“Where you get all these pictures from, Terence?” the voice wonders as it rises to a sharp, inquiring pitch, filling the bare room with its rhythm. The voice is sweet, with a crisp Southern lilt. It’s a measured voice, the kind that issues forth from a body fortified by the intimacy of family, one that has known love and celebration, joy and friendship, pain and liniments. Its timbre is inflected with the emotional vastness of lived experience.

In its balmy tones, you hear the doting grandmother whose chief preoccupation is the grumblings of others’ stomachs—someone who asks, “Have you eaten?” at first glance, who sternly scolds your mother if she replies no.

This is the voice of Essie Pigatt, the beloved grandmother of Miami-born photographer Terence Price II. Her voice comes to us through Price’s tender seven-minute video Take Your Time (2018), which was on view in his solo show Dancing in the Absence of Pain at Oolite Arts in Miami earlier this year. The video projects dozens of family snapshots and photographs taken from among hundreds collected in family albums, overlaid with a vivid recording of her voice.

One evening, settled in Pigatt’s kitchen, Price showed her each image and recorded her as she recalled the names of those depicted, the places where the photos were shot, and the occasions that marked their making. We are privy only to their voices. We see the pictures; we hear the reactions they elicit, the feelings they induce. All the while Price and Pigatt remain unseen. Yet it’s easy to imagine the smile drawn on the face that the voice belongs to, absorbed with these moments, or Price’s grin as he watches his grandmother’s excitement build.

The video is constructed by a simple conceit: a slideshow of scanned images paired with audio. And yet it brims with a richness that tells something about the complexities of time, family, photography, and memory.

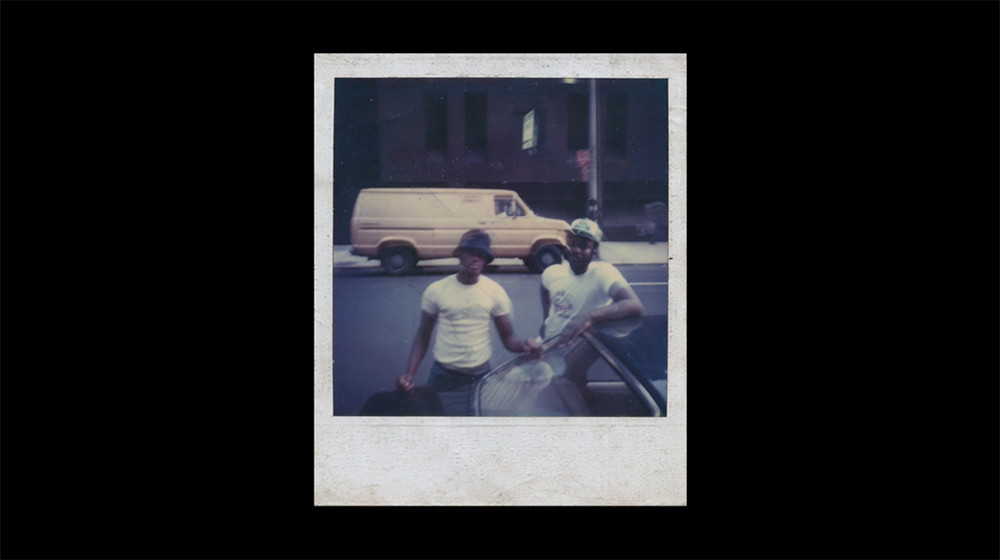

The faces of loved ones, and of her past selves, are returned to Pigatt in the numerous pictures assembled by her grandson. A young Essie poses against an old Volvo, her hand planted firmly on her hip. A man enfolds a woman in his arms, their bodies draped in shadows. A young girl rests her chin upon her folded hands as she smiles into the camera, her hair adorned with two red barrettes. A band of women arrayed before a cerulean pool, their reflections shimmering across the translucent surface. These photographs—Polaroid prints among others—are faded, mottled, foxed, stained, creased, bent, half-torn, overexposed, botched. But the passage of time and the resulting physical and chemical degradation of the prints has neither worn nor dimmed their fierce, incandescent power.

The images work on her mind vigorously as it performs its remembrance. As the pictures flash before her, she retrieves the names and places thought to be long stored away, forgotten even. Here are the memories that lay dormant until gently stirred, plucked from the bed of their bleary somnolence.

As the video passes from image to image, the steady ticking of a clock punctuates the air around the voice. The video lingers longest on a picture of Pigatt with her grandmother-in-law, Viola: two matriarchs, resplendent in purple at dusk, hyacinthine. Pigatt is elated by the sight of it. Her voice breaks, trails off, and then is shot through with belated surprise, as if the scene depicted has suddenly curled through her mind. There is the immediate recognition, followed by a kind of cheerful, splendid disbelief. Hers is a voice animated with the pleasures of the rekindled moment.

Pigatt’s recall is acutely accurate, and she delivers the particulars briskly. “That’s in New York,” and “That’s Bubba cousin,” and “That’s Miss Mitchell,” and “That’s in South Carolina,” she recounts, stamping the pictures with the firmness of her memory.

But there are the inevitable lapses, those hazy pauses when the mind strains to recollect: “I’m lost,” she laments at one instance, unable to recall the gleaming face of the young child who beams in a studio portrait. The voice stammers as her memory falters. At one point, she ventures, “That’s Bubba auntie or cousin or somebody.” The name eludes her, floats in a fog. At another moment, she asks, “Which baby of mine is that?” before finally conceding, “I don’t remember.” Such is the character of a mind as it prods at the fickle contours of memory.

Many of the photographs featured in the video were taken by Price’s late grandfather, Franklin Pigatt, whom Price affectionately calls Bubba. Throughout his life, Pigatt was deeply fond of taking pictures and recording footage of his family and friends—at fish fries, birthdays, during Sunday morning church services, in hair salons. Price has inherited quite a bit of his archival impulse. This spirit permeates Take Your Time and other recent works in which Price has dispensed with the camera and retreated from Miami’s lively streets—where he has made photographs documenting his Carol City neighborhood—to compose works gracefully woven out of the relics cherished and left to him by his elders. (For another video work displayed in an adjacent gallery, Price combed through video footage, recorded it as it played on a TV screen, and then stitched together scenes as he saw fit.) He has pored over hundreds of photos, spent hours watching VHS tape footage, becoming a caretaker of sorts for this richly textured and varied family archive.

Time sways in the video, adrift. The photos provide concrete dates only occasionally: February 1961, April 1963, 1974-1975, 1977-1978. We are otherwise swept along by the flow of images coming from various discrete points of the past and shuttling from one place to the next—New York, South Carolina, Orlando, Miami. This oscillating quality is what gives Take Your Time its richness and complexity, making it a testament to Price’s rigor and devotion as an archivist and artist.

Terence Price II: Dancing in the Absence of Pain was on view at Oolite Arts in Miami, Florida, from January 16 through March 31.