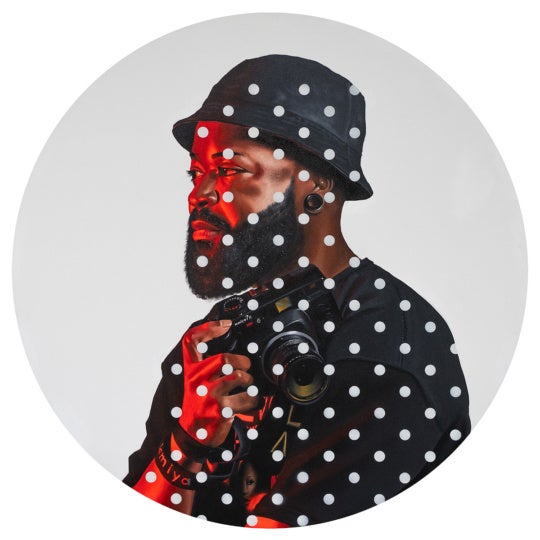

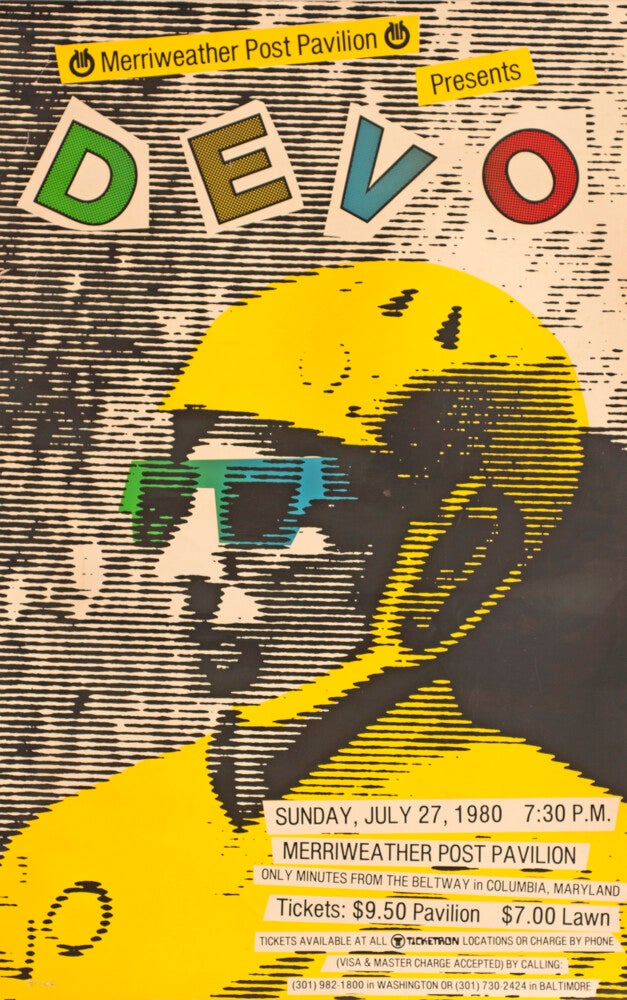

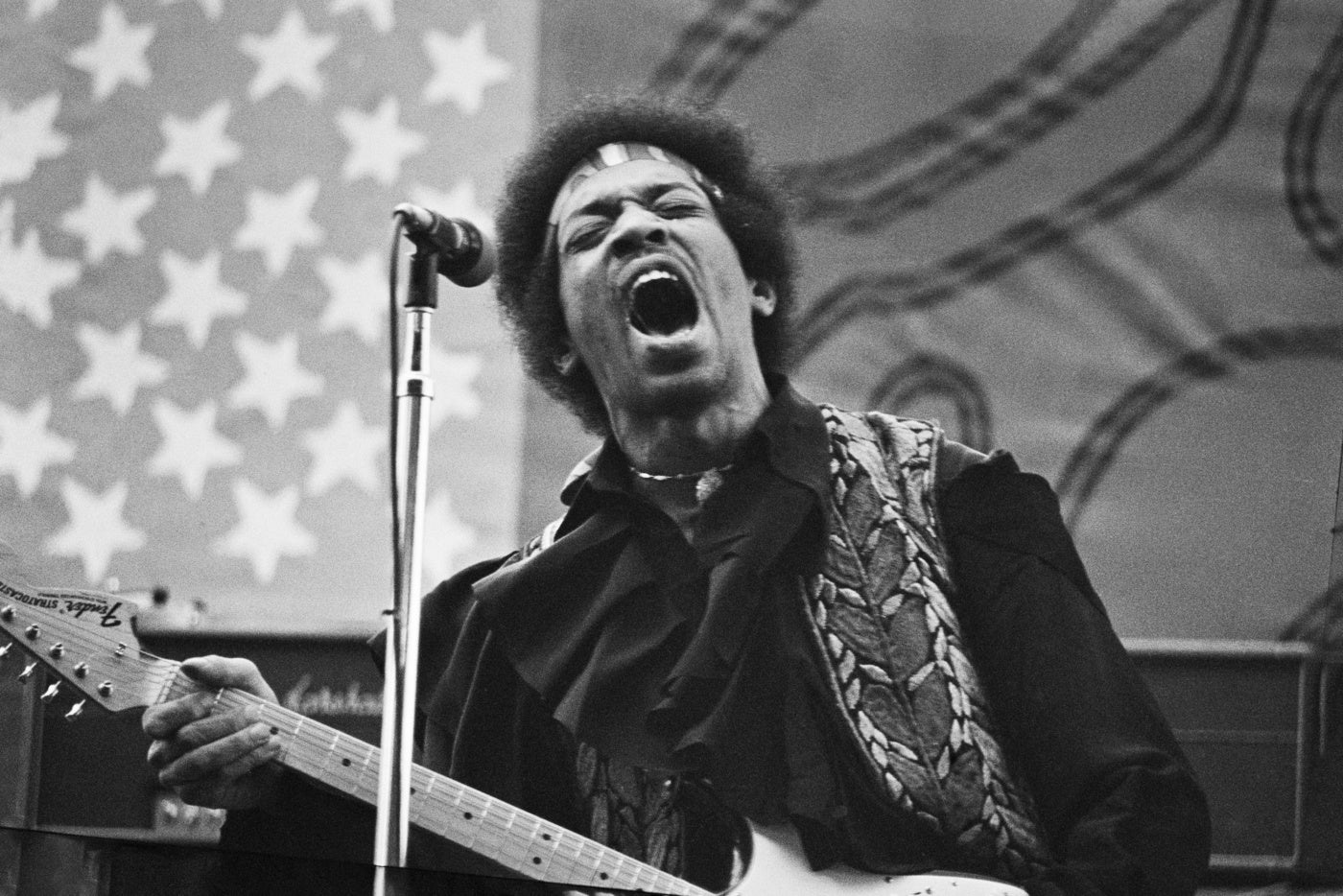

The Orlando Museum of Art (OMA) is currently presenting a trifecta of exhibitions on subcultures. Push addresses skateboarding through J. Grant Brittain’s black and white photographs of the California skate scene in the 80s, which saw the rise of skateboarding legend Tony Hawk. Torn Apart: Punk + New Wave Graphics, Fashion, and Culture, 1976 – 1986 includes punk posters, graphics, music, fashion, and images captured by Punk photographer Sheila Rock. Front Row Center is a traveling exhibition, which features icons of Rock, Blues, and Soul music taken by concert photographer Larry Hurst.

Upon the occasion of these shows, I met with OMA’s Chief Curator, Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon to talk about how images and objects of youth culture are becoming artifacts that help to keep the arts alive.

Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Zeny May Recidoro: What prompted the exhibitions on popular subcultures like Push, Torn Apart, Front Row Center to be shown at the Orlando Museum of Art?

Coralie Claeysen-Gleyzon: There’s a key word in there, subcultures. Skateboarding photography, or skateboarding as a culture, and the Punk scene have been seen, well, they’ve been presented as subcultures or alternative cultures. There’s always something a little negative in the idea of subcultures or counterculture but there’s people for whom it’s their main culture. Something that I’ve been wanting to do with the museum for a long time is to serve new and other audiences, and especially audiences that belong to parallel fields or perspectives. People already know that Punk has an incredible design [aesthetic], and so I’ve always been interested in drawing the parallels and bringing those audiences into the museum. At the same time, it’s also about reconfiguring and rethinking the museum.

Now, I also think that Orlando is a key place to actually make that happen. Orlando is a city that’s still very young. It’s like a teenage city, and still trying to find itself. It’s surrounded by entertainment. So people are, by nature, really open minded about what they see. There’s a term in French called bon vivant, which means, happy to live. All these elements are the perfect incubator, or the perfect environment for exhibitions like these to be well received. It’s also validating for some cultures because it’s about representation. I truly believe that with making museums more accessible (or relatable), there’s a way we learn about each other.

Orlando is a city that’s still very young. It’s like a teenage city, and still trying to find itself.

How it was prompted to be shown at OMA: the collector of the objects shown in Torn Apart (Andrew Krevine) called me one day and said, ‘I have this beautiful collection, the biggest collection of Punk posters in the world. And I think you’d really like it.” I was already thinking about how we connect to the tech audiences, the design audiences, the fashion audiences that are creatives, but don’t necessarily come to a traditional art museum or art exhibit. So I was just on the phone with him, and I told him, ‘Why don’t you send me some pictures and we’ll look?’ He sent me pictures of his collection, and I was blown away. I saw incredible designs and connections to art history. When you dig in a little bit, you find that so many Punk bands had members that had been to art school. There are interconnections throughout.

ZMR: I think it’s true that Orlando is a teenage city, but like many things about this place, there’s something more to it. Sub or counter-cultures in Central Florida are tied to people’s sense of locality. There is also a sense for the fantastic and folklore more than cultural affinities, like Punk, Rock n’ Roll, or a skater lifestyle or youth culture in general. Ironically, I think this makes the feel or psyche of Orlando seem outside-of-time or young. It’s constantly transforming its identity. Given this context, how did you work on the programming?

CCG: We try to have exhibitions as diverse as possible, so there’s something for almost everyone. The three exhibitions are connected through nostalgia. So it’s, you have these cross generational connections that happen and they strike a chord in people. It’s about what they remember, their memories, shared and handed down. The other three have the same effect. If you look at Larry Hurst’s photography of the 70s to the 90s Rock n’ Roll, Blues, and Soul music scene, it connects to the emotions of music and so many iconic moments on stage that he photographed, and people would say, ‘I was at that concert.’ That happened as well with Torn Apart, where people say, ‘That was my bedroom wall.’ We had so many comments like that, you know, where the public comes in and say, ‘If you take this section, that was my bedroom wall,’ or ‘You know, I had The Clash posters’, ‘I had New Order or Joy Division’, and so it’s actually really wonderful to hear the connections, and to have people come back.

ZMR: It’s interesting that you mentioned nostalgia, because I was thinking about the shows and its common theme being youth culture. It pertains to being young and belligerent but these icons and objects of youth culture, by being shown in museums, are also being turned into artifacts.

CCG: What I find with these exhibitions is that art, as a way of being, is still alive. Art is alive. If we just leave an object in a case, it loses its magic, it loses its aura and its power. And so I’m actually actively working towards changing that kind of rethinking of this place, rethinking, and again, it’s looking back at what a museum in the twenty-first century should be.

ZMR: It’s also interesting to me how these three exhibits establish a really good sense of placeness and temporality with image and sound. It works with how you curated the space to hold these photographs, posters, and memorabilia from specific eras in Punk and Rock n’ Roll. What I thought about, especially with Torn Apart, was that it really felt like a punk teen’s bedroom. I think that was a clever way to curate. How much of your personal experiences and preferences inform your affinity for creating these shows?

CCG: When you have affinities with things, it helps you see the value of certain things. However, I was never a punk, you know, I didn’t live through the Punk Era. The show is co-curated with another curator who is a lot closer to the Punk Era than I am, Michael Worthington, and so all of us wrote essays for the catalog. Well, I couldn’t pretend to be a punk, to have lived through it. But what I knew was the importance of putting on shows like these and museums and what they do, and what you know, what the audiences it serves, and what we can learn from it.

ZMR: I also noticed that Torn Apart and Front Row Center are auditory. They’re very sound based. But when you get to Push, it’s very quiet. I could almost hear the sound of the skateboard wheels on asphalt and concrete. It’s image and space at work. What informed the curatorial choices around image and sound?

CCG: When you look at what J. Grant Brittain did is very similar to what Sheila Rock did. He was there. He was managing the Del Mar skate [park] at the time and was a skater and surfer. He was a self-taught photographer with a borrowed camera that captured the skateboarding and surfing scenes. I love when we give tours to youth. We ask them, ‘How would you capture the scene around you today?’ We’re encouraging them to think in that way, and to also value their contributions. Without Sheila Rock or J. Grant Brittain, all those scenes may not have been noticed as much as they are today. Tony Hawk may not be who he is today.

ZMR: What is your favorite image among the exhibits?

CCG: In the J. Grant Brittain exhibition, Push, I loved The Homage to Christo (1985). It’s funny and it’s tongue-in-cheek. The skateboard is wrapped just like a human, it’s a wonderful portrait, it gives it a presence and the composition is beautiful. It’s also personal. I first saw a Christo artwork when I was nine years old, my mother bought this art book and I saw one of his artworks in it. And it changed my idea and understanding of what art is and could be. If I look at Torn Apart, it’s not just one artwork but whole walls, on women in Punk and activism in Punk. It’s my favorite because it shows how Punk pushed boundaries and [intended to be] inclusive. The scene was very gender neutral and you can see that the clothing was unisex. Which was punks partly wanting to protest and to be provocative by being progressive.

Push: J. Grant Brittain 80s Skateboarding Photography and Front Row Center is on view at the Orlando Museum of Art until January 5, 2025. Torn Apart: Punk + New Wave Graphics, Fashion, and Culture, 1976 – 1986 is on view until February 2, 2025.