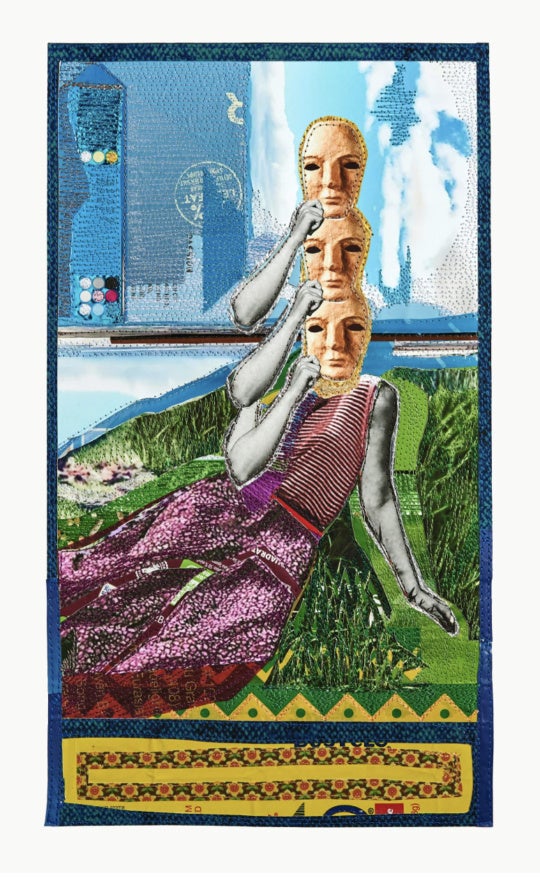

Viewing multimedia artist Lyle Carbajal’s “Romancing Banality,” on view at Tinney Contemporary in Nashville through July 18, is like taking a lesson in semiotics. Everyday shapes and symbols repeat across panels in bright, often primary colors—a blue star here, a yellow cross there. The red, sometimes black, outline of a pistol appears over and over again, as reliable as the rows of SUV-lined driveways in a suburban neighborhood. Many figures don black-and-white Converse sneakers on their tiny, bopping feet (who knew Chuck Taylor would hit the jackpot in adolescent universality? Me, I still have my pair from middle school). These instantly identifiable objects certainly conjure memories and trigger emotions in most visitors, although varied and nuanced in each case. Urban versus suburban; American versus un-American; refined versus unrefined; and traditional versus nontraditional, among others, are all interesting juxtapositions that surface in Carbajal’s work, influenced by his upbringing in Latin America and in a primarily Hispanic home in Los Angeles—“a cultural cornucopia of sorts,” explains the artist, but relatable still to even the most mono-cultured viewer.

Carbajal’s use of shape and color relays a deep connection to traditional folk art, a modern interpretation contributing to today’s ever-evolving definition of visual culture and standards of craftsmanship. “Romancing Banality,” or, more casually interpreted, flirting with unoriginality—perhaps a more fitting title does not exist for Carbajal’s landmark exhibition, as its breadth and depth are quite subtle, a tease even, to use the artist’s own dually amorous and psychological wordplay. Carbajal’s finessed distinctions, however, keep him just on the non-banal side of the line—“the qualities of these images that transcend beauty; or more radically, form another type of beauty that depends on what a thing—whether an artwork or something wholly mundane—makes you feel rather than how it looks,” as described by art writer Adam Eisenstat in his essay “The End of Art and the Heterogeneous Mind: Lyle Carbajal’s ‘Romancing Banality.’”

Carbajal’s compositions are rife with geometric shapes, hard lines, and dark profiles—all characteristics of the Brut style with which he’s so readily identified. His distinct style emerges in the deliberate manipulation and repetition of cultural signifiers, or those objects we see and respond to multiple times a day, yet that fly under the radar of our consciousness; American equivalents include the octagon of a stop sign or the golden arches of McDonald’s. The simplicity of technique and everyday (even crass) subject matter are reminiscent of African-American folk art in the vein of Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial, Minnie Evans, and, a more contemporary comparison, Kara Walker.

The resemblance is really not so uncanny, though, considering the common goal among these artists to represent feeling as much as, or more so than, realistic perfection. As the artist told me in an email: “I never really spent much time looking at Traylor or Dial until people began asking me the question. I think folk artists like the ones you list are about capturing imagery from their daily lives in a simple almost graphic style; I do this.” Carbajal’s Portrait as Narcissist, for example, stands up well to Traylor and Walker’s black-and-white silhouettes. How the few strokes of a single colored pencil create the profile of a man, yet simultaneously produce a simplified picture of the human face we’ve all subconsciously absorbed a million times, not to mention the accompanying memories, is proof that it’s not always about the technical details.

Have I mentioned the margarita bar and the almost life-size “Carniceria y Tocineria” hut? In addition to the representational, two-dimensional works, Carbajal offers a bang-on immersion experience. “Romancing Banality” previously appeared in Seattle (2013) and New Orleans (2014), and prior to each opening the artist spent time in in each city to adequately capture its zeitgeist and incorporate it in some small way into the exhibition. The principal organizer and funder of his own projects, Carbajal explains, “Most of what goes into the installation by way of the cities I inhabit doesn’t normally manifest itself in that city, but rather moves along onto the next.” The order-of-services marquee he documented in Nashville, however, can be seen at Tinney Contemporary now. “Nashville schooled me in a rigid and sincerely ingrained culture with precise cues, mores, and a strong visual language similar in some ways but also very different to other cities I’ve exhibited, like New Orleans, for example,” the artist recalls.

As a first-time viewer of “Romancing Banality,” I can honestly say that, inside the walls of Tinney Contemporary, I felt like I was in Nashville or a comfortable and familiar place, but at the same time not in Nashville—definitely transported in some way. Considering this dual perspective, Carbajal’s comprehensive remarks certainly ring true and perhaps precisely define the uncommon nature of his work despite the common objects and themes: “A term I especially like to pass along and also identify with is ‘reverse eponym.’ This term captures the breadth of what I am trying to do with Romancing Banality.” Rather than a people defining a place, people are defined by the place—natives in every sense of the word.

Elaine Slayton Akin is an arts writer and nonprofit professional in Nashville. She is currently the development coordinator at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. Last year, Akin relocated to Nashville from Little Rock, Arkansas, where she worked as the communications manager at the Thea Foundation and was a board member for Number magazine. Her writing has been published by various journals and magazines, including Number, Arkansas Life, and At Home in Arkansas.