“This Postman Collects: The Rapture of Kerry and C. Betty Davis,” the aptly named exhibition on view at Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries through July 1 is a celebration of African American art and of the twin joys of collecting and connection to community. Tina Dunkley, guest curator and former director of CAU Art Galleries, selected 80 works from the Davises’ prodigious collection in an exhibition that educates, awes, and delights. [Listen to our StoryCorps interview with Dunkley.]

Included are well-known artists Jacob Lawrence, Elizabeth Catlett and Romare Bearden, local artists such as Larry Walker, Bennie Andrews, Louis Delsarte and Freddie Styles, and works by some lesser known but equally compelling artists in works that range from landscapes and portraiture to narrative, abstraction, and the sociopolitical — impressive work, individually and collectively, made even more compelling by the fact that the Davises have amassed their collection on the middle-class salaries of a postman and television producer. That they have done so with such an earnest dedication to the task, generosity to the community and, above all, as the title conveys, a joyous spirit, is what makes their collection so uniquely inspiring as well.

Kerry Davis worked for 30 years as a postman, delivering mail in downtown Atlanta in a route that included Georgia State University, where he met Dunkley, who served then as that university’s gallery director. In her essay for the exhibition’s illuminating catalogue, she evokes the similar story of Dorothy and Herbert Vogel, who built their collection of over 5,000 works of Minimalist and Conceptual art on the salaries of a librarian and postman and later donated it to the National Gallery of Art. Comparisons are inevitable, but the Davises’ vision, which has been shaped by a fine tradition of African American art collectors who believed in the importance of gathering and preserving the legacy of African American artists, owes much, not to the Vogels’ influence but to a century’s worth of important African American collectors ranging from Alain LeRoy Locke, dean of the Harlem Renaissance and author of the 1925 seminal article “The Legacy of Ancestral Arts,” which called upon African American artists to draw inspiration from traditional African designs rather than the tenets of European art, and Lillian Evans Tibbs, who like Locke was associated with Howard University, and whose home, like the Davises’, became an informal art gallery and salon for many of that city’s artists and intellectuals. Closer to home, the influence of Atlanta University’s Hale Woodruff, who in 1942 founded the university’s annual “Exhibition of Paintings, Prints and Sculpture by Negro Artists in America,” is inestimable. (Don’t miss his magnificent murals outside the galleries.)

Davis, in conversation in the galleries with. Dunkley on February 4, charmed his audience with humor, modesty, and stories of his nascent desire to collect and the influence of others before him. Though he had been collecting before they were married, the couple set out together as newlyweds with no more than the simple desire to furnish their new home with vibrant art that gave them pleasure. Their pleasure, it seems, has become the good fortune of us all.

Growing up in Atlanta, Davis recounted, he didn’t know anyone who collected art, admitting that it “wasn’t until The Cosby Show premiered on television in the 1980s that he had ever seen any black people with art in their homes.” In addition to his visits to the university galleries that seeded his interest as well as his knowledge, his job as postman provided opportunities for visits with his postal customers, some of whom collected art, and to educate himself (sometimes with other people’s catalogues and magazines) in the larger world of collecting. A flyer meant for a postal patron directed him to his first auction where he unfurled the contents of an unopened mailing tube and walked away with his first important purchase: My God is a Rock, a linocut by Charles White from 1958, whose powerful presence is now central to the collection that has grown over the years to 300 works which hang salon-style in the Davises’ suburban Atlanta home. The collectors, friends, and neighbors who have been the Davises’ delighted guests over the years have dubbed their collection an “In-Home Museum.”

Davis found his introduction to African American art in well-known artists Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden. Lawrence’s serigraph Toussaint L’Ouverture, 1986, on view here, was an early purchase. From there, he reported in an earlier interview with Dunkley, he “just kind of explored the contemporaries of Lawrence and Bearden and people in their circle,” but soon looked farther afield for others – and closer to home. The exhibition catalogue for the David Driskell-curated “Two Centuries of Black American Art” at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1976 opened Davis’s eyes to many different artists and, with that, he was off and running.

To educate himself, he frequented local gallery collections, particularly those of Spelman and CAU, by then under Dunkley’s stewardship. He sought out small auctions – the ones, he said without a drop of condescension, “that wouldn’t know a Jacob Lawrence from a Jacob’s Ladder!” and traveled to the hometowns of artists he was interested in to see what he could turn up. The Davises befriended local artists who, in turn, introduced them to other artists. Larry and Brenda Thompson, ardent collectors and arts philanthropists, who provided support for this exhibition, recall in their introduction to the catalogue that Styles brought Kerry Davis to a party and introduced him as “ a postman who had one of the best collections of African American art in Atlanta.” Indeed.

The Davises are such delightful people, and their story so satisfying that their rapture, the sheer joy with which they have collected, could almost have been the point of the exhibition – and in a lesser collection, it just might have been. Here, albeit in some more than others, there are rapturous moments to be found in every single piece.

Charles White’s etching Lilly C, made at the end of his life in 1973 and Norman Morgan’s Harriet Tubman, a hand-colored engraving from 2002 in which the abolitionist looks up from the bottom of a ravine are good examples. A mother’s fierce, protective love is reflected in Elizabeth Catlett’s bronze Mother and Child from 1980, and Ernest Crichlow’s lithograph Waiting shows a lone child peering through a barbed wire fence, an image made even more moving by its date of 1968, a time of so much turmoil and disillusionment. But no work speaks more powerfully or with more gravitas than the Civil War veteran in Edward A. Harlestons’s A Colored Grand Army Man. In this pastel portrait from 1925, the 80-year-old Smart Chisholm, a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, is dressed in the uniform he wore 60 years earlier and stares right into the future with a look of unyielding pride and immeasurable sadness. His gaze will linger long after you leave the gallery, as it should.

Some selections are quieter, like the delicate winter light in John Hardwick’s undated landscape or Michael Morgan’s untitled watercolor depicting the silent isolation of a family on a moving train. Some are humorous and some bold. Richard Mayhew’s untitled watercolor from 2006, in deep purples, greens, and yellows, is one of Betty Davis’s favorites. Alma Thomas’s untitled watercolor in bright blue is another.

Works by Hale Woodruff, Romare Bearden, Beverly Buchannan and Radcliffe Bailey are more recognizable, while others, like a mixed-media painting by Eric Mack, seem brand new. As varied and eclectic as the collection may be, it is united by the Davises’ eye for what they love.

The work isn’t hung chronologically. It isn’t hung thematically. It isn’t grouped by style or medium — though most of the sculpture is grouped together — and there is no pattern to be discerned, but the installation is entirely pleasing and seemingly as if it could be no other way. So what criteria guided Dunkley’s choice and display of 80 works from the Davises’ 300 in the galleries? Gallery director Maurita Poole delivered what should have been the obvious answer: “Tina Dunkley is an artist herself. She is a musician and a singer, a sculptor. She loves jazz, syncopation, improvisation. Just look at those diagonals, the way the corners of one relate to the corners of its neighbor. It’s perfect.” And so it is – artist-designed, the only way it could be.

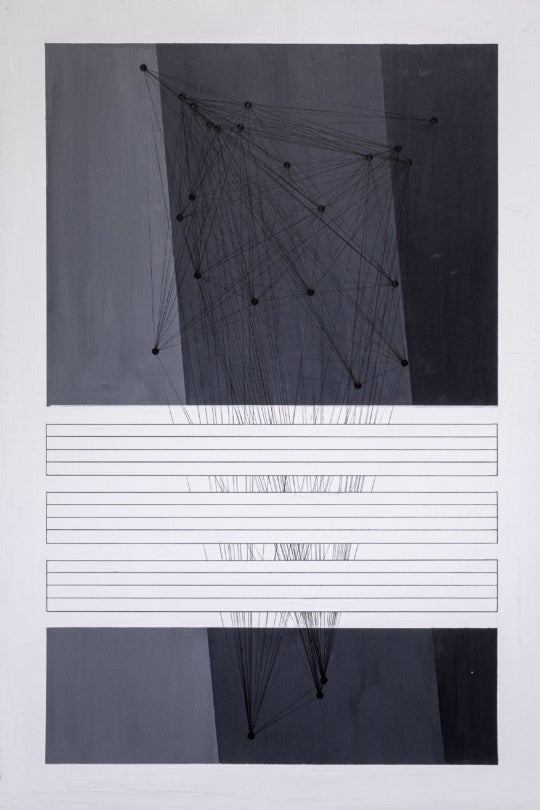

Kerry Davis, in conversation that evening with Dunkley, recounted a moment he shared with the great Mildred Thompson, whose works are standouts in the exhibition. She encouraged him to contact other artists, and when he expressed nervousness at the thought of contacting a particular artist he feared was “too important, too great” to bother, Thompson replied, “Then he ain’t that great; greatness is always accessible.”

It is a description that seems tailor-made for the unassuming and accessible Kerry Davis, who together with his wife C. Betty Davis, have positioned themselves, as Dunkley writes in her catalogue essay, as “stewards of community cultural memory.”

Donna Mintz is an Atlanta-based visual artist who also writes about art.