I went to see This is America*—a group show on view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum in Lexington—on a particularly cold and gray Tuesday in early January when the campus was still empty of students. At the entrance to the gallery, sheets of plywood nailed to the wall introduced the show’s title in red spray paint, the materials an all-too familiar reminder of the protests that have inflamed our nation’s cities over the past year. Below, a smaller piece of plywood announced an equally grim statistic: the current total of COVID deaths in the U.S., updated each week by the museum director. I showed my timed tickets to the masked attendant and had my temperature checked; it all felt slightly heavy.

The next day, as a pro-Trump mob stormed the Capitol, an already weighty show suddenly felt like lead. Originally intended to coincide with the 2020 presidential election, This is America* had already taken on additional significance (and works) in the midst of the ongoing pandemic and protests. With the opening delayed, its curator dedicated the exhibition to the late John Lewis, the U.S. Congressman who had spent his career fighting for civil rights.

This unreconciled gulf between the American ideals of liberty and equality and the harsh reality of its legacy is brought into stark relief with the first pairing of works: Gilbert Stuart’s Portrait of George Washington hangs next to Michael Wong’s George Floyd: Blackout Tuesday, a reverse time lapse video in which the artist’s sketch of the murder victim slowly emerges from a black square, his death yet another asterisk on our country’s troubled historical record.

Similar juxtapositions abound. Sheldon Tapley’s Midwestern Alley—a quiet, suburban pastoral—depicts a different America than the one experienced by Black figures in Elliot Erwitt’s gelatin silver print Segregated Water Fountains, North Carolina. Andy Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians (Sitting Bull) finds itself neighbor to a text work by Kay Rosen that proclaims MY LAND LAND MINE. Wendy Bolton Rowland’s ceramic Crucifixion is mounted above Ruin by Mel Chin, in which the artist has taken American currency—perhaps representing the true religion of our nation—and erased most of its elements until only a few broken columns remain, the ruins of a fallen civilization.

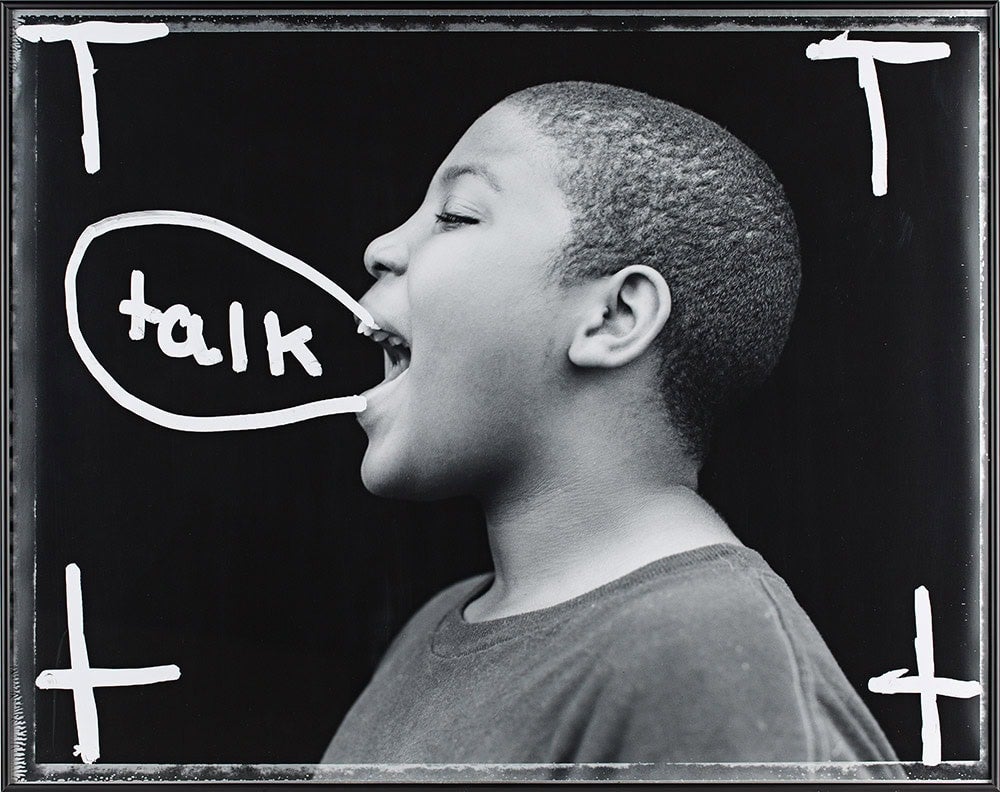

Four works from Jon Henry’s Stranger Fruit series offer moving portraits of Black mothers posed with their sons in configurations that recall pietà sculptures. Photographed in front of urban streets and government buildings, the families become public memorials to contemporary mothers’ pain and anguish. On the floor below sits a piece by Louis Zoellar Bickett: a small granite slab incised with the text There were 353 documented lynchings that occurred in Kentucky. Rendered in capital letters and a plain typeface, the statement assumes a flatness that, combined with the work’s unassuming position on the floor, creates an understated effect that is at odds with the shocking and horrifying disclosure. Both Henry and Bickett’s works provide an alternative narrative to the thousands of public monuments across the U.S. that celebrate white achievement (so often at the expense of Black compatriots).

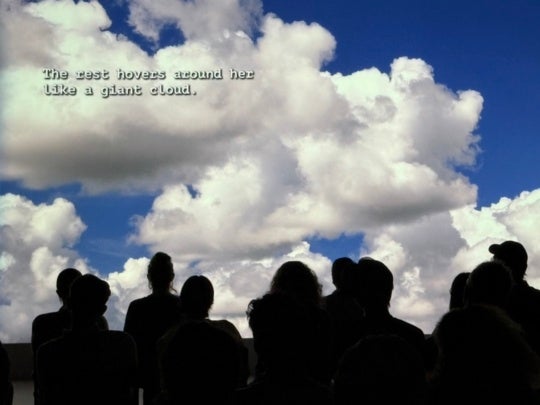

One of the most powerful works in the show is a large-scale painting by Mike Howard titled Charlottesville A Crime Scene, which depicts the 2017 attack in which a young white American deliberately drove his car through a crowd peacefully protesting a white supremacist rally. A muted palette dominated by the soft grey shades of the car and asphalt and the gentle blue-green skies lends an unsettling quietness to the scene. Hurried brushstrokes bring an immediacy to the work and suggest a desire to capture what the artist recognizes as an important moment in American history and imbue it with a significance not granted by our twenty-four-hour news-cycle culture.

This is America* does skew toward the male, both in artists represented and in subjects depicted. But somehow, it feels appropriate. It looks like the America where I was raised: where men dominated board rooms, newsrooms, and government offices. And within the show, this bias actually serves to amplify the power of a work like A DRESS/Address: What They Asked: Christine Blasey Ford. On a white neoprene trench coat, artists Alix Pearlstein and Suzanne McClelland printed the questions posed to Ford during Senate hearings designed to discredit her accusations of sexual assault against Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh. Isolated in the middle of the gallery, the work alludes to the continued assault on the female body by the patriarchy.

The exhibition also tends to favor Southern artists and subject matter, which is understandable given its geographical context and that it draws heavily on works in the university’s significant collection. But then again, telling the story of America, in fact, requires telling the story of the South—of the slaves who enabled our country’s growth, of the Civil War and all its atrocities, of the lynchings and bombings and police shootings in all the decades that followed. Yet despite the South’s role as an active participant in some of the worst asterisks on our national record, it has also been the site of reconciliation and hope. As Black author Z.Z. Packer, who grew up in Atlanta and Louisville, wrote in 2008:

“We also can’t forget that the solution to the problem—the sit-ins, the marches, the hope of better days—began in the South as well … And as backward as we’ve been portrayed … the truth is that every awful and beautiful thing that has happened in America happened in the South first.”

Indeed, This is America* reflects on a lot of awful things that have happened in our country’s history, some of them very recently. But it also speaks to the artists’ refusal to look away—to their persistent need to not only critically engage with national issues that spark conflict and violence, but also to challenge our assumptions about ideas like identity, justice and freedom. In so doing, artists open up the space for ambiguity, complexity, nuance, and, yes, even beauty.

This is America* is on view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum in Lexington, Kentucky through February 13, 2021.