For collectors of rare and out-of-print books on art, architecture, design and photography, R.W. Smith Bookseller has been an esteemed go-to source ever since it was first established in 1975 in New Haven, Connecticut. The owner, Raymond Smith, is also a familiar name in literary and academic circles for his writings on art, photography, and literature. But now, another of his talents is attracting major attention and acclaim. Since the 2014 publication of In Time We Shall Know Ourselves: American Photographs, 1974, a black-and-white portfolio of 52 prints, Smith has emerged as an artist who, in the tradition of Walker Evans and Robert Frank, reveals the state of the nation through its people and places.

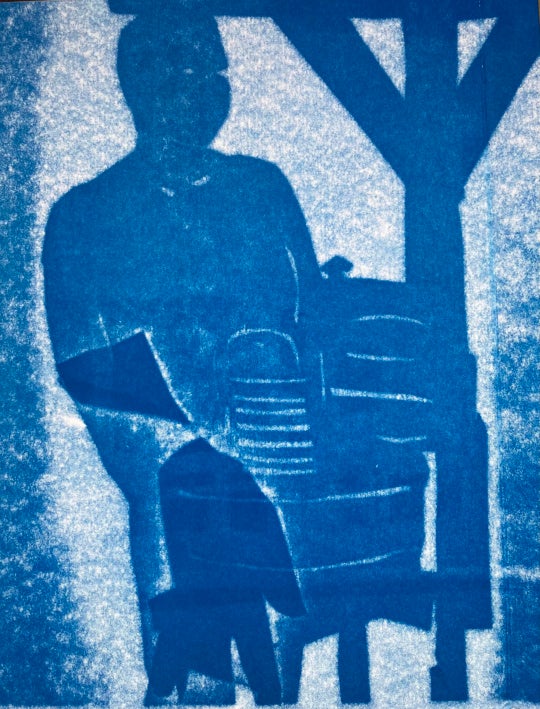

The comparisons are apt, because Smith has acknowledged both men as major influences. In fact, Smith studied under Evans when he was in the graduate program in American Studies at Yale University in 1971-72. And the photographs featured in In Time We Shall Know Ourselves was the result of a 1974 trek across America that visits some of the same places Frank immortalized in his classic 1959 photo collection The Americans. Despite this, Smith’s work stands apart from these two iconic masters of the form, revealing a style of his own that vividly reflects a personal approach to portraiture and, in Smith’s words, “the American vernacular landscape.”

Currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art through January 3, “In Time We Shall Know Ourselves” is a carefully considered showcase of his work, which incorporates illuminating comments from the artist and authors Richard King (A Southern Renaissance: The Cultural Awakening of the American South) and Alexander Nemerov (Soulmaker: The Times of Lewis Hine) into the accompanying descriptions. As for the title of the book and the exhibition, they were inspired by a phrase on a roadside sign that Smith saw near Hattiesburg, Mississippi.

All of the photographs are silver gelatin prints and, in one display case, you can see the Rolleiflex he used on his cross-country journey; he also used a Minolta, another twin-lens reflex camera. Using both increased his flexibility in shooting and experimenting with shutter speeds.

Bus Stop, from Car Window, Houston, Texas and Union Station, Kansas City both represent Smith’s exploration of shooting from a moving car with the focus set on infinity. The photographs may seem haphazard on first impression, but they also contain a spontaneous quality that captures the look and feel of a specific urban landscape with people frozen in the frame at that moment in time.

Much more typical of Smith’s work are the portraits of people he met on his travels in July-September of 1974, when the country was going through a major transition period: President Nixon resigned in August and the Vietnam war would officially end the following spring, after the fall of Saigon to South Vietnamese forces. This time frame is interesting to consider when you gaze at portraits taken in Columbus, Texas; Demopolis, Alabama, or Sandusky, Ohio, all of them mirroring the reality of their subjects and their specific environment (home, work, streets, yards, etc.).

Fotomat Girl, Louisville, Kentucky is unusually striking with the subject gazing directly at the camera from the type of pop-up photo booths that were prevalent in shopping center parking lots in the ’70s. The composition does not feel staged or contrived and is distinguished by its fascinating detail (a customer in the background car, the big print signage, the concise framing of the subject in an almost hermetically sealed space) that transforms what could have been mundane into something haunting and unforgettable. Street Corner Preacher, Savannah, Georgia and Outside Volcelka’s Bar, Omaha, Nebraska are compelling examples in the same vein. Both capture the subjects in their own social milieu, posing comfortably without affectation. “They seem to be saying this is how I prepare myself to be seen. It is just what I’m “like” is how art scholar Richard King describes it in one annotation.

Several group portraits are on display as well, and these also have a purity and authenticity that offer intimate windows into lives often overlooked or unnoticed in America’s heartland. Among some of the more outstanding examples are Men on Front Porch, Kansas City; Boys in Parked Car, Meridian, Mississippi and Caregiver and Children, Savannah, Georgia. In all of these, the subjects are no less important than the main protagonists in novels and suggest intriguing backstories based on their appearance. Smith even confirms this in one caption, stating that, “Photography, for me, is more closely related to literature … than it is to other visual arts. Whether the location is a city sidewalk, a backyard, a roadside or a door front, for me the portrait is primary, and the photograph is a short story exploding beyond its frame.”

Smith’s “short story” analogy about his images doesn’t always apply as easily to nonhuman subjects, such as American Flag, Midland, Pennsylvania or Burial Ground, St. Andrews Episcopal Church, Hale County, Alabama. The viewer has to work much harder to extract meaning or understand Smith’s viewpoint of these seemingly random rural images, which would be much less evocative if exhibited separately or outside the context of this show. But a much more revealing example of a still life is Rural Highway, Southern Georgia, After Rainstorm which shows Smith’s VW parked on the shoulder of a deserted highway with the passenger door open. A closer inspection reveals a background sign “Christ is the Answer” glimpsed in the background through the passenger door window. It is indicative of the sense of discovery and subtle detail that usually informs any Smith composition the viewer cares to contemplate.

“In Time We Shall Know Ourselves” has been on tour at museum exhibitions in Alabama, North Carolina, and Florida, before its final stop at the Georgia Museum of Art. For anyone interested in the medium of photography, Smith’s work is one of those unexpected revelations that suddenly surface years after the work was initially completed, much like the photographs of the once-obscure Vivian Maier. (Few of Smith’s 1974 prints had been seen or exhibited until the appearance of his published portfolio last year). The 52 images only whet your appetite to see more and perhaps a future exhibition may be curated from the 750 or so exposures Smith took during that initial road trip 41 years ago.

“In Time We Shall Know Ourselves: Photographs by Raymond Smith” is on view at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens through January 3. It will appear at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, June 1-September 18, 2016.

Jeff Stafford writes about art, film, music, gardening and other favorite topics for various digital publications.