As a little girl exploring downtown San Francisco, my father would implore me to match his quick gait, saying, “Keep up, or you’ll get run over–and don’t make eye contact.” The one time he would break this informal code of the streets was when he’d nod to another Black man or woman offering a quick “Hello,” or, “How ya doin’?’’ Then, he would quickly resume pace. That nod would become a welcome sign of acceptance within spaces where I felt anything but. In those moments, “the nod” made me feel seen.

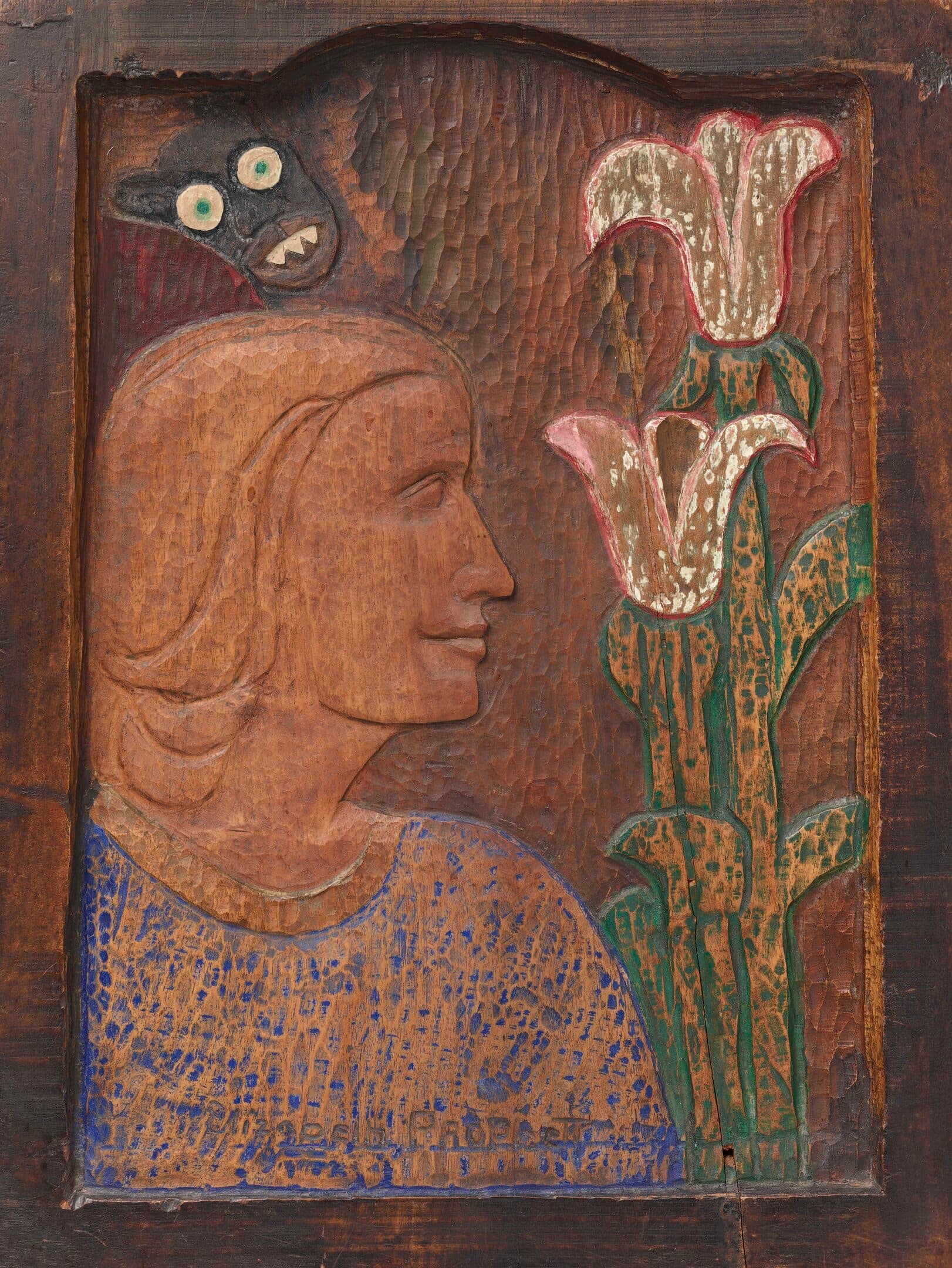

There are times when art becomes that gesture, a moment where our presence is acknowledged, free from hypervisibility or hostile invisibility. With the traveling exhibition The Time is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure, currently at the North Carolina Museum of Art, British curator Ekow Eshun presents work from twenty three African diasporic artists who render Black subjectivity, identity, and interiority while subverting notions of the gaze.

Three pillars within the show support a framework grounded in Western Black literary thought: Double Consciousness, Past and Presence: the Pursuit of History, and Aliveness. These are states of being that Black folk traverse, mediating the space between our actualized selves and a perception of our being which is constantly shaped by influences that distort, enhance, or reinforce those perceptions.

The title comes from James Baldwin’s 1956 essay titled Faulkner and Desegregation, in which Baldwin examines the psychology of white southern resistance during the fight for Civil Rights in the mid-century—an analysis which remains disturbingly relevant seventy years later. The exhibition, now in its third and final iteration in North Carolina, takes on a particular poignance in a climate characterized by fear, and uncertainty as institutions navigate the onslaught of re-segregationist rhetoric and anti–Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion directives that force a pointed return to Baldwin’s scrutiny: “There is never time in the future in which we will work out our salvation. The challenge is in the moment, the time is always now.”[1] More broadly, this show challenges the Western art canon by addressing its erasure of the Black body in art history; it also corrects the systemic exclusion of Black artists across the diaspora who are underrepresented within the permanent collections of our cultural institutions.

The first of the three pillars in the show, Double Consciousness, refers to the concept introduced by W.E.B. Du Bois in 1897, describing a racial hierarchy where Blackness is defined through and conscripted into whiteness. “It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.”[2] Here, Du Bois introduces the veil: the physical separation between how we are perceived by dominant society versus how we see ourselves. This severance dismisses and erases Blackness as it extracts and repackages it.

Rope Chain (2021) by Lorna Simpson is Double Consciousness personified—a collage of a Black woman wearing a black felt hat and a thick, gold braided chain, a throwback to 1980s hip-hop regality. The piece reveals a bifurcated persona, between an imagined and reimagined identity awash in a blue veil. Nathaniel Mary Quinn employs a more surrealist, chaotic approach to his collaged paintings, replete with complicated compositions. In Homeboy Down the Block (2018), a painted melange of eyes, lips, and noses explore the multifaceted refractions of double consciousness. Similarly, a nine-foot-tall gilded bronze sculpture of a Black woman by British sculptor Thomas J Price towers over the gallery [As Sound Turns to Noise (2023)]—she is an amalgamation of physical features and character traits the artist observed while conducting a series of interviews with Black women in the streets of Los Angeles.

These collaged constructions are surrounded by a variety of portraits of women at rest, men at play, children in mourning, and partiers reveling, all demonstrating the luscious complexity of Black life beyond the veil. Within the show, curator Ekow Eshun strategically placed works that offer historical insights into how the veil wove its way into art history.

In Past and Presence: the Persistence of History, Eshun presents artists who explore world making through the prism of memory, imploring what writer Kevin A. Blanks notes, “as we imagine a Black world of life for us, we must lift the veil, become whole, and carry the memory of the past with us always.”[3] Artists including Titus Kaphar and Barbara Walker play with visibility, invisibility, and memory in their juxtapositions with the past, placing Black subjects who were once relegated to the conceptual margins of the frame to the center. Here, the depth of field is made wider, as artists and historians highlight these once unknown subjects, contextualizing their utility and the erasure of their humanity.

And on the other side of that reckoning with the past, a painting by Kerry James Marshall features an artist painting their self-portrait, placing their likeness squarely in the center of the narrative, veil removed, both halves merged into one [Untitled (Painter), (2009)]. The painting, featured in Marshall’s 2017 retrospective Mastry, embodies this pinnacle of excellence, as he described: “Mastry means that one is able to self-determine how one wants to be represented, how one wants to be seen.”

“We are not the idea of us, we are not even the idea that we hold of us. We are just us, multiple and varied, becoming. The heterogeneity of us. Blackness in a black world is everything, which means it gets to be freed from being any one thing. We are ordinary beauty, black people, and beauty must be allowed to do its beautiful, ordinary work.” Kevin Quashie[4]

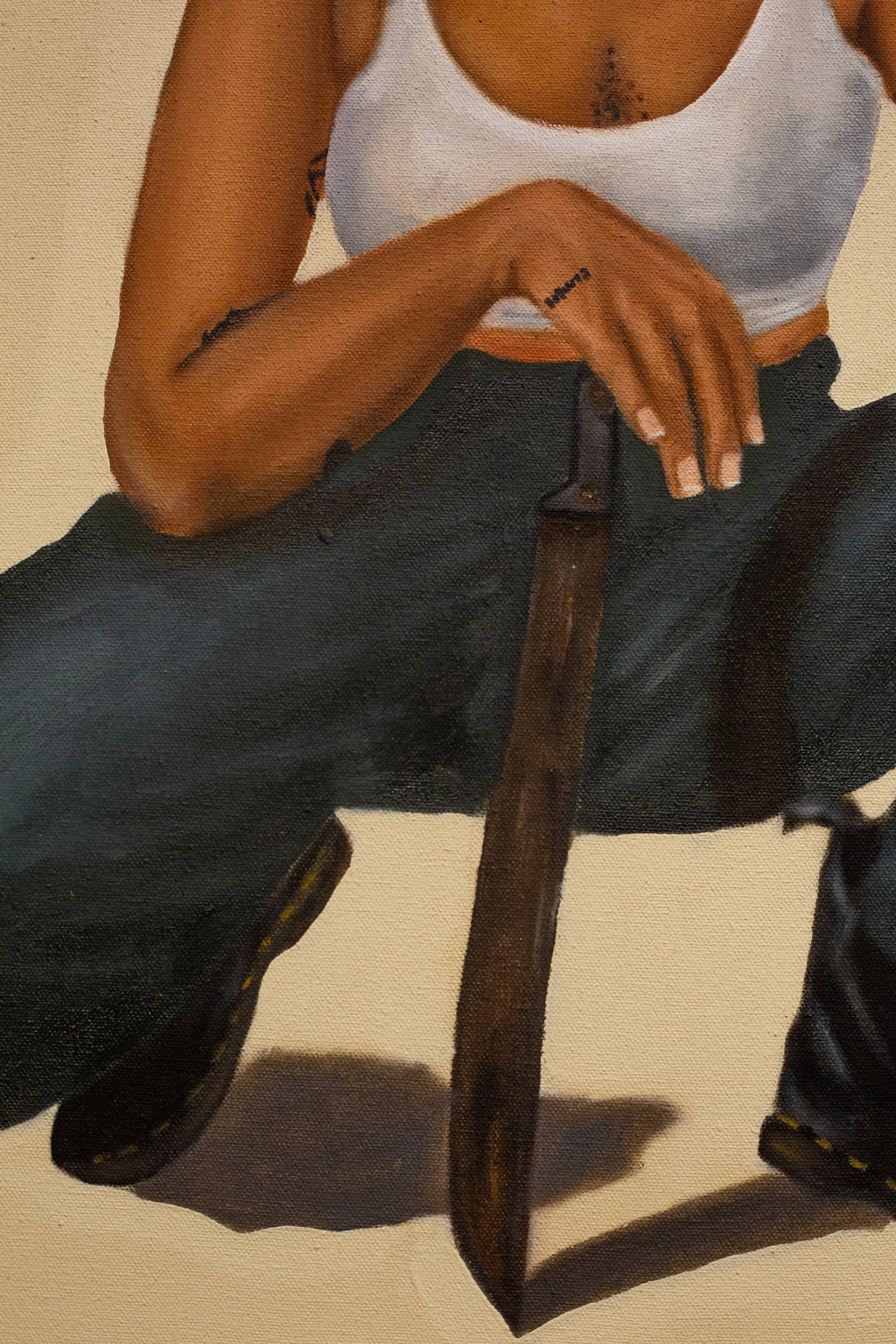

The third pillar of the show is Black Aliveness, whose intellectual underpinnings come from writer Kevin Quashie’s book Black Aliveness, or a Poetics of Being, where he situates the concept of aliveness through the literary work of Black women writers. The works here traverse these three pillars, flowing through, above, and beyond the veil, creating a space, both real and imagined, for Blackness to simply exist.

It’s artist Noah Davis captured sitting in a yard as Henry Taylor’s wingman in loving tribute [Right hand, wing man, best friend, all the above, (2023)]; it’s Amy Sherald’s sartorially styled grisaille portraits that reject the weight of tonality, residing in a space where the sublime is sacrosanct. It’s Jordan Casteel capturing a tender moment between an elderly couple holding hands in Yvonne and James (2017), and it’s Toyin Ojih Odutola’s regal Marchioness (2016) seated wearing a fur coat—she looks at the viewer proudly with a gallery wall of Black art behind her, inviting us to dream, to become, to claim a new reality embodying who Audre Lorde once declared for herself, “I am who the world and I have never seen before.”[5] Much like those days downtown with my father, I felt the nod.

And in that moment, surrounded by Blackness in its beautiful and multifaceted forms, I felt seen.

1. Baldwin, James. Nobody Knows My Name. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2013. Accessed 21 April 2025. Page #117

2. DuBois, W. E. B. Du. “Strivings of the Negro People.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 23 Feb. 2024, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1897/08/strivings-of-the-negro-people/305446/. Accessed 21 April 2025.

3. Blanks, Kevin A. “The Souls of Black Women: Reimagining Futurities Beyond the Veil,.” Beyond the Margins: A Journal of Graduate Literary Scholarship: Vol. 2, Article 2, 2022, https://scholarworks.uno.edu/beyondthemarginsjournal/vol2/iss1/2/?utm_source=scholarworks.uno.edu%2Fbeyondthemarginsjournal%2Fvol2%2Fiss1%2F2&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Accessed 21 April 2025.

4. Quashie, Kevin. Black Aliveness, Or A Poetics of Being. Duke University Press, 2021. Page #154. Accessed 21 April 2025.

5. Lorde, Audre. The Cancer Journals. Penguin Publishing Group, 2020. Page #40. Accessed 21 April 2025. (via Kevin Quashie, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J1Eajj50-Yo&t=18s)