Despite a censorship hiccup that garnered national attention, the Zuckerman Museum of Art (ZMA) at Kennesaw State University is off to a promising start with the exhibitions “See Through Walls” and “Salon Wall Selections,” both on view through April 26. The museum’s new 9,300-square-foot, glass-clad building houses breezy galleries and outdoor space. With the additional space, the ZMA plans to rotate works from its approximately 6,000-piece permanent collection, while remaining current by exhibiting works by local and nationally recognized contemporary artists. It is a wonderful development, especially in Atlanta, where new museums are rarely built. The museum, just 20 miles north of Midtown Atlanta, had a well-attended grand opening on March 1, with about 1,700 visitors, some of whom showed their support of censored artist Ruth Stanford by wearing signs or T-shirts, and others who ignored the protestors or were unaware of the incident. The contested work, A Walk in the Valley, is now back on view, and extensive explanatory materials are available at the front desk. The two inaugural exhibitions feed off each other; “Salon Wall Selections,” a salon-style hanging of diverse works from the collection, features artists who are also in “See Through Walls,” which is curated by ZMA director of curatorial affairs Teresa Bramlette Reeves and associate curator Kirstie Tepper.

The outdoor Upper Pavilion will be used for movie screenings, outdoor events, and additional installation space. Lauri Stallings of gloATL choreographed dance pieces specifically for the architectural parameters. Rabideau, who is also an artist, sees the new space as a big positive for the Atlanta art scene stating, “I believe that the Zuckerman Museum of Art has a unique opportunity to create a dynamic artistic experience . . . through commissioned work, challenging exhibitions, and meaningful educational outreach.” There is a need for more spaces that fall between a commercial gallery, which must survive on sales, and a museum, which tend to be less flexible, less contemporary, and have fewer exhibitions. The ZMA could be the perfect addition to the city’s two main venues: the High Museum of Art and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center. The shows together consider the concept of space in a variety of ways, most vividly in how the tangible location informs the artworks themselves. The artists in “See Through Walls” examine real and imagined environments. They dig deep to find the power of location that affects people daily on an emotional and personal level. A strong architectural bent runs through the show and references the new building itself, beginning with the most simplistic of architectural devices: a wall. In Breaking Ground, created by members of the Zuckerman’s architectural firm Stanley Beaman & Sears, actual topographical information from the new building’s site has been utilized to form a catawumpus grid on the exterior of the wall panel. Installed in the stairwell, it is the first of a series of year-long commissions for that space.

In the chalkboard wall drawing As black as this board, biracial artist Bethany Joy Collins turns racially inflected language—in this case Paula Dean’s—that she navigates on a daily basis into dim highways of text. The piece manages to express subconscious recollections, the nexus of what is personal and what is cultural, manifold explanations, and the duality of perception, all in a cloud of chalkboard dust. One of my favorite works in the show is by Adriane Colburn, whom I had the opportunity to speak with over the phone. The artist was originally asked to comment on West Texas oil and fracking operations for an exhibition put together by Ballroom Marfa. Her piece is composed of photographs that she took when a pilot gave her an aerial tour in a small airplane of Midland/Odessa, Texas, combined with images from Google Earth. The collection of images, strung together with strands of Mylar, also includes mixed-media elements of ink, acrylic paint and postcards. Colburn excised all natural elements from the visuals to reinforce the presence of the human hand. She considers landscape to be “the contemporary sublime”—the sublime being a sense of awe. She feels that because of technology the world around us resonates in different ways for human beings. She wanted to document the infrastructure that we utilize every day but don’t really see. Her installation has more of an element of allure than any sharp political focus.

Cheryl Goldsleger’s, two paintings on linen, Academy and Azimuth, stem more from a researcher’s state of mind than an artistic one. Goldsleger began this work in 2009 at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., and her interest was sparked by the original building’s design by American architect Bertram Goodhue. Her detailed drawings on canvas of architectural structures, with their sharp edges and straight lines, seem an expanse away from some of the more figural works presented in “Salon Wall Selections.” I was able to take an imaginary tour of the building while viewing the works. Goldsleger compares her drawings to a “researcher’s notes,” and I could feel the metaphorical propinquity of her practice to the structure she had investigated. Another highlight from this cleverly curated show was Casey Lynch’s Parergon (2013). This sizable installation of LED lights, hanging canvas, drywall, wood, wire, and Plexiglas creates its own corner in the gallery and stretches between and sometimes frames other works in the gallery. French philosopher Jacques Derrida defined the parergon as an object that acts as a border separating an artwork from its surroundings, a frame. The perimeter of the work held equal importance in Derrida’s eyes. Lynch uses light as a tool to facilitate his own philosophical posture as he ponders questions about one’s existence, the creative spirit, a renewable world, and the ways in which society will use its forthcoming theories and scientific knowledge. The curators pulled in a heavyweight with a work by Gordon Matta-Clark. His seminal film Splitting (1974) shows the artist practicing what he called Anarchitecture, in which he divides and makes cuts in houses with a power saw, as a critique of the structure or fixed order of society.

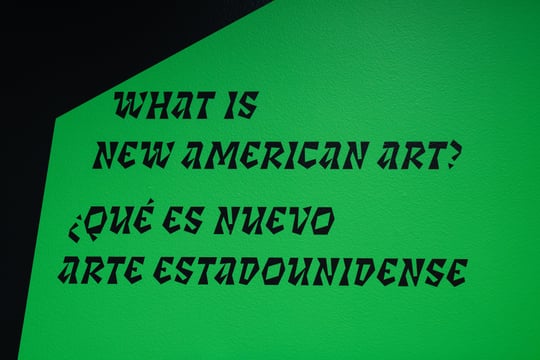

Imi Hwangbo’s Spire serves as a sort of gateway drug into the “Salon Wall Selections” show. The hand-cut Mylar piece from 2004 draws on 19th-century Korean wrapping cloths called pojagi and the chrysanthemum patterns that festooned them. Hwangbo, who teaches at the University of Georgia, has created a series of three-dimensional drawings based on the traditional symbols associated with pojagi of a powerful and uncultivated territory. The hand-cut Mylar is layered in a way that builds Spire into an emblem of its own, that of man’s desire to draw from the land such sacred attributes as fruitfulness and durability. “In “Salon Wall Selections,” the works are hung salon style, from floor to ceiling, the entire wall brimming with art. What held my interest here is the inspired drawing from long-established practices for displaying exhibitions, which encourages viewers to have a discourse with one another about the art. This detailed attention to place forms the theoretical bridge to the exhibition “See Through Walls.” There are numerous American artists, as well as those from such places as Russia, Scotland, and Israeli. There are ivory works from Mangbetu/Azande Democratic Republic of the Congo. The show proves unconventional in its inclusion of newer works, like Ben Goldman’s video Worker (2013) and Casey Lynch’s piece Space.Craft. (2014). Other artists included on the salon wall include Collins, Goldsleger, Jenene Nagy, and Stanley Beaman & Sears. The darkish blue color for the walls was chosen because it is a verifiable shade that could have been seen in a 19th-century French salon. During my time in this particular “salon,” I discovered history reinterpreted.

Reeves explains: “the Salon style hanging is meant to evoke the idea of a gathering of art objects and patrons for ongoing conversations and dialogue about art.” She adds “the juxtaposition of historical and contemporary works and media foreshadows our desire to contextualize work of all types from all periods, thus adding depth to each. We are working to remove the historical barriers between different kinds of objects and approaches.” So what will be the ZMA’s ultimate connection to the Atlanta arts scene? Kennesaw State University was determined to make an adventurous landmark through innovative architecture. Next up at the ZMA is “The Second Annual Walthall Fellowship” exhibition, May 17-July 5, in collaboration with WonderRoot. Artists will include Jessica Caldas, Christopher Chambers, Aubrey Longley-Cook, Antonio Darden, Alex Gallo-Brown, Heather Greenway, Iman Person, Myrna Prochuck, Nathan Sharratt, Julie Sims, Onur Topul-Sumer, and Jonathan Welsh. In the next year of programming, the museum will include a retrospective of the modernist works of Georgia-born artist Virginia Dudley (1913-1981), a show exploring curatorial visions mixing the history of different plants with sound installation, an exhibition titled “Hearsay” that will focus on the act of a game similar to Telephone , and will feature projects by John Q, Adam Doskey, Carolyn Carr, Nikita Gale, George Long, and Robert Sherer.

The Zuckerman may not be located inside the perimeter, but it’s taking the Metro area to cutting-edge places.

There will be a panel discussion with artists, curators, and architects on April 12, called “Considering Spaces.”

Sherri Caudell, a poet and writer from Atlanta, is the new poetry editor of Loose Change magazine, published by WonderRoot.