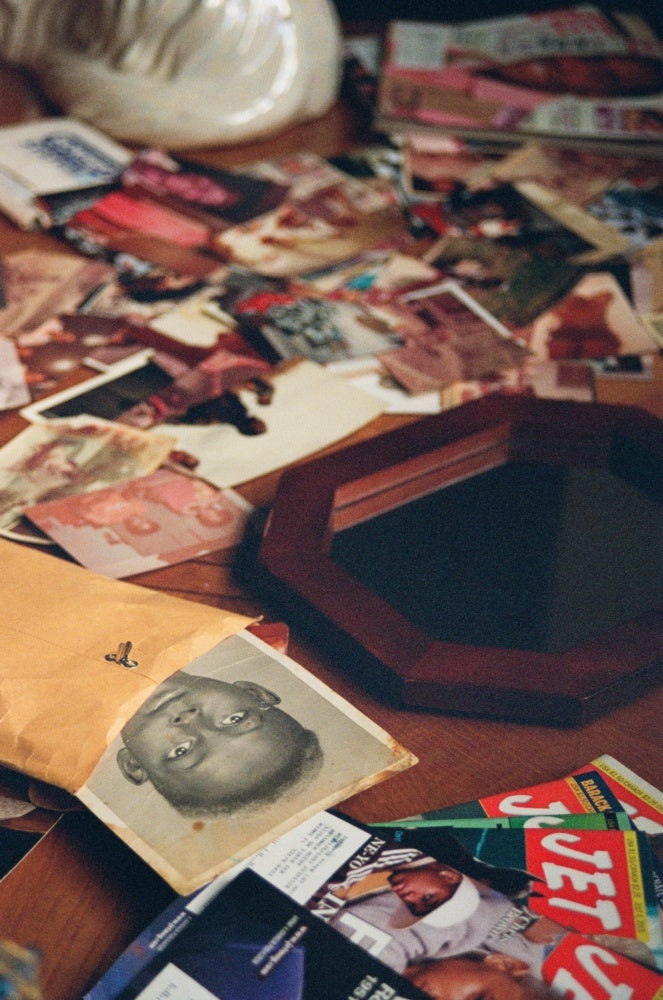

I love the voice. I love the actual storytelling and recording those stories and getting to see all their photos and pictures. I really feel photography for the Black community was such a godsend, because we had nothing to go on before then. Just the continuous passing of story and hoping the message stayed intact. Memory wasn’t always polished; it wasn’t always together for some. Some of us were lucky enough to have photos here and there, but the majority didn’t even know the lineage where they came from. I’m making sure I have every photo of everything, of all my family. I mean, you would be surprised at the amount of photos that people have in their homes and videos.

I really feel photography for the Black community was such a godsend, because we had nothing to go on before then. Memory wasn’t always polished, it wasn’t always together.

I’ve also noticed there is a fear too, from a lot of my neighbors in handing over things and talking about certain things, they’re leery of me. They’re not really sure what my MO is. Even if I tell them that I’m just making this museum, I’m not rich, I’m not from an institution. They’re still wary and I respect that, and I know what that stems from. That stems from being told one thing and another thing happening. It’s being told by people you know, coming to them and offering them good things and saying that they care about their stories, and then finding out that’s not the case, or having their stories used against them.

I started off with making this little paper that I would put in some people’s mailboxes that just said my name, a little bit about the museum, if they’d like to contribute, and to call or email me. I didn’t get a lot of phone calls or emails, but some folks did and I started off going to them, and then they told other people. It became a game of telephone and word of mouth. I was in one woman’s home, and her homegirl came over, and she was like, Oh, well, you need to come by my house, because I got this, this, this, this. How they light up, just remembering. There’s so much power in memory, so close to you. It’s been really cool to see it organically happen, because I believe that’s how the museum should operate: organically and beautifully and wonderfully and honestly.

IMG: I love how personable you’re about going to your neighbors directly, their mailboxes, and offering them these opportunities to contribute at what feels comfortable for them. There’s no pressure to give anything, but it’s a way of really going to someone personally and acknowledging that their lives deserve to be saved and archived and known, and that it’s very special to be a part of this community for however long the people you’re meeting have been, whether it’s this generation or multi-generations. What is your favorite archival piece / history fact in the museum, and why?

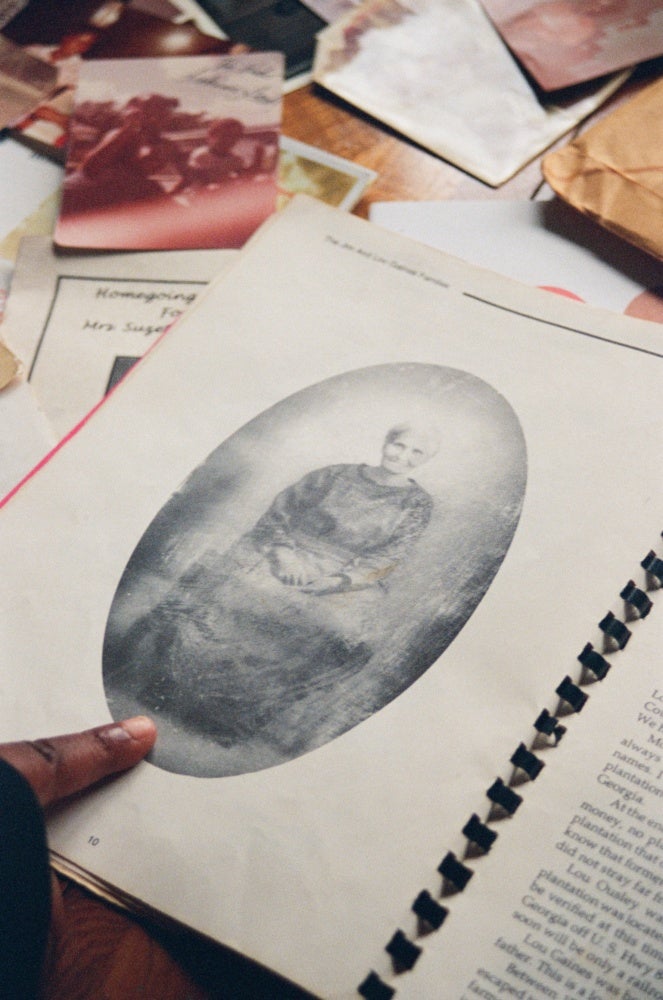

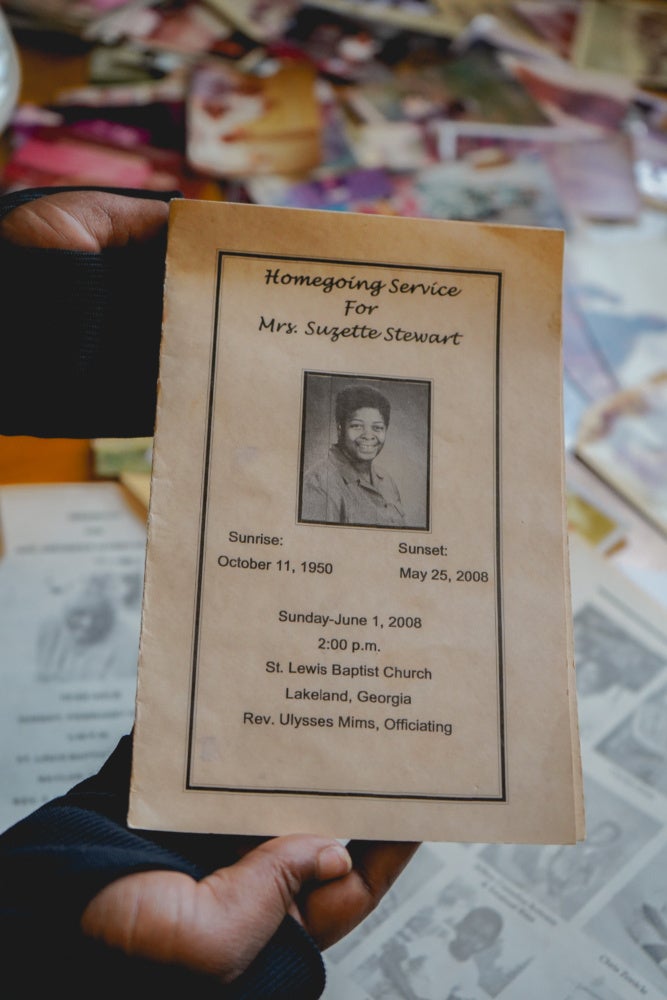

AM: I immediately thought of my family reunion history book. It’s just a breakdown of our tree from beginning to end. My mother lived between Miami, Florida, and Lakeland, Georgia, with her side of the family hailing from Georgia and then merging into that Georgia-Florida pipeline. Everyone that passes away on this side of the family is buried on the same cemetery plot of land in Lakeland. I really appreciate this because honestly, I didn’t know that having a family reunion was special. In my head, every Black person in the world has a family reunion or documenting it, and you find out that nah, this is rare. This is actually not the norm for a large percentage for people of color in our community. My mother was on the activity committee and really helped spearhead this preservation of family history. Mary Lou Gaines was top of the matriarchy, and I have her picture here in the house.

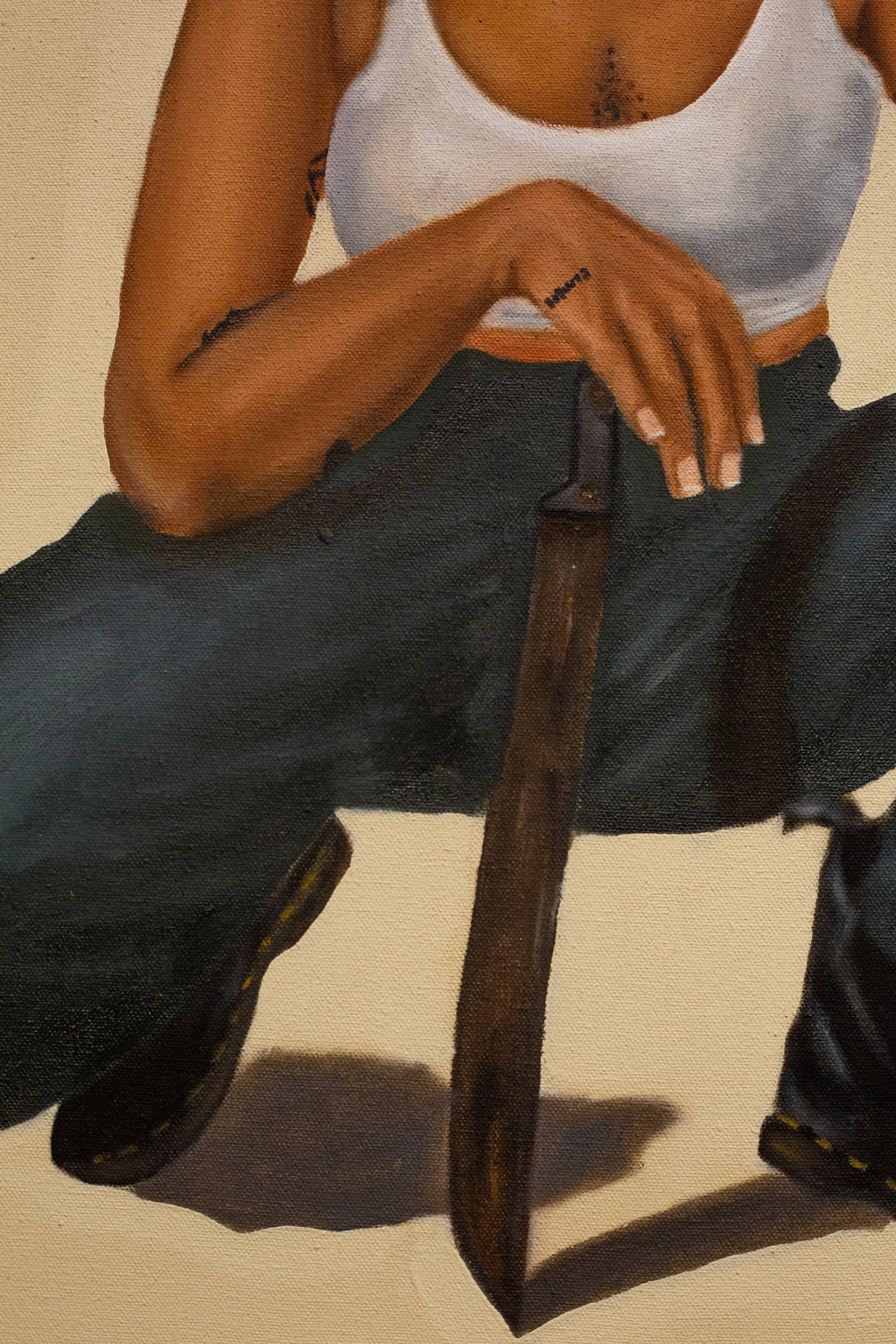

There’s also Dr. Wylamerle and James Marshall’s chairs from their home. He was the first president of the homeowner’s association in Richmond Heights. Well, he passed away first, and then his wife passed away after, and the family sold everything, sold the house, and I was grateful that my mom was like, I want to go and get some things. She just went over there and she was like, my daughter has a museum she wants to do, and she wants some things from the Marshalls. They gave her the rocking chairs and now they are here as part of the museum’s growing collection of historical artifacts, which I have also loaned to local artists to activate thier work if it applies. Cornelius Tulloch’s Poetics of Place and Sydney Maubert used archival photos to inspire her new paintings for her solo exhibition titled Smile For Me: The Flea. If folks want to use them, I let them take certain pieces if they feel it works for their performance, exhibition, or staged photograph. That’s how the museum becomes mobile.

The museum is language and poetry-driven. Because I’m poem, it started as a poem. A conversation on what was, what is, and what can be. What’s coming up next is that we open it for visitors to experience. A museum that is also a hub, free library, and event space. I want students coming home from school to have a space to go to that’s safe and feeds them mentally & spiritually. I want elders to play dominoes here next to a sculpture by a local artist in the backyard. I want intimate concerts by local artists and fish fries. I want my people to have access. I even got this crazy idea to do a farm-to-table candy lady situation. Cause deadass, we need the Candy Lady back. The original OG entrepreneur.