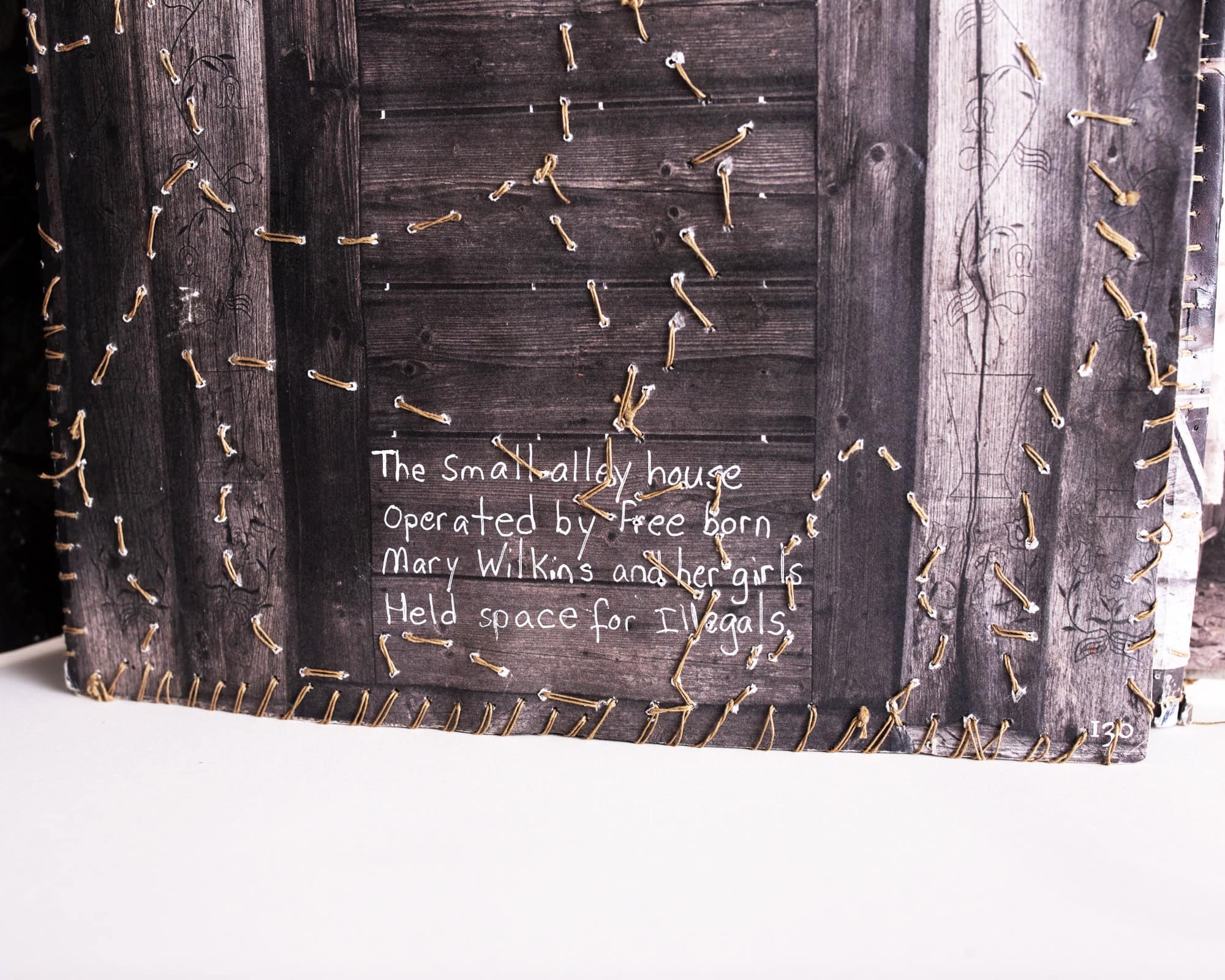

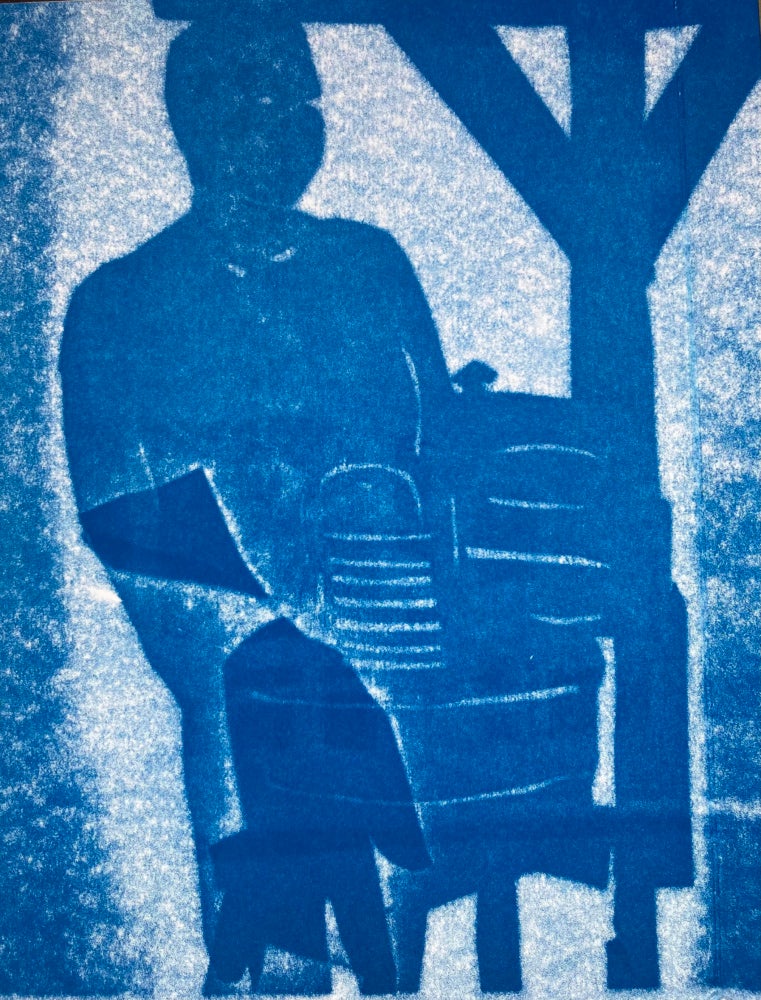

IBé Bulinda Crawley is a book artist and sculptor, as well as a life-long storyteller and educator. Many of her artist books recount stories of Black women who lived in Virginia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. She is a meticulous craftsperson, carefully collecting materials, working them into each book’s structure, and illuminating stories of women who had been silenced by disenfranchisement, sexism, the carceral state, poverty, and time. Sho Creek (2024), her latest book, tells the stories of Black washerwomen in 1850s Richmond who built personal wealth during a time of enslavement.

I talked with Crawley at IBé Arts Institute in Hopewell, Virginia, an arts education and residency space founded by Crawley. The Institute also serves as Crawley’s personal art studio and gallery that showcases her work.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Sommer Browning: It’s really nice to see your work in its own space, all together, and with these other details like the furniture you’ve chosen. It feels like all the parts of you, it feels very whole.

IBé Bulinda Crawley: I feel like this [building] is a sculpture for me because it needed such care. When I [first] walked in it was like all other art projects where you can see all the parts and they’re just lying there. The first time I walked in I was like, wow, this is a powerful space. And over time it’s proven itself to be just that.

SB: What was this space before?

IBC: It was built in 1830 by enslaved men who lived on this plantation [the Eppes plantation]. They built this to be a school for the white males on the plantation. I bought it in 2021 and it had been vacant for about thirty years. During the Civil War, it was part of the hospital system and this plantation was Grant’s headquarters. This was supposed to be one of the best hospitals because Grant was here. I think there’s a lot of energy in this area in terms of my own love of history. And I feel like here with the water, with the land, with the story, with the air, even with the birds, it makes me feel like I’m connected to something.

SB: Is that the James River?

IBC: That’s where the James meets the Appomattox, and then it goes to the Chesapeake.

SB: My child and I recently went to Chippokes State Park just down the way. You can find megalodon teeth there, 20-million-year-old fossils.

IBC: So many spirits have already been here from native people, enslaved people, settlers, explorers. It’s amazing. I lived in Washington D.C., in the city. There were always these tall buildings all around me, and there it was about interacting with people. But here it’s about interacting with nature and that’s new for me.

SB: You use a lot of natural materials in your books and many found materials. How do you choose what materials to use? Is the fact that they are “found” important to you?

IBC: I like paper as a material. When I was introduced to it, I liked that I could make it and that it was so common. But it also fit into my story. People say about enslaved people, Why didn’t they just write fake passes? Well, you got to get paper and you got to have ink. And I just thought, wow, I can make paper, paper is a really valuable thing. When I was a kid, I loved back-to-school. I loved to go shopping for my school supplies. I loved my new box of crayons, the paper, the folders, I love writing my name on them. The materials relate to that too, that feeling of being excited.

We live in a world where people like to record things on their computers. A lot of kids don’t have that same experience with paper. That’s a big deal. Paper is a big deal. It has so many layers of meaning and there’s so many things I can do with it. I can sew on it, I can stitch it, I can collage it, I can draw on it, I can paint it, I can print on it.

And I’m interested in found objects. I’m a junker. I go to a junk shop and I’m always like that cotton! I don’t know what to do with this cotton, but wow, this is interesting. So, I buy it. Or I’ll take a class like a letterpress class and I’ll say, I’m going to make one thing in that class. It may be labels, so I’ll make up a bunch of labels. I’ll do things and collect materials for a project, but I won’t always know what project they’re going to go to or how they’re going to be assembled.

SB: How do you find the stories? Do you have a card catalog of stories, like one day I’m going to get to that one?

IBC: I have that. I do. I have a list of stories. When I’m ready to work on a story, it’s got to be fully fleshed out in my mind. What does it look like visually? How would someone see this? How can I tell [the story] without wearing [the reader] down with so much information? How can I visually provide that information so they can figure it out without me being in the middle of their thinking? How can I represent that story authentically? Not in how I feel about it or what I think about it, but what I see. That’s always a challenge. Growing up and being in school, there was this opposition to the word “I.” The teachers would say, Don’t write in first person. Everything can’t be about you. Everything can’t start with you. That’s impacted my writing, but it also impacts my thinking.

Paper is a big deal. It has so many layers of meaning and there’s so many things I can do with it. I can sew on it, I can stitch it, I can collage it, I can draw on it, I can paint it, I can print on it.

In terms of picking stories, there have been things that I have to deal with immediately. Like George Floyd and [the book] Bearing Witness (2020). I did it in one week because that’s how intense that feeling was for me. I didn’t know what else to do. There was so much. And so every day this was the one thing that I could do. Other stories stay with me for a long time like 63 Women (2024), the story of the women in the Civil Rights Movement. This is the third rendition; every time I do it, it’s different.

That story was like, I’m not done yet. I have something else to say. You haven’t said it the way it needs to be said for me right now. That’s part of that storytelling. And then the other part is that sometimes things just sneak up on me, like Delia Posey [of Mount Vernon] (2021). She wanted her story to be told.

Some Black women [see my work] and they’re like, dang, why it’s all got to be about Black women? Or sometimes men go, well, what about the men? Or white people come in and go, what about white people? And I keep saying, well, it ain’t about none of that. It’s about her. This is her story. So deal with her. How do you interact with her? What is your relationship with her? How do you communicate with her? Where is she in your world, your life? That’s all I’m asking. She came across the ocean. She’s here. How do you engage with her?

As a responsible spirit, I have to gather up as much of the material and form it into something that’s visual that says, look, I am here. This is who I am. This is what I do. And it’s love.

SB: Can we talk more about love and caring and motherhood?

IBC: When I look at the work—and sometimes I like to come in, sit with the work, and listen to it—I think that that’s the part of it that touches me. It just naturally keeps coming back to a caring, loving relationship. I think that’s the thing I want it to be more than anything. And really I think it’s about my mother. I just did some writing and I shared it with my sister and it was about how when we were kids, my mother would come get in the bed with us. I always slept next to the wall. So, I was between my mother and the wall and my sister was on the outside.

I felt safe, super safe. I think that’s the safest I’ve ever felt in my entire life. I am left with that feeling about my mother—being in a warm, safe space. There was this body there and it protected me. I don’t have many other memories like that. When I’m working, I think that’s the feeling that I’m carrying. It just keeps resurfacing. And I am a mother, but I don’t think that that’s the requirement. I think the requirement is to have been born from a woman. Isn’t that powerful? It is not about whether or not you have children or anything. It’s about whether or not you were born from a woman. And everybody had to have that experience.

That mother energy—that’s the load that all of the work has to carry. That’s the standard. I want to be safe. I want you to be safe. Everybody wants that feeling more than being free, more than being wealthy, more than being loved. We want to feel safe, and when we feel safe, we can love.