In his seminal 1997 text, Martinican writer, poet, and philosopher Édouard Glissant called the waters that carry ships the “blue savannas of memory and imagination.”[1] The space between shores is an abyss marked by uprooting and re-rooting, but if we stay in between these states, a poetics of relation starts to emerge. The passage of migration can be defined by the pining for a place of origin that slowly dissolves into memory, or a future harbor that soon becomes familiar, crystallizing new patterns of the everyday. But the poetics of relation found in the place in between allows for a measurement of one’s self through difference.[2]

Glissant was born and raised in Martinique, a Caribbean island under French colonial control in the Lesser Antilles.[3] Another Caribbean island that is subject to colonial rule is Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory of the United States. Martinique and Puerto Rico might seem to point toward the evils of colonialism, most notably through the withholding of autonomy and self-determination, prompting progressive scholars like Glissant to argue for emancipation. But Glissant was hesitant to rush toward nationalism and instead looked to the geography of the Antilles as a metaphor for a new kind of political structure, imagining that each island represented a form of identification and their agglomeration was a kind of politics that embraced multiplicity. He was interested in the particular creolization that the Caribbean produced, a mixing of traits that didn’t identify with the colonizer but at the same time resisted the rush toward a return to one’s ethnic roots that was appealing to others in the African Diaspora.[4] Glissant helps us to think about how water characterizes a particular materiality for borderlands—they are spaces of indeterminacy that can also become a metaphor for new kinds of political determination. In this sense, the Caribbean Islands are not subjects to be seen as victims but, on the contrary, their creolization provides an opportunity to invent a new form of political subjectivity. I believe that this kind of political space, even as it is found in the metaphor of water, permeates the work of artist Alia Farid.

Farid grew up between Kuwait and Puerto Rico and continues to work between the two locations to this day. Like Puerto Rico, Kuwait’s history and geography are shaped by water, albeit in very different ways. Puerto Rico is an island prone to the heavy rains of increasingly severe hurricanes. Kuwait, on the other hand, is largely desert, being at the northern tip of the Persian Gulf, though Kuwait City began as a fishing village in the sixteenth century.[5] Just above the country’s northern border with Iraq, near Basra, there is marshland, which was a traditional source of fresh water for the region. Farid’s recent video Chibayish (2022) is titled after the marshland and follows a group of boys herding water buffalo through the region’s miry terrain. They romp through the reeds, splash in the marsh’s shallows, and call their flock with sounds that combine Arabic language, animal mimicry, and song. The borderland was a site of contention during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s and the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Following this failed invasion, Saddam Hussein ordered the draining of the marshland, producing an ecological and social disaster that included the displacement of the local Shi’a population and the near eradication of an ancient and rare wetland.

Glissant helps us to think about how water characterizes a particular materiality for borderlands—they are spaces of indeterminacy that can also become a metaphor for new kinds of political determination.

Two other bodies of work by Farid that similarly address the waters at the border between southern Iraq and Kuwait are In Lieu of What Was (2019), first presented at Portikus in Frankfurt, and In Lieu of What Is (2022), recently presented at Kunsthalle Basel. Both are large, off-white, resin sculptures that are augmented representations of vessels commonly used to transport water from these marshlands. The sculptures reference a traditional practice followed to this day in which water was brought from Iraq in vessels along the Shatt al-Arab river, in boats used by pearl divers. Today, most water in Kuwait is treated in desalination plants, a process that requires an enormous amount of electricity. Thus, Farid’s sculptures raise questions about the ecological sustainability of water consumption in the region.[6]

The working title of Farid’s most recent body of work is Migration of Form. The artist founded the project on research about migratory patterns that mirror her own. Following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Farid’s family temporarily relocated to her maternal family’s home in Puerto Rico. Her family’s story is one droplet within a wave of migrations from the Middle East to Latin America during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In upcoming exhibitions at the Power Plant in Toronto, Chisenhale Gallery in London, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, she will show works that grow out of a larger archival project that looks at Arab immigrants in Puerto Rico, with a particular focus on the island’s Palestinian population.

One thing to note about this project is that Puerto Rico, while technically being a territory of the United States and with limited sovereignty, has a long-standing connection to both the Caribbean and Latin America. Prior to American colonial control, it was a part of the Spanish Empire and, in some ways, has more in common with its neighbors to the south than to the north.

There are over 700,000 Latin Americans of Palestinian origin in sizable enclaves within Chile, Honduras, and El Salvador. One migration wave was caused by the fall of the Ottoman Empire in the early twentieth century, but other significant drivers include the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip, which followed the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948,[7] and the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967, a devastating slew of events that produced an estimated 7.2 million Palestinian refugees worldwide.[8]

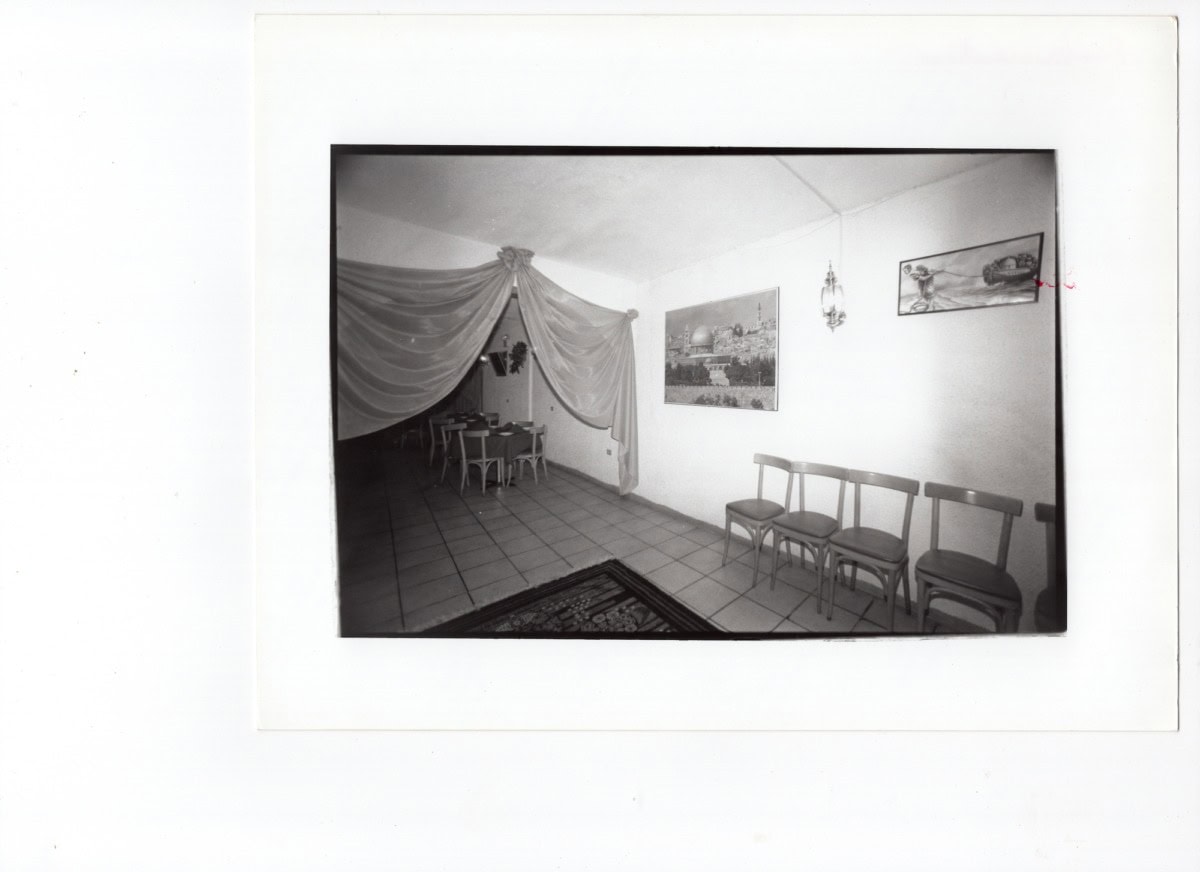

According to Farid, many of the Palestinians in Puerto Rico came through immigration pathways that follow these histories. Thus, the Palestinian community on the island can be traced from the Ottoman-era Levant, through Latin American communities in Chile, Brazil, and Colombia.[9] For Migration of Form, the artist posted fliers asking for any Puerto Ricans with Palestinian roots to contact her and then gathered photographs and documents from respondents. She was looking for public spaces where these immigrants connected with each other and found Islamic centers, pharmacies, gas stations, restaurants, and clothing stores—all Palestinian-owned or operated. The visual and material culture of these spaces are important. One research image depicts a mosque in Ponce, Puerto Rico’s second largest city. The mosque’s orange-striped minaret rises above the more common vernacular architecture of the island. In another image of a shop interior, a large photograph of the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem hangs next to a drawing of an Arab man. In this drawing, the figure pulls a rope attached to a ship that seems to have a miniaturized version of the Al-Aqsa Mosque on top of it. The trope of an image of Al Aqsa is common for the Palestinian diaspora, but the image of the third holiest site in Islam being mobile is curious. Perhaps, it signifies the way in which Palestinian immigrants carry the memory of Jerusalem with them.

Farid pays closer attention to vernacular material and visual culture when looking at Palestinians in Puerto Rico. In her growing archive, we can see idiosyncrasies, whether they be mosque architecture or signs for comida Arabe (Arab food) advertised in a Palestinian restaurant. Farid is producing woven textiles in Alexandria, Egypt, as part of this archive, preserving a tactile everyday materiality. She embraces and highlights the nuances of the community’s visual culture that she has found and eschews minimal forms.

While much of Farid’s work seems to grow out of her biography, the artist resists the tendency to act as a native informant. Indeed, Farid’s work evokes obscured histories that push against standard American or European narratives, but she does so by inhabiting Glissant’s poetics of relation: by finding through lines that connect seemingly disparate regions where creolization is already underway, cultural spaces distinguished by complex histories of emigration and immigration.

For this reason, I love her film At the Time of the Ebb (2019), which was filmed in Qeshm, an Iranian island in the Strait of Hormuz. The film depicts the celebration of Nowruz Sayadeen, Fisherman’s New Year, with a group of people dancing, singing, and playing music in a small pink room. Some wear white cloths stretched over their bodies as they bounce like ghostly apparitions to the rhythm. A different scene takes place on the beach, where figures with their faces painted white don tall, conical hats and woven beards. They hold palm leaves and chase after one another, followed by groups dressed as animals including water buffalo and camels. The pageantry seems syncretic, surreal, and resists the authoritative gaze of ethnographic film. Instead, viewers are invited to sit in the space outside of what can be categorized or understood. As we watch this film, we feel the affective pull of images and sounds and are encouraged to be present with them—like standing on a beach and feeling each wave of water lapping at our feet. The fishermen celebrating Nowruz Sayadeen feel grateful for the water that sustains the fish, which, in turn, sustain them. But to be present with the waves produces a feeling that is equally available on the islands of Qeshm and Puerto Rico. It is a feeling that Glissant understood from his history on the island of Martinique. It is a feeling that is physical, yet filled with metaphor when we are reminded that water is what binds us together, despite the appearance of distance or difference.

[1] Edouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 7.

[2] It should be noted that Glissant was describing the Middle Passage, the horrific transportation of enslaved Africans against their will. While I am not conflating this experience with other forms of migration, I am suggesting that the diasporic condition can account for multiple histories. Glissant begins with the African diaspora to describe a multiplicity of identities.

[3] Since 1946, the French National Assembly has categorized Martinique as an Overseas Department of France, though in the years following WWII, campaigns for full independence and tensions between the West Indian populace and French colonial power have grown. As with many islands located within the island group, colonial forces have treated Martinique as an offshore account or foreign-based asset.

[4] Édouard Glissant, Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays (University of Virginia Press, 1989), 235.

[5] Michael Casey, The History of Kuwait (Greenwood, 2007), xi.

[6] Alia Farid in conversation with Elena Filipovic at Kunsthalle Basel, https://youtu.be/5CIEILhTamM.

[7] Referred to by Palestinians as the nakba, or the disaster.

[8] Ronaldo Munck and Pablo Pozzi, “Israel, Palestine, and Latin America: Conflictual Relationships,” Latin American Perspectives 46, no. 3 (April 2019): 4–12.

[9] Alia Farid, interview with the author, April 30, 2022.

Alia Farid has forthcoming solo exhibitions at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery, Toronto; Rivers Institute, New Orleans; and Chisenhale Gallery, London, all in 2023. Farid was among the artists selected for Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept.

This essay is part of our yearlong series Invasive Species.

Find out more about the three themes guiding the magazine’s publishing activities for the remainder of 2022 here.

Become a member or make a tax-deductible donation below.