Lina Tharsing is making a new forest: Her new painting series of the same name explores, through archival photographs from the American Museum of Natural History, the nature of habitat dioramas and their implied constructs. Tharsing has an upcoming solo show at {Poem 88} in September so we conversed—as a remote studio visit of sorts—about her current studio set up, living within an artistic family, and conceptual frameworks that inform her practice.

Rachel Reese: Lina, I’m interested to learn about your studio and studio practice. What is your setup, and how often do you work there? I enjoyed discovering that you are part of an artistic family and all have studios in your home.

Lina Tharsing: My mother and father are both painters with deep connections in the Lexington community. Robert Tharsing, my father, was a painting professor at the University of Kentucky for thirty years, and in 2002 my mother, Ann Tower, opened a gallery bearing her name in downtown Lexington. While I was in college at the University of Kentucky, my parents built two studios and a woodshop behind their Victorian home. After graduating, I needed a studio, and my mother offered to let me share hers while I looked for an affordable space. The three of us found that, while a little cluttered, our shared space allowed us to observe the progress of each others work, and I appreciate their input and feedback. My father and I have also become closer as he has taught me about about the chemistry and behavior of paint, explaining what makes certain colors translucent, and others opaque, differences in drying times, and finishes.

I use my mother’s studio to work on smaller paintings, drawings, and collages. My father’s studio is more spacious and can accommodate the large panels I have been working on recently for the {Poem 88} show in September. I prefer to work for long stretches of time during the day while listening to podcasts like Radiolab or This American Life. Listening to podcasts helps to occupy the part of my brain that [unwittingly] wanders into questions of quality, process, and other issues that distract me from my work.

Most of my research and planning happens long before the brush ever touches the panel. I work from photographs and generally sketch out the entire composition before beginning to paint. Once I begin, the painting takes on its own life. Details emerge and shift, and I let my subconscious or unconscious mind take over.

RR: I notice a lot of source material pinned to your walls. Can you tell me what types of magazines and images you are looking at?

LT: I have always been interested in antique books, anatomical drawings, diagrams, botanical illustrations, Life magazines from the 40s and 50s, encyclopedias, topographical maps, and anything that seeks to explain the nature and science of life. The wall of my studio is filled with found materials interspersed with my own ink blots, screen prints, photographs, drawings, and experiments. These incidental curiosities form a working collage, a layering of ideas.

RR: I’m interested to hear about about your ink blots, especially since you mentioned allowing your unconscious mind to take over your working process. This actually seems counter to my original perceptions of your work, which I was imagining to be a rather logical process.

LT: Most of my painting series begin with a very specific idea and then the imagery develops. The material included on the studio wall is much less logical and methodical. The ink blots, collages, and drawings are a way to keep in touch with the unconscious mind. I think of them as seeds that have the potential to grow into more robust ideas.

RR: What type of photographs do you work with? Do you shoot your photography or source it?

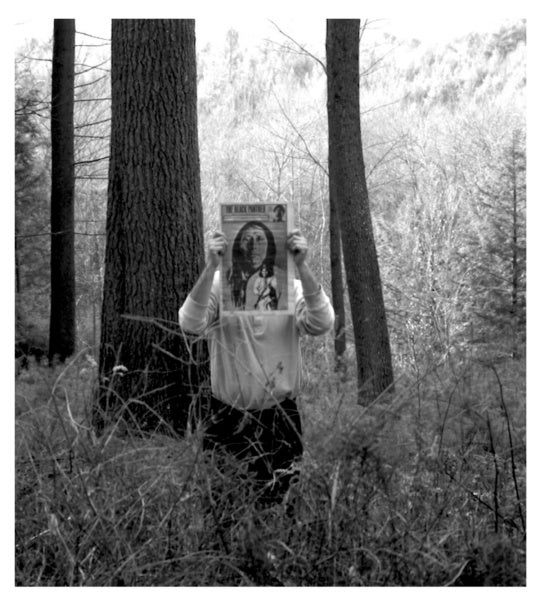

LT: I carry at least two cameras with me wherever I go. I am always looking for the precise moment where the subject seems both real and surreal or magical. I want to find the brightly lit tree in the middle of a forest, or the deep shadow that forms a portal into another dimension. Many of these captured moments become inspiration for paintings. I also incorporate photographic elements like lens flair, over exposure, or flash into my painted work. There is something uncanny about seeing a flash in a painting, because it takes an extra second to process.

RR: I agree. Especially when the execution is precise. When and how did your interest with natural history museums and habitat dioramas develop?

LT: As a child, I was always examining everything around me. I felt somewhat separate from the world but understood that I was part of it, a feeling that led me to think about the nature of reality and the importance of observation. My parents and I spent our summers on a remote island in Nova Scotia, and the days were filled collecting raccoon skulls, porcupine quills, oddly-shaped rocks, bird beaks, nests, moths, and anything that nature had to offer. So many unexpected things wash up on an island shore: part of a wharf, someone’s row boat, a coconut, various hats. Each object has its own mysterious narrative.

I believe that multiple realities can simultaneously exist and that something can be both real and artificial at the same time. Spending each summer on the island, a completely different place from my home in landlocked Kentucky, made it even easier to maintain the dichotomy of real and unreal in my imagination. Kentucky was real. It was where I went to school and carried out my daily routine. Nova Scotia was a lucid dream of islands, pine trees, and specimens. A few years ago I started drawing rooms with windows displaying different environments, thinking that they could be perceived both as windows to an exterior space, or windows into a further contained interior. I was trying to create a visual metaphor but realized that I was, in fact, drawing a diorama.

RR: There is such a strong connection between nature and directed observation. In doing some of my own research lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the scope with regards to observation and the history of rifles as scopic devices. That to really observe something, we had to kill it, and then bring it back to “life” again through the habitat diorama.

LT: You bring up an interesting idea of the rifle with its scope being used as an instrument to both observe and kill. Your point touches on two ideas I thought about while making these paintings: The first being that the camera is always capturing a moment that is now dead and gone. The other is that these natural history museums serve as extensive documentation of a world that is disappearing. They are freezing time and place. My recent exhibition at the University of Kentucky Hospital is titled Making A New Forest because the natural history museum serves as a surrogate for the actual environment. We can travel across continents without leaving a building.

RR: And the habitat diorama, as an artificial construct, is a form that is itself a scopic model with a fixed observation point—

LT: One of the defining charachteristics of a diorama is the inherent eerie stillness and silence. Dioramas are closer to photographs because they capture a moment that has ceased to exist in the outside world.

RR: Your current paintings from Making a New Forest are painted in greyscale. What drove the decision to remove your color palette as in prior works? How does the greyscale function conceptually for you?

LT: The paintings in my most recent series are based on archived images from the American Museum of Natural History. The photographs that documented the creation of those dioramas are, of course, black and white. The first paintings I made were small watercolors of those images using an imagined color palette, but they never looked convincing. I decided to experiment with painting them as they appeared and became fascinated by the process of transcribing a black and white photograph into a black and white painting.

Photography feels very “real” to us still, despite our common knowledge of the existence of Photoshop and other image altering technologies. It has a rich, almost inescapable, history of documentation. Photographic images always seem to be telling the truth. Painting on the other hand, no matter how realistic, is always symbolic. We are intensely aware of the artist’s hand. Translating these archived images into paintings poses many more questions than the original photographs do. The interactions between the men in their lab coats and the animals take on new meaning.

RR: I really enjoy your awareness and inclusion of the scientists painting the diorama backgrounds. A critical visual point in the diorama is the meeting of the sculptured scene and the painted backdrop, which opens the conversation to a discussion of illusion. I have been re-reading an essay by Magnus Bärtås recently about this exact topic, in which he quotes:

“The viewer of a nature diorama should not have his attention caught by such materialism; it should instead travel as if through infinite space, a reflecting space with a source in the daylight that a real nature diorama should be created for. The reflecting space or the optical boundlessness should arise via an exact and precise management of the painting of the diorama’s domed wall.”

Are you conceptually upending this notion? How do you work with framing devices in your compositions? Framing (and observation/scopic devices) are particularly important aspects of habitat dioramas.

LT: In order to make a painting of a diorama, you have to reveal its structure; otherwise it would simply look like a painting of a landscape. Artists like Hiroshi Sugimoto have photographed dioramas in such a way as to make them appear more realistic by cropping out the frame of the window. I’m interested in showing the reflections in the glass, the lights, and the curve of the painted wall behind the animals. In this most recent series, I wanted to push that even further by including the people who built and painted the dioramas.

RR: It looks like there is a new body of work in your studio. I see ceremonial masks and what appear to be traditional costuming in a few of the paintings. Tell me about those!

LT: The unfinished painting with the costumes is related to the same body of work [Making A New Forest], because it’s also based on an archived image from the American Museum of Natural History. The next series of paintings will be a departure from the natural history museum as a subject; instead, I’d like to make a few large paintings based on my own color photographs, similar to the smaller version of the Paint Factory.

RR: I’d like to hear about the Paint Factory—both the painting and the physical location. Where was this and how did you discover the building?

LT: The Paint Factory was an abandoned warehouse in Atlanta that had been given new life by graffiti artists. Every wall was covered with spray paint. I wandered into the deepest part of the old factory, and saw the ceiling had caved in, but the way it had collapsed looked almost like an installation. The scene embodied the tension I always look for. The image was both real and unreal, haphazard and composed.

RR: Can you briefly talk about your upcoming show at {Poem 88} this fall?

LT: I’m excited about showing my work in Atlanta. I’ve visited the city many times and have been impressed by the art scene. I really appreciate Robin [Bernat] giving me this opportunity to show at her gallery, {Poem 88}, which has a strong following, and rich exhibition history. The show at {Poem 88} will be an extension of an exhibition currently on display at the University of Kentucky Chandler Hospital.

Lina Tharsing is a Kentucky-based artist whose work has been shown across the Southeastern United States. In 2012, she was named a superstar of Southern art by Oxford American. Her most recent shows have been Natural History at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, Natural History II at Conduit Gallery in Dallas, Texas and Making a New Forest at the University of Kentucky Chandler Hospital. She has been featured in Whitehot Magazine and RadioLab’s blog. Tharsing graduated with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Kentucky in 2007.

House rules for commenting:

1. Please use a full first name. We do not support hiding behind anonymity.

2. All comments on BURNAWAY are moderated. Please be patient—we’ll do our best to keep up, but sometimes it may take us a bit to get to all of them.

3. BURNAWAY reserves the right to refuse or reject comments.

4. We support critically engaged arguments (both positive and negative), but please don’t be a jerk, ok? Comments should never be personally offensive in nature.