Everyone plays “Little Birdie” different, though the melody is always familiar. Each rendition of this traditional folk song lives in its own world—compare Ralph Stanley and Roscoe Holcomb’s versions of the song with Morgan Sexton’s version, the subject of this article.

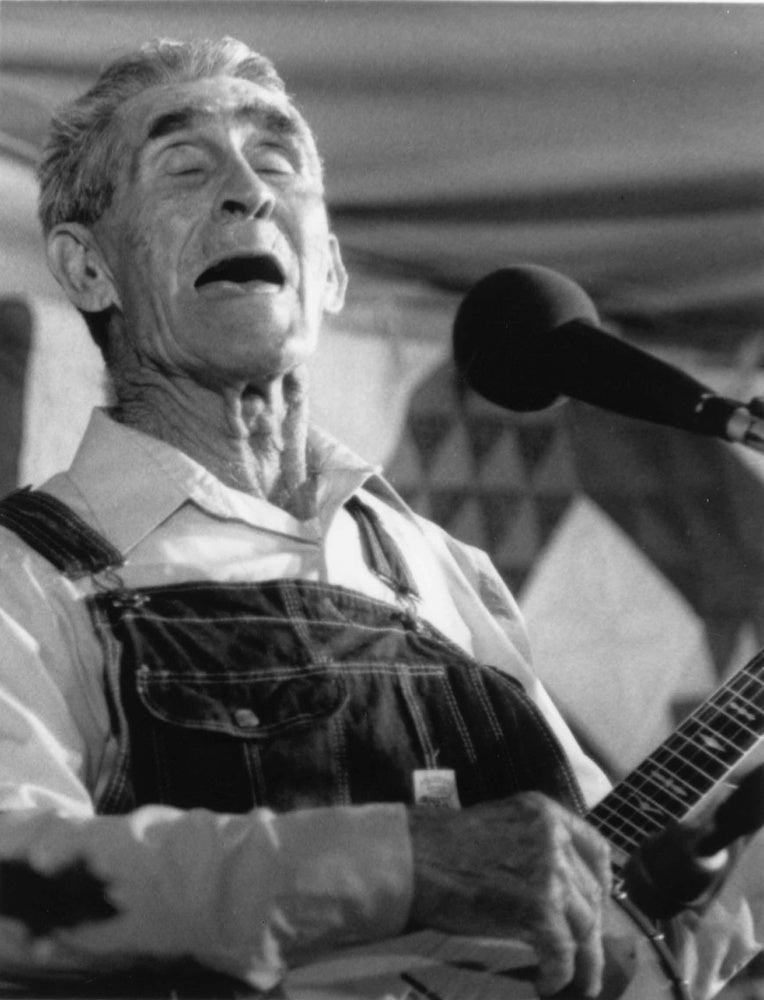

Sexton’s “Little Birdie” is a sad song, full of love. I remember talking about Sexton with a veteran bluegrass musician from the West Coast, and she teared up recalling when she heard him play the song on stage decades earlier. There is something particular about Sexton’s sound that resonates across space and time.

Not having had the fortune of meeting the legendary East Kentucky banjo player in this life, I learn his music through the surviving recordings of him, most of which are held in the Appalshop Archive. The video above is a shortened clip from this video. It was recorded in June 1989 onto a U-matic video tape at the annual Seedtime on the Cumberland festival, in the gravel parking lot of the Appalshop building in downtown Whitesburg, Kentucky. Sexton sits in a small circle with two other musicians in what seems to be an informal banjo lesson or jam session. Sexton also performed on the Seedtime stage that year, but this setting feels different—maybe because there is less pressure. The handwritten label on the spine of the tape says: “Seedtime ‘89, #9, Morgan under trees.” (Sexton had released his first record in January of that year. Titled Rock Dust, a reference to the coal dust that causes black lung, the album appeared on Appalshop’s June Appal label.)

There are formal musical aspects of Sexton’s playing that set him in his own category. To play his music, you must internalize his crookedness. The majority of his musical life was spent playing alone at home, and the shapes of his melodies reflect that—phrases extend a beat or two longer than you’d expect, or turn off in a new direction. The sound is entirely personal. If you play an instrument, try breaking down Sexton’s “Little Birdie.” You will find a flow of oblong phrases, each one distinct. When I learned this tune, there was a moment in the process when, once my ears and fingers had become comfortable with the mechanics of each phrase on its own, there was a transformation: the sounds changed from a confusing jumble into an easy stream.

Zooming out, you could break the banjo part down into two different zones: one fingerpicked, higher pitched, and melodic; the other up-picked (notice the change in his hand movement), creating a drone with repeated hits on the low fourth string of the banjo. Sexton moves back and forth between zone one—the song’s primary melody—and zone two—low, droning rhythm. This movement continues through both the instrumental and the sung verses, though the structure of the melody is different in the instrumental.

“Little Birdie,” . . . will astound you all the more when you listen carefully and realize that while Morgan picked the strings with his thumb and forefinger between verses, he was gently drumming on the banjo head with his middle finger.

Paul Brown

Sexton made use of a deep well of sounds, and part of his unique skill was combining different techniques, which Paul Brown describes in the liner notes to Sexton’s album Shady Grove, which was released in 1992, the year Sexton died of cancer at age eighty-one. Brown writes:

A banjo is not a group of bells; it’s a drum with strings. Many banjo pickers fail to grasp this in a lifetime of playing, but Morgan understood it intimately, and, we may surmise, for most of his days. Just as he let notes ring, he chose unusual and striking moments to stop strings, to play percussive-sounding high or low notes, and literally to beat on the banjo head. “Little Birdie,” one of Morgan’s most evocative and affecting songs, will astound you all the more when you listen carefully and realize that while Morgan picked the strings with his thumb and forefinger between verses, he was gently drumming on the banjo head with his middle finger. During an advanced banjo workshop at the Augusta Heritage Center in Elkins, West Virginia, we asked Morgan where he had learned to do this. He answered that he had come up with it himself, it didn’t seem that hard, and for him, it just went with the song. It was needed.

In this video, recorded at Sexton’s home in Linefork, Kentucky, in 1990, he is asked if he’s still trying to improve his playing at age eighty-seven. He replies:

Turning in my voice, that’s what I’m trying to get to now. Singing, as you sing a word, try to turn it off in a good, mellow tune, so it’ll sound up better. That’s about all it is. And my banjo playing too. Change the notes, most time it’s a flat note. I’m trying to change that note, and pass that note up, and it will have a good mellow sound, and ring right on, and correspond right on in with the rest of my music. . . . Now Ralph Stanley, music and everything, all his music, the turning in his songs, and his banjo, seem like it’s got a good tone to it, turning off from one note onto another note. That’s what I’m trying to get at, have a good turn to it. Not change my playing at all. Just trying to have a good tone, changing in the notes in the song, and words.”

Sexton is telling us how to move from one thing to another, across a boundary. His words illuminate the mysterious, universally resonant quality in his own playing, though I believe it is not fully describable in written or spoken language. I think of it as modular, the way he moves with ease from one entirely unique section to another. This pattern continues through the Appalshop Archive as a whole. Explore this page or this one and you will find a collection of doorways, each leading to another world. All these worlds live together in the archive. It is because of their differences that they hold together so well.

When he got his Black Lung check, he decided he wanted him a Subaru.

Tounsel Haynes

On Wednesday evenings I teach fiddle up at the Carcassonne Community Center, in the same part of Letcher County where Morgan lived. One of the people I teach is a man named Tounsel Haynes, who knew Morgan, and told me about his wide-ranging skill and strength. Morgan could plane boards by hand, Tounsel told me. He would “take a axe, man, and you’d think it’d been run through a planer.”

As a teenager Tounsel worked for Morgan cutting grass along gas pipelines, and recalled that Morgan could use a mowing blade—a two-foot-long scythe—“as fast as he could walk.” Morgan also told him how to make liquor, how to stir the mash by hand, how to tell by the consistency when it was ready to be put in the still. “My dad said Morgan made the best liquor he ever drank,” Tounsel said.

In most of the archival recordings of Morgan, he appears as a sweet, sensitive older gentleman. As I’ve realized from talking with Tounsel, that’s not all there was:

He hated animals . . . he’d kill every deer, weasel, minks, because they eat his chickens and his corn and stuff—he didn’t share. And he didn’t get along with a lot of people. The people lived down the holler from him was riff raff, really. They’d steal and lie and cheat. They didn’t mess with him, and he didn’t mess with them. Yeah, people was scared of him. He packed a gun, and he would shoot your ass.

Tounsel drove Morgan around as his health declined in old age, which bothered Morgan, having to rely on someone. He liked to take care of his own business, “independent as a hog on ice” was how Tounsel’s father once put it.

He drove an old Jeep most of his life. And he got Black Lung. When he got his Black Lung check, he decided he wanted him a Subaru. So I drove him to M&M’s Subaru over in Pikeville, and he’s just out here looking at them, you know, with an old pair of overalls on, and you know how Morgan looked. And this guy, this salesman, he kept trying to get him over into the old used cars. You know, “Right here, now this is a good one,” you know. Morgan kept looking at this new, nice Subaru, man, a wagon, it was really a nice vehicle. He finally told that guy, “I wanna try that one right there.” So he wanted me to drive it. We started down the road and he pulled a tape out—of his, that he had made—and stuck it in the cassette deck. We’s listening to Morgan picking, you know, guy sitting in the back, no doubt that guy’s thinking, Well this old dude here couldn’t buy damn two packs of chewing backer at the same time. So when we got back, Morgan said, “I’ll take that one right there.” That old feller said, “Well Mr. Sexton, how are you gonna finance it?” And he had overalls on, he reached down in there, he said, “With money.” He turned out the money and bought that thing. If I’m not mistaken he give them like thirteen thousand dollars that he had in his pocket.

One last doorway into Morgan Sexton’s music. Anne Lewis directed an Appalshop documentary called Morgan Sexton: Banjo Player From Bull Creek, which was released in 1991, shortly before Morgan’s death in January 1992. The raw camera tapes from this film were in the Appalshop Archive vault when it flooded in July 2022, and though they were soaked through with toxic flood water, the tapes have now been cleaned and digitized by Specs Bros, a media preservation lab in New Jersey. The sound and picture on these tapes is still intact—an enormous relief because only a portion of them were digitized before the flood.

On one of these tapes there is a moment when Anne, sitting in Morgan’s living room, asks him, “What makes a banjo ring?” Morgan’s reply is perfect: he plucks a tune on the strings near the bridge then plucks farther down toward the neck of the banjo, where the strings are looser, where, Morgan says, “it rings entirely different.”

Editor’s Note: This essay is part of a four-part series spotlighting flood-salvaged artifacts from the Appalshop Archive, which houses the largest media collection of Appalachian history and culture in the world.