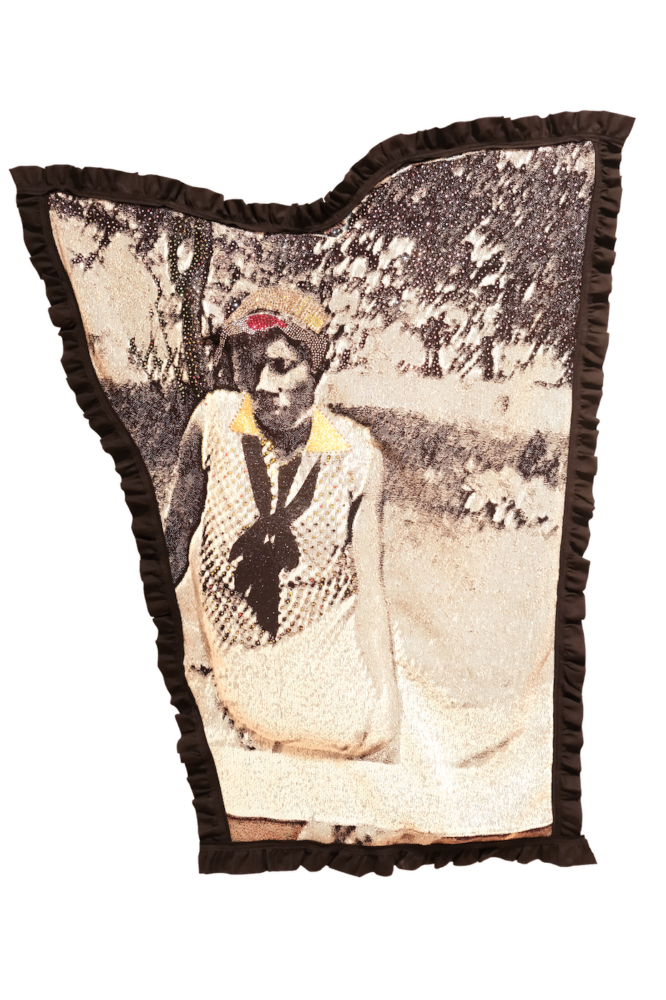

The tapestries featured in Akea Brionne’s series, “An Ode To (You)’all” have a romantic quality to them. Depicting scenes of Black Mississippians in pastoral landscapes, each work highlights a photograph from the artist’s personal family archive. During her gallery tour at the Mississippi Museum of Art, she described the tapestries created in honor of her three great-aunts (the Phelps sisters) and her great-grandmother. These four women who never left the South made it possible for the men in the family to migrate north.

Embedded within the fabric are coded images, with intentional artistic decisions dictating what viewers see and what is cropped out of the frame. Reflections in the Grass includes many romantic elements: themes of solitude, aesthetic beauty, emotional awareness, the transcendental. In Reflections, a slender woman wears a printed blouse with a dark pussy bow tied loose beneath the collar. Seated outside, she leans onto her right arm with her crossed ankles swung to the left side. Her face is pensive and angled towards the ground. The tapestry’s unique V-shape suggests that certain aspects of the scene are not included in the final reproduction — a girlfriend or lover alongside the woman is not in view, but the gaping spans on the left side of the tapestry is prominent, leaving many questions unanswered.

From the archive, Akea Brionne weaves fragments with jeweled thread, summoning viewers to look slowly as they waltz back and forth with her ancestors in the gallery space. These quiet moments require a willingness to imagine with and through the woven portraits, a desire to see their sanctity. Viewing with the same reverence that one might feel with a grandparent’s old yearbook or photo album long-forgotten, visitors to A Movement in Every Direction witness the works with an understanding that each tapestry carries an air of mystery, exposes a memory that we ourselves do not hold. In this way, we bear witness to the Southern Black archive — its porches, its portraits, its people. The ones you would only know if you knew them.

In conjunction with the Mississippi Museum of Art’s recent exhibition, A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, co-curated by Ryan N. Dennis and Jessica Bell Brown, Akea and I met over video call to discuss storytelling, ancestral media, and the relationship between identity and geography. The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Bryn Evans: You are one of four artists participating in this exhibition who was born in the South. And this idea of the South is contested in the exhibition. The notion of the South as a singular region, or an isolated location without through-lines, or undertones, or renditions that resonate throughout the country — even the world — is proven false in the show. Viewers are invited to understand the South as interconnected. And it’s also an affected geography, one shaped with terror and bloodshed and genocide and environmental calamity and other forms of violence, across time-space. Yet, this South continues to be one that moves artists to create and salvage and perform, so that we might be able to conjure something that even remotely resembles the way this place can make us feel. The joy that is birthed here and the love that is birthed here. I remember hearing you discuss your desire to center beauty and tenderness and care. How did that take shape during the art-making process and while you were conceptualizing this body of work?

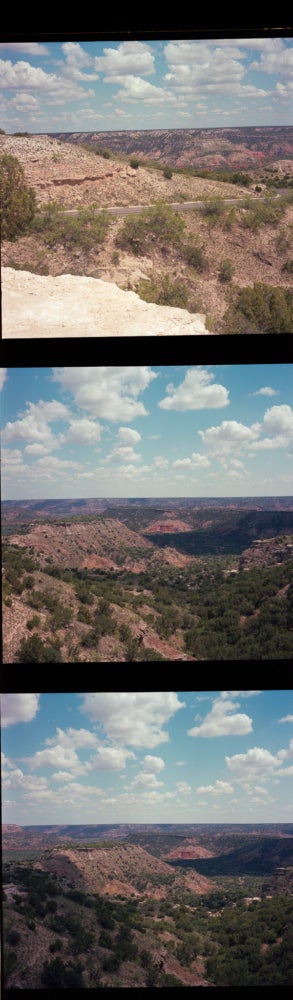

Akea Brionne: The entire process was just my love and care for my family’s story. And also for myself. It was a long time working on this. The process initially began with me, following the same path that my grandfather did — he migrated from Mississippi, then moved to Louisiana, where he met my grandmother. They migrated to New Mexico and had my mom and that’s where she was born and raised. I took that same path, and I was on the road for three months, just by myself. When I got back, I spent the next year creating this work. It took many different forms before it manifested into these tapestries.

I had to figure out how to say what I wanted to say, while honoring both the familial stories I was trying to tell and my story as well, which is now a continuation of those stories. When I did finally settle on the tapestries, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. A lot of the work was literally happening in the fabrication of these tapestries, to the sewing and stitching and re-sewing and the tooling. I put on each of the jewels myself, which was really time- and labor-intensive. But, that to me was the beauty of it. Something that isn’t talked about a lot, within the context of Black life in the South, is the consistency of Black women showing up for themselves and showing up for each other. I wanted to spend that time showing up for myself and showing up for these works in the way that they needed. So I was very intentional with the images that I selected. I decided to work with moments that I found to be quieter, ones that, maybe if I had just printed them out and put them on the wall, would not have come to life or wouldn’t have had the resonance that they have. These moments of communion, gentleness, and love for the space and for one another.

BE: Your work explores the relationship between identity and geography within contemporary post-colonial America, and you engage with themes of cultural storytelling, memory, assimilation, and the performance of identity. When I think of the Great Migration, I am reminded of biography and its relationship to geography, how the body relates to the land, and the ways in which they both remember. How do you choose to record or document these memories in your work?

AB: Most of these memories are recorded by the consistent usage of archival imagery from my family. I haven’t taken new images of my family in almost two years now. Everything I’m working with, both in this show and for some upcoming work, are all images from the past. Some of the memories are from times when I wasn’t even born yet. And though I make so much work surrounding my family, I didn’t get to grow up with them. And especially after Katrina, we have been scattered throughout the South and Southwest, so I have desperately clung on to these images as a way for me to feel surrounded by family, even though for much of my life, I haven’t been. That’s the beauty of working with memories, in the form of images, you can always go back to a moment. That’s also the sadness of working so heavily with memories, no matter how much you look back, you can never go back and you can literally see how much has changed, including the landscape. With my recent work, I’m pulling the geography out of the images themselves by transforming them into these objects that start to animate themselves and speak for themselves and, and take on forms that starts to exist outside of the imaginary. Transferring and transforming them to fabric, and then adorning them, you’re able to really move with the works and they create a geography by just being objects. You can take them in as the light hits the jewels. It begins to become a landscape itself, where the image actually disappears the closer you get to it, until you’re only met with colored threads and jewels. Then, the further back you step, you’re actually seeing the image itself, it comes back into view. It’s a really metaphorical, yet literal relationship that I am building between biography and geography, where the life of these moments really starts to live and speak for itself.

BE: The shimmer brings a cosmic dimension to the work. It helps bend the time and the space a little bit more, with the way that it allows the pieces to move.

As I hear you describe this back-and-forth movement, I am reminded of another type of writing: choreography. The viewing experience requires an active engagement with the work in the space. Because you’re dealing with fibers, there’s a physical aspect to the objects as well.

AB: Before I came to image-making in my teens, my foundation was sewing and making clothes when I was a kid. For a few years, I would take sewing lessons on the weekends with senior citizens in the area. Through those early experiences, I began to love to make things with my hands. Sewing opened a different dimension of creating for me, and it is a nod to the domestic art that a lot of women have been able to find autonomy in. With this work, I was able to return to my own foundations and engage with imagery in a new way.

BE: Earlier you mentioned your personal migration, and the ways in which it resembled your grandfather’s journey. What was that experience like for you?

AB: I’ve always been sort of obsessed with this idea of the open road. But the open road and the “American Road Trip” has always been very steeped in privilege and accessibility. A lot of themes surrounding the road trip has been centered around whiteness, and the physical capacity to feel safe in that journey or to have the financial capacity to sustain it.

My travel took place between March 2021 and June 2021. When the opportunity presented itself, I felt like I had to do it. It also allowed me to slow down in ways that I wouldn’t have been able to otherwise. The road trip was such a great reminder of fluidity — to be in so many different communities and witness as the food begins to shift, as does the music, the landscape, and the colors of the sky. I felt as though this trip helped validate my own individual identity. Moving from where my grandfather came from in Mississippi, and then going home to New Orleans where I am originally from, I could understand the culture shock he experienced. The states are not far apart, just one state over from each other. Yet culturally, they’re very different. Having time with myself in these places just inspired me. And also some of them did not feel good to be in. It helped ground me and gave me a better understanding of who I am and where I respond to.

BE: The work featured in A Movement in Every Direction is not your first time contending with ancestral media or familial archives. Your 2019 series An Archive of Your Own included collodion prints that explored Black maternal relationships.

There is one dizzying family portrait of yourself and two women that really captivates me. The edges of the photograph become blurry ring-like waves — at the center, the three figures stare directly at the camera lens as they hold one another. Can you tell me more about that image?

AB: That particular series was my first declaration to myself of the work I was doing: consciously engaging with the images. I have been working with images of my family for years now , and beyond photographing myself, my family is really my subject. I collaborated with one of my former undergraduate professors on the project, Jay Gould. I was introduced to the process of making collodions through Jay, so it was important for me to work with him because I trust him, and I wanted to be in the images.

I wanted to focus on the matrilineal succession that was visibly occurring, and make sure that it was captured before my grandmother passes, or my mother, or even myself. The series was also rooted in one of my critiques of the archive. It’s no secret that there are very specific people given the roles of archivists, anthropologists, and researchers. I didn’t want the job to be someone else’s—I wanted to have control over how our narrative was going to be solidified. With the tintype, the collodion process, it was often historically commissioned by enslavers who would photograph their property. And so I was thinking about that history. It’s always been so important for me to acknowledge who was taking those photographs, who was photographed, and why, for whom, and where those images have ended up throughout history.

Another aspect of it is the history of the chemistry itself. Until about twenty years ago, there really wasn’t a chemistry that was suitable for accurately exposing darker skin. Of course we are moving away from the mass usage of color photography and color film. But, it wasn’t until chocolate and furniture companies began complaining about their products not being correctly photographed that any sort of effort was made to develop a chemistry that could accurately expose darker skin, or rather, darker tones.

This historical context led me to want to reclaim the medium, and to also create some commentary about the lack of accessibility within the collodion process, which is being reclaimed by a wealth of photographers in recent years. In this way, the series sheds light on how images aren’t trustworthy. My skin tone is not accurately represented in the photograph, neither is my grandmother’s or my mother’s complexion. But it’s a document that people could find a hundred years from now, and they will take that image as fact. Which has always been the problematic element of photography. Until the digital age, not many people outside of image makers and newspapers have understood that images have never been trustworthy documents.

BE: Outside of this exhibition, you are also pursuing an MFA. How’s that been?

AB: There’s been two sides to it. One being the reality of how challenging and exhausting pursuing my MFA has been while being a full-time artist. A lot of people pursue their MFA to figure out how to build and sustain a practice. I’m definitely not at the end of my journey, but I have been working for myself as an artist since I graduated from undergrad. So becoming a student again, while maintaining shows, installs, lectures, and commissions, has definitely been a balancing act.

At the same time, I have been able to sustain a lot of momentum with my art-making, and I have the space to fail, which is refreshing. With this program, I have been able to reclaim space for myself within my practice and re-center what is important to me in my practice, which has been fully supported by my program Chair, Chris Fraser.

Since graduating undergrad, I’ve been blessed with a wealth of opportunities to show my work. But it’s also created a deficit in how much time I’ve had to explore ideas without having to create work for something specific. So I’m cherishing this time to explore and experiment. I’m getting back into making sculptural pieces, spending more time on my tapestries and not feeling the need to share every single step of that process. I’ve been holding onto that space of fun for myself before I start to share my new work, which has really helped me stay focused on the process and not the product.

A Movement in Every Direction: Legacies of the Great Migration, co-organized by the Mississippi Museum of Art and the Baltimore Museum of Art, was on view from April 9 – September 11, 2022. The exhibition opens at the Baltimore Museum of Art on October 30, 2022.