When a disaster strikes, contemporary society has developed a generic formula of waves of response. Instantly, the media floods their channels with on-site reporters providing factless predictions and “disaster porn” images that quickly generate “compassion fatigue.” Then relief organizations invade, sponsored by global donations and fueled by altruistic ideals. Finally, politicians weigh in, debating appropriate assistance quotas and beginning systematic preparation for the next crop of cataclysms.

However, in the aftermath of this chaos lies the interpretation and representation of these disasters by artists. Whether motivated by factors such as nostalgia, humanitarianism, profit, or relevance, these artists often desire to expand awareness, create discussion, and enact change politically, socially, and culturally. A recent exhibition at the Davidson College art galleries in Davidson, North Carolina, engaged the historic tradition of disaster art in exemplary fashion. Titled “State of Emergency,” it was the first curatorial effort of Lia Newman, the recently appointed director and curator of the Van Every / Smith Galleries at the college.

Typically, the role of a university gallery differs from that of a commercial gallery, and not simply by contrasting artistic theory with capitalistic practice. While the influence of the university often begets didacticism over controversy, an insightful curator can use the idea of a topical introduction or an academic survey to mediate that interdisciplinary challenge. Newman has done both of these. She synthesizes the topic of disasters with an approachable, but critical, collection of contemporary works across the gamut of artistic media that explore the fundamental theme of cause and effect.

Newman begins her curatorial strategy with a theoretical framing by NYU Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication Marita Sturken. She differentiates between three types of disasters: natural, man-made, and hybrids that contain both terrestrial and anthropogenic aspects. Newman complements this categorization in her catalogue essay by clarifying the language of disasters, distinguishing them as abrupt, devastating phenomena as opposed to crises, which play out over a longer period of time. While she could have selected broader watershed moments in recent history, she amassed works addressing “disasters with clear inception points, such as hurricanes, earthquakes, tsunamis, and bombings.”

Newman weaves thematic trends throughout the show without being overly proscriptive of the experience. The ease of identifying the thread of environmentalism pitted against the engine of capitalism does not diminish the impact of works by Eben Goff, Naoya Hatakeyama, Tatana Kellner, Matt Kenyon, and Richard Misrach. Goff threatens Los Angeles with the taste of its own refuse collected in the LA River in his minimalist Flood Cubes (2012). He designed these chromed steel boxes to catch urban detritus in order to show the everyday effect of pollution in our cities. Hatakeyama and Kellner incriminate the construction and energy industries for their environmental crimes and the repercussions for local communities. Hatakeyama’s chromogenic prints, such as Blast 11009 (2004), show the brutality of limestone excavation and the release of toxins into the water and air. Kellner critiques the process of fracking for natural gas in Poisoned Well (2013) by developing a machine that dissolves only the paper of a printed list of the 70 most poisonous chemicals used in the process, leaving the letters to accumulate as reminders of the danger. The misery of the scenes in Misrach’s “Cancer Alley series” (negatives 1998 and reprints 2012), extensive photographic documentation of petrochemical pollution in rural Louisiana, is made worse by the fact that, over a decade since he first photographed this marginalized wasteland, little has been done to improve it. While the works in this category may not win over multinational corporations, they at least provide a broader understanding of these global issues.

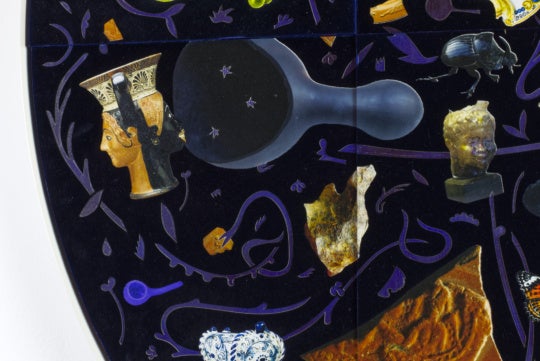

The category that is ostensibly the most visually appealing, the direct aestheticization of disaster may be the most intellectually stagnant. Using rainbows literally and as a color palette, Mario Marzan’s acrylic, graphite, and ink works depict the havoc meteorological disasters have inflicted on his native Puerto Rico. In addition, Kate Kretz’s exquisitely crafted etchings of tornados on antique silver spoons and Joelle Dietrick’s colorful, housing crisis-inspired prints certainly bring cheer to a room of decimation, but pale in comparison to the rest of the works Newman has gathered.

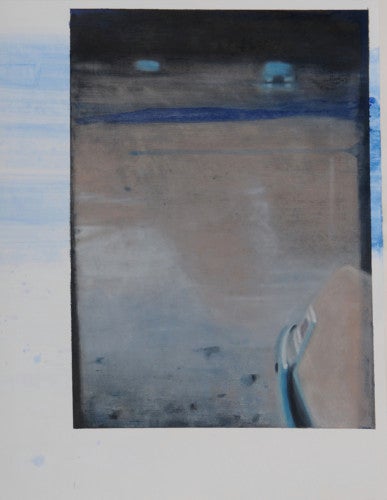

The most successful category in the show compares the active planning and rescue methods with the representations of the passive aftermath. For the video Three (2011), Jason Mitcham recorded the painting on a single canvas of three successive images of a house and created a morphing animation as commentary on the cyclical housing crises. In collaboration with the architectural collective Emergency Response Studio, Paul Villinski has created a mobile dwelling and resource hub for himself and other artists to investigate the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina. Robert Polidori also responds to Katrina in jarring photographs devoid of human presence in his After the Flood series (2005). With her wonderfully eerie critiques of hybrid disasters begun by nature but exacerbated by lamentable city planning, Biloxi-born painter Katherine Taylor blurs the line between abstraction and representation. Finally, Elin o’Hara Slavick and Miki Kato-Starr’s works explore the pain of radiation-cursed Japan from Hiroshima to Fukushima in, respectively, cyanotypes and compilations of paper boats, rice, rope, and light bulbs.

While Newman wanted to avoid the easy figurative dimension of disaster representation in artistic media, the works she selected do not hide from accessibility and cultural relevance. Sturken concludes that this exhibition reveals that “[a]rt about disaster reminds us, poignantly, politically, even angrily, about the precariousness of life.” While the exhibition is primarily concerned with raising awareness of disasters and their representation by artists, it also suggests that we each have a role to play in preventing or lessening their effect.

Curated by Lia Newman, “State of Emergency” was on view January 16-February 28, 2014, at the Van Every / Smith Galleries at Davidson College in North Carolina.

Nick Kahler is an intern architect at Lord Aeck Sargent, an independent artist recently commissioned for Art on the BeltLine, and a writer based in Atlanta.