acrylic on wood panel.

“Nobody knows for sure how many thousands in America are warmed by the fire of Hoodoo, because the worship is bound in secrecy.”

—Zora Neale Hurston, Mules and Men (1935)

What Zora Neale Hurston observed about the invisibility of Hoodoo in the wider world of the 1930s still seemed to apply as I tried to write about the phenomenon in Atlanta a half decade ago. Granted, my area of coverage was minuscule in comparison to hers. She visited multiple states and countless individuals to write her great essay on black folk culture, Mules and Men. In reporting a never-published article for the late, lamented False magazine, I unsuccessfully interviewed the proprietor of my now-vanished neighborhood botánica, and I managed to confirm nothing more than the zip code of a purported Atlanta Vodoun temple. Transparent denials (“I don’t know anything about Voodoo,” uttered by the aforementioned purveyor of its ritual components) and dead-end phone calls seem so … 2009 amid the high-profile gleam emanating from Spelman College’s Museum of Fine Art, where Renée Stout’s “Tales of the Conjure Woman” is on view through May 17, 2014. Whether one calls it Voodoo, Vodoun, Hoodoo, or something else, the complex mélange of mysticism, ancestor worship, and practical magic that Stout’s exhibition spectacularly takes on might never again be hidden the way it once was—even recently—in the Americas.

Near the entrance to the gallery, the museum has wall-mounted an exhibition glossary, and the less-than-fixed meanings or spellings of some terms in it suggest a similar lexical clarification is in order here. To be clear, I mainly use Hoodoo to name the system of folk magic implied by the conjure woman in Stout’s title. In hopes of rehabilitating the word Voodoo (if only for myself), I use it to indicate the panoply of solar-centric religions that have African roots and go by names including Vodou, Vodun, Candomblé, and Santeria.

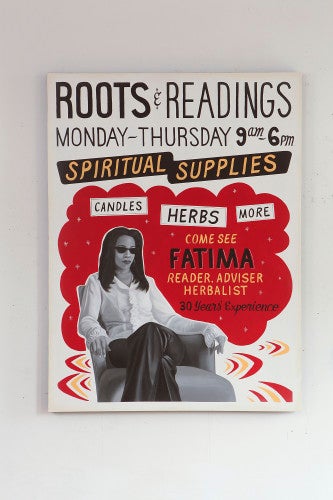

That a glossary is so foregrounded in this exhibition emphasizes the role of text in the narrative and metanarrative aspects of Stout’s creations. The artist is not being fanciful with the use of tales in her title—except in the sense that all fictions are fanciful. As Stout tells it, the titular conjure woman is her (or, more precisely, an) alter ego, a root worker named Fatima Mayfield. Many of Stout’s works here detail projects Fatima undertakes or relationships she has with clients or members of her community. The context in which the artist’s various narratives unfold—the ur-narrative of Voodoo/Hoodoo—is a world about which many Americans remain uninformed or have been, as the Hurston quote implies, misinformed and even misled.

A key weapon in the essential assault of slavery throughout the Americas was the effort to strip enslaved individuals of their own religious beliefs and to impose in their place the beliefs of slaveholders. The irony of Christianity being used to such ends is one exceeded, perhaps, only by the strength some Africans and their descendants drew, amid their own travails, from the story of Christ’s suffering. An additional irony lay in the elements of Catholicism, particularly, that let the enslaved preserve their (perhaps only seemingly polytheistic) beliefs beneath the trappings of compulsory monotheism: Such figures as Legba and Erzulie were syncretized with saints or other venerated figures. In the post-slavery era, belief in such beings and practices came to be seen as backward, even demonic, by many black Christians, who thus participated in the efforts by American power structures to discredit and destroy Voodoo, though to a lesser degree.

No surprise, then, that the more obviously religious aspects of the tradition went underground, which left Hoodoo as a mostly rural practice or showing up secretly in marginal parts of cities. As Stout observes, not even the “black is beautiful” movement of her youth could overcome postcolonial programming that manifested in everything from dictionaries to loaded remarks by U.S. politicians. Stout traces her specific interest in African culture to a childhood museum visit during which she saw a sculpture identified as a “fetish” from “the Congo.”

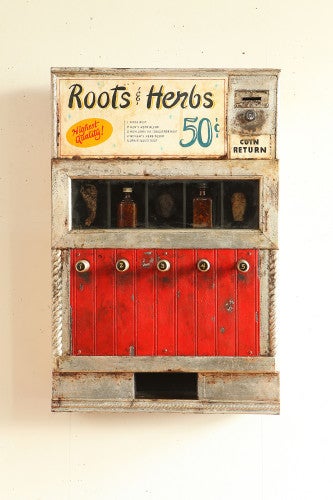

Her early art career as a photorealist painter shows through in some of her more recent trompe l’oeil objects. I initially mistook her 2013 assemblage The Root Dispenser for a reconditioned condom machine, though the work actually consists mostly of wood and paint. Her believably worn surfaces and penchant for retro design cannot conceal the Afrofuturist impulse in her output: a reality wherein a vending machine can deliver a range of putatively magical herbs, from yucca root to orris root. Likewise, The Rootworker’s Worktable (2011) integrates a piece of antique furniture with counterfeit tech that Stout considers a spirit-attuned TV; it would look right at home as set-dressing for some steamfunk production.

How Stout’s work intersects the sacred, even the numinous, separates what she does from any mere generation of surfaces or objects, though. Her embrace/adoption of multiple alter egos in her practice mirrors the Vodou belief that lwas do not merely manifest during rituals but also inhabit one or more of the ritualists. The artist employs ritual-like uses of scent and music in her studio, and both play roles in the exhibition. Watch for the tray of perfumes that visitors are encouraged to open and sniff, and read the back of The House of Chance and Mischief (2008), where Stout lists music she listened to and perfumes she wore (presumably while assembling that work). All of these choices also signal a grasp of neuropsychology—of the way olfactory stimuli intertwine with memory, of contemporary mind models that construe the self not as I but as the jostling collective that makes me.

“Tales of the Conjure Woman” displays an erudition that never seems chilly, a sense of story (and of stories) that almost never feels trite, and a respect for the vast yet delicate task undertaken that seems more playful than pious. Stout transmutes scrap into art I call religiose: not sacred, but about the sacred; not divine but possibly divined; and tethered to mysteries that surround us inside and out.

Ed Hall lives in Atlanta and finds himself at its numerous crossroads all too often.