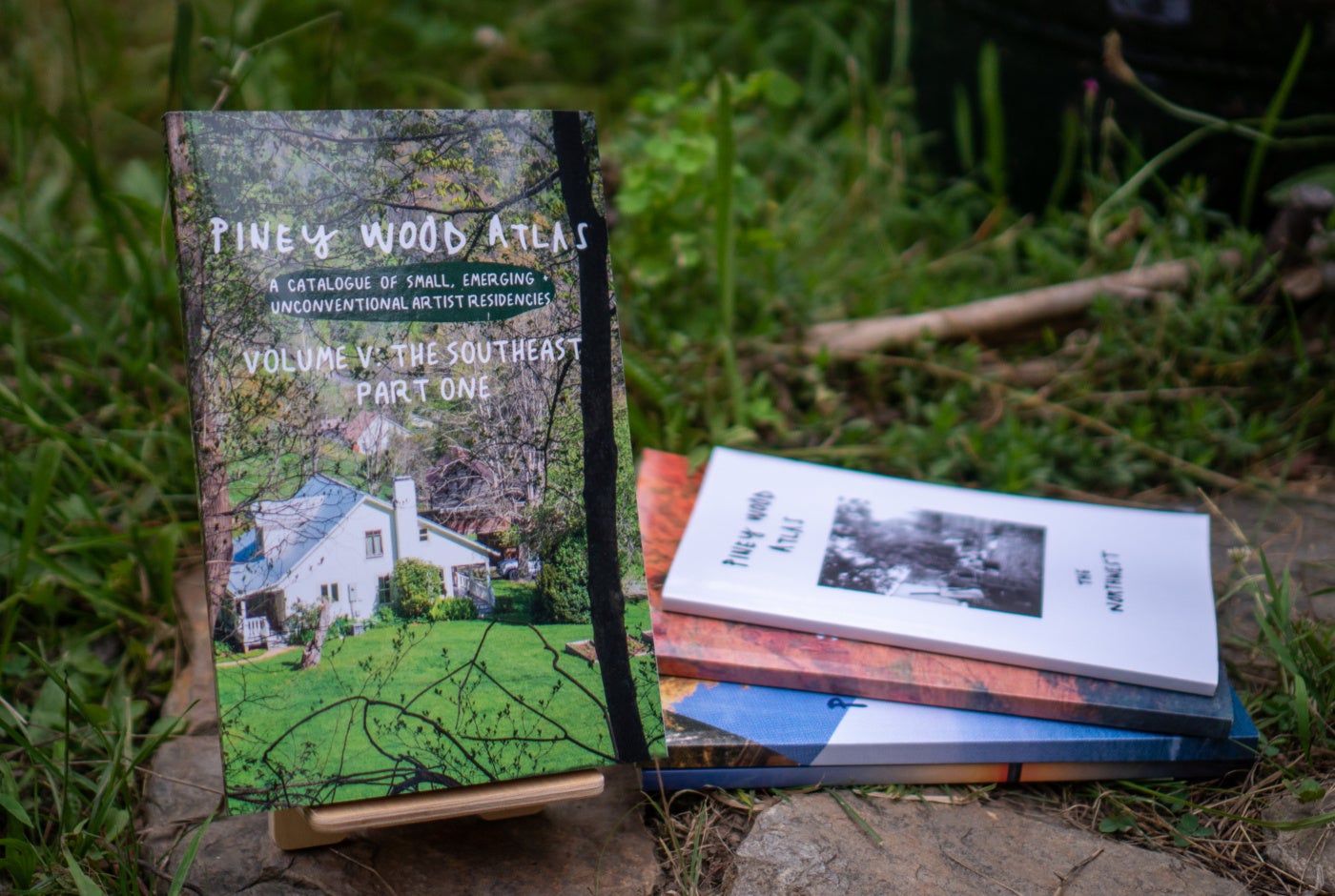

Piney Wood Atlas is a collaborative residency research project formed by two artists, Carolina Porras Monroy and Alicia Toldi, after fortuitously meeting at a small, rural residency in western Colorado.

Through a series of road trips, we visit small, emerging, and unconventional artist residencies—alternative residencies compared to the large, established ones that may be more well-known. By spending time at these residencies, touring the spaces, interviewing facilitators and artists, often sharing meals and spending the night, we get a feel and understanding for each space. Our experiences at these locations are translated into a book format, full of profiles for each residency, contributions from friends in the field, and fun stops along the way. This year, we published our fifth book, the first of two that will cover the Southeastern United States.

We are inspired by unique aspects of the residencies and regions we are visiting—some kind of general spirit that starts to emerge after exploring and engaging with our new environment. On our latest adventure visiting six residencies in Florida and Louisiana, one of three trips across the Southeast, we decided to record a conversation musing on what we’ve seen throughout the region. Taking a back road on the long drive down to the tip of Florida to visit a residency embedded in Everglades National Park, we hit record on our cellphone as we made our way.

Carolina Porras Monroy: We are currently in the car, driving alongside Lake Okeechobee, which is framed by a levee and a canal. There’s a lot of palm trees, farms, Spanish moss, and flatlands. We just saw a roadkill alligator, which was our first alligator of the trip…sad. [Update: we soon saw several beautiful living alligators in the Everglades.]

Alicia Toldi: What were you just saying about the spirit of Southern residencies?

CPM: So I think with the South, including our trip to Texas, and now Louisiana and Florida, we have heard a lot from communities trying to resist the negative perception of the South that it’s all super conservative and everyone there has bad views on LGBTQ rights or education… But there are so many communities out here that are resisting that stereotype and creating spaces for artists.

AT: And not only resisting, but also working with those communities and finding common ground and not being too judgmental…and then also making very important work that does resist that stuff. I think about Erin Elizabeth Smith from Sundress Academy for the Arts in Tennessee talking about how Appalachian hollers were originally places and still are places where people can just be themselves and not be witnessed. And have that safe space, whether they’re making moonshine or being queer, or just having a private life.

CPM: And Shoog MacDaniel from Hazey Acres also mentioned a similar idea in their corner of rural North Florida. I feel rural spaces in general have a reputation of being unsafe for queer people and people of color. But we have found many rural spaces in the South that are super welcoming for those communities, and it is mixed with people who maybe have more conservative views. Those are the things that I’ve found to be special about Southern spaces— not to mention, the natural landscape here is so fascinating. Visiting ACA Soundscape Field Station Residency at the Canaveral National Seashore, and Hazey Acres too, highlighted the uniqueness of the landscape here in Florida.

AT: Yeah. I’m also thinking about how in a lot of places in the South, building a creative space may be a little more affordable than in other parts of the country. There seem to be a lot of historic buildings that it is possible to purchase or use for not very much if you’re willing to put in some work. The facilitators of Volatile House in Montezuma, GA, bought a Queen Anne Victorian mansion for $69,900 on Cheap Old Houses. Their project exemplifies just how amazing it is to turn a decrepit unused space into a residency. Which we’ve seen in other regions too, like the Wedding Cake House in Providence, RI, and elsewhere.

I think there’s a lot of that here. Another example is Aquarium Gallery & Studios in New Orleans, which had to be completely fixed up when Jacob Reptile bought it, because it had no roof. But a roofless house in San Francisco… that wouldn’t exist, you know? There’s a strong DIY spirit here, and the materials and locations to make it happen.

CPM: Yeah, there’s a level of scrappiness and community effort, which, again, does exist in other areas…

AT: But it’s like an element of life here, a notable element. Last year, we visited On::View Residency at ARTS Southeast in Savannah, GA, which is another example of that. The landlord couldn’t use this space with a bunch of tiny rooms in it, and then allowed this group of artists he hardly knew to exist in the space until he could find someone to rent it, and he never did, and then they ended up buying it from him. That’s amazing. And ACA Soundcape Field Station, the residency at Canaveral National Seashore is housed in what was until recently an unused national park building, originally the home of a pioneering strong woman who lived there before it was a park. The partnership between the Atlantic Center for the Arts and the park service allows this awesome historical building to be utilized by sound artists, not just sitting there empty.

CPM: I’m also thinking about when we visited Flower Shop Residency in Brownsville, TX, right on the border of the United States and Mexico and just about all the current political climate with the Trump administration and deportation. It’s all so scary and violent, but also there are people who live in those border towns who are doing some really cool, amazing things to advocate for their communities.

AT: Yeah. I think there’s something there, too, about how people are thriving and existing while at the same time being threatened.

CPM: Yes. And in a similar way, when we visited A Studio in the Woods in New Orleans, LA, they mentioned that they’re “on the frontlines of climate change.” The bottomland hardwood forest the residency space exists in is changing before their very eyes due to the above-average rate of environmental impact in southern Louisiana. Also, Katrina is a huge marker of time for the residencies we visited in Louisiana. So much changed after that natural disaster and the way that this country dealt with it, or lacked thereof. And the receding shorelines of Florida… I’m just thinking about how these Southern areas are really on the frontlines.

AT: Both politically and environmentally. This makes me think of the permaculture concept of “edge zones,” the liminal space where two ecosystems meet. These places are more diverse and full of life due to the exchange that happens there and the unique species that crop up for this very reason. On the other hand, a monocrop is an unstable, unhealthy system that is more likely to collapse. To create a healthy ecosystem, you need as much variety as possible. ACA Soundscape Field Station is located in a literal edge zone between the subtropical and the temperate, which provides artists with a fertile landscape to draw inspiration from and work with on environmental art. But then also, if the edge is political or cultural, such as a border or a place with a lot of political differences? It’s similarly a fertile zone for art making.

Learn more about Piney Wood Atlas and the residencies mentioned at www.pineywoodatlas.com or @pineywoodatlas. Book 5, addressing residencies in the northern half of the Southeast, is now available and Book 6, covering Texas to Florida along the Gulf Coast, will be released in early 2026.

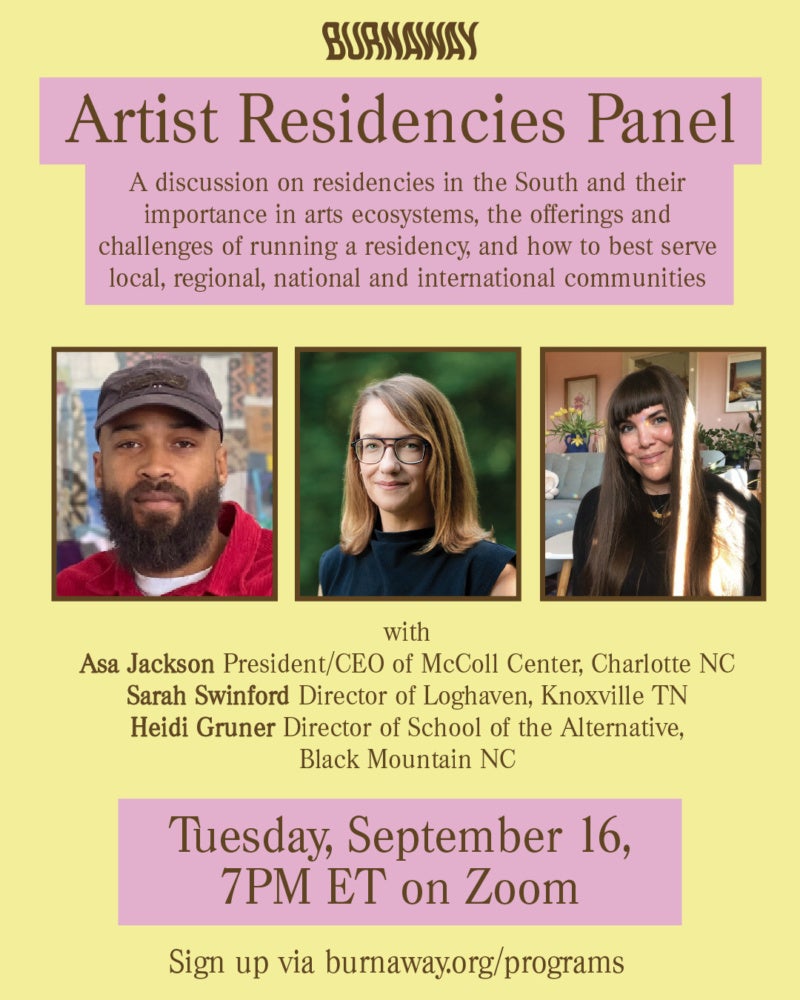

Join Burnaway on Tuesday, September 16 at 7PM ET for a virtual panel on artist residencies in the South. Our Editor and Artistic Director Courtney McClellan will be moderating a conversation between Asa Jackson, President/CEO of McColl Center, Sarah Swinford, Director of Loghaven, and Heidi Gruner, Director of School of the Alternative. We’ll hear about what it’s like to run artist residencies in the South, their importance in arts ecosystems, the offerings and challenges of running a residency, and how to best serve local, regional, national, and international communities. They’ll also discuss what it’s like to bring artists from around the world to the South.