Nashville art lovers are not immune to the election anxiety gripping the nation. We may not feel gripped, exactly. Maybe it’s more like a barely perceptible electric current that spontaneously zaps us each time we go online to check our e-mail or post some pics of our reclaimed barnwood coffee tables. And when I say “we,” I mean our often politically complacent art scene. Ours is an overwhelmingly polite community where collaboration thrives and — with few exceptions — criticism is handled with kid gloves. Bless her heart and all that.

So imagine my surprise when I heard about the Trump art show at Gallery Luperca, a newish gallery on the east side owned by KT Wolf and Sara Lederach. Curated by Robert Scobey, “Trumped Up” had the potential to engage the Nashville art scene beyond its usual limits, but in many ways, it falls short.

In large part, the artists of “Trumped Up” address the theme from a place of comfort, as if they are sharing a secret that most of America just doesn’t understand. About half of the artists included are from Tennessee. It is worth noting that neither the curator nor the gallerist knew whether any people of color replied to the call for artists. This isn’t unusual in Nashville, but it seems particularly irresponsible given the theme of the show.

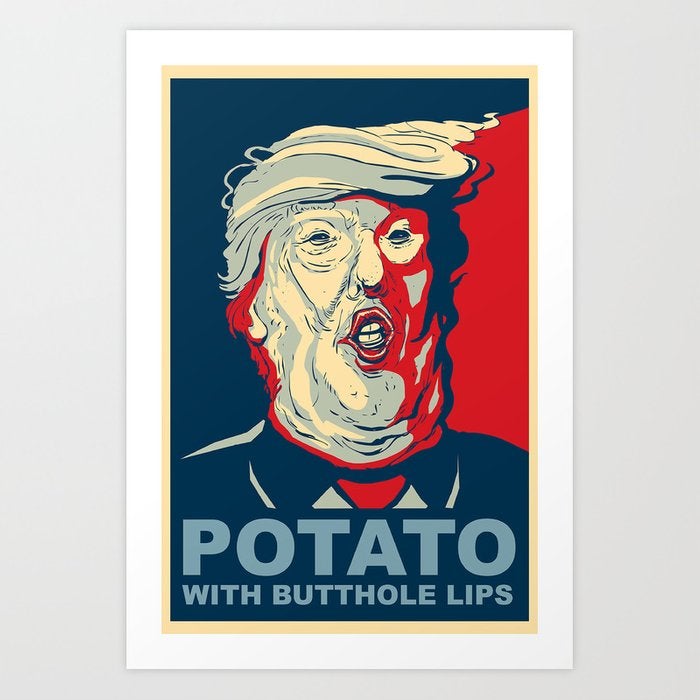

Dusty Peterson’s riff on the iconic Shepard Fairey poster shows Trump as fat-faced and wrinkly, with rolls of flesh puddling around his neck. In place of “hope,” block letters read, “Potato with Butthole Lips.”

Scobey’s untitled short film, which he lists as being authored by The Internet, is a picture montage set to “Songbird” by Kenny G. If you’re looking for a chance to see all the images from Trump memes in succession set to the tune of smooth white jazz, this is it. Alex Lockwood’s Donald Trump Mask fits into his oeuvre; made from plastic and silicone, his pink-cheeked Trump has mac-n-cheese hair and squinting, white-lidded eyes.

Also included is Phillip Kremer’s oft-Instagrammed photographic manipulation of a mansplaining Trump, mulletted and noseless, called Banger. There’s also an illustrated Trump dick, a papier-mâché mask, a sculpture of an ape wearing a bowtie, and portraits that render him with machine guns, a Donald Duck bill, and with more than a few orange strands of hair glued in a smear on his face.

With a few exceptions, the work in “Trumped Up” misses the mark by focusing on the spectacle of Trump — his hair, his body, the unnatural color of his skin — instead of providing meaningful commentary on the white supremacist culture, institutions, and policy that have nurtured his platform and supporters for centuries. While the spectacle of Trump can be seen as emblematic of white America’s lack of empathy for people with disabilities and people of color — black, Latino, immigrant, Muslim, Asian, American Indian — it is not in itself a meaningful critique. The show may be well-intentioned, but unfortunately, it reads as shallow and ineffectual.

Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle may offer some context to the aims of the show. In his 1967 book, Debord argues that authentic social life has been replaced by disembodied representations — phony, commodified, and consumer-driven. The French philosopher may have prophesied our modern age, where social media has become a stand-in for social interactions and reality television becomes more “real” than the lives of those around us. Much has been written about the alienating nature of contemporary social interactions and celebrity obsession — and perhaps Trump is a fitting symbol. Essentially, Debord argues that our relationships are reduced by images that define how we related to one another. Debord called for us to be awakened from our drugged, image-saturated states. Does “Trumped Up” accomplish this? Does it ask us to take a step back from our consumer-driven art world and ponder the cost of our obsession with spectacle?

A few pieces do. Megan Foster‘s video Artifice disguises a critique of Trump’s misogyny in the form of a retro movie trailer rife with footage of Trump and clips from Russ Meyer’s 1970s films. Foster smartly shows the violence of Trump’s misogyny by couching the critique in the language and images of sexploitation. The result is a fun minute and a half that lays plain Trump’s exploitation of white America’s fears.

In Scobey’s second piece, Donald J. Trump National Park and Resorts System, the artist blew up a map of our national parks, recreation centers, scenic trails, etc., and renamed them for the real estate mogul, making visible the privatization of public resources. Donald J. Trump Knife River Indian Village and Donald J. Trump Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site point to the historical whitewashing that’s widely promoted by the GOP. Anna Nichol Stutsman’s It’s What’s Under the Hood… is a white klansmanesque hood smeared with self-tanner. Though Stutsman’s piece is a bit too on the nose, it addresses the legacy of white supremacy that has created Trump. Is his spray tan the new mask of white supremacy, and will his rise result in contemporary lynchings?

This is not to say that an artistic rendering of Trump cannot be political. After Australian-American artist lllma Gore’s pastel nude of Trump went viral, she was threatened and attacked by some of his supporters. There is real risked involved in criticizing the demagogue. But the central problem that contemporary art indeed has the power to address is this: focusing on the man himself allows us the moral high ground to denounce Trump and his supporters. The spectacle of Trump is a comfortable means of criticism for white Americans and indeed for white artists. The orange face, the hair, the jowls, this subtracts from the substantive criticism in Stutsman, Foster, and Scobey’s work.

One piece might save “Trumped Up” from itself. In Ugly American, George Lorio mirrors two United States-shaped wood cutouts: Washington touching Washington, Maine touching Maine. One is painted like the good old American flag. The other is painted in the flag’s negative colors, green, black, and orange. Between them sits a wooden heart that’s plastered with shredded dollar bills.

While we white liberals mock and jeer at the other America, the one that we don’t invite into our art galleries, the one that so offends our moral sensibilities, the one whose open and explicit racism allows us to hide behind our own, to what extent does that America prop us up? To what extent does Trump’s America allow us to keep our side of the street clean?

There’s a question I’d like to see artists answer.