On September 11, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, hosted a reception for participating artists and special guests for its exhibition “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now.” As has been repeatedly touted, the curatorial team of Don Bacigalupi and Chad Alligood visited 1,000 artists throughout the United States to learn about their work in person. The resulting exhibition includes 102 artists from 44 states, a small but admirable sampling of the two million artists working in the country today.

Contemporary American art is a result of the postwar American Dream—now a tenuous daydream in the wake of the recent financial meltdown, a growing economic divide, and concerns about the environment and global warming. The date 9/11 conjures up complex emotions and horrific images now woven into our cultural unconscious, reminding us that we live in an anxious uncertain world. Artists often reflect this anxious uncertain world in their work.

Several works in the exhibition deal with our relationship to natural resources. Water as a life force is present at the Water Bar, a project by Minneapolis-St. Paul artists Shanai Matteson and Colin Kloecker. It is located in the museum restaurant, where baristas serve free tasting flights of Arkansas H20 to visitors. Guests are asked to describe the earthy, acidic, or sulfuric aftertastes before the sources are revealed. Mineral deposits and agricultural chemical runoff requires the treatment of two of the water sources to make them drinkable, while the water from the naturally filtered aquifer tastes fresh and clean.

Natalie Miebach’s whimsical sculpture O Fortuna Sandy Spins shows water as a force of nature. It begs to be played with as the scale, proportion, and colors used by the Boston artist recall images of Tinker Toys and the Mousetrap game. Made of reed, wood, rope, and bamboo, the “wheel of fortune” chronicles the night Hurricane Sandy hit the Jet Star rollercoaster in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, and the Coney Island Wonder Wheel. With small handwritten notations on the sculpture that reference weather data, she asks us to question our relationship to the weather, the projected sea level rise in our future, and our desire to live at the edge of the sea.

Wind force is referenced in John Douglas Powers (Knoxville) sculptural installation Ialu. The title refers to traditional concepts of Egyptian paradise associated with the reed fields along the Nile River. Tall sticks attached to a mechanical base sway back and forth in front of a video projection of passing clouds. The work is reminiscent of Harry Bertoia’s sound sculpture at the Aon Carter Plaza in Chicago, whose metal rods are activated by actual wind currents, producing an intoxicating sound. The sound made by Powers’s work is a mechanized, distracting squeak that echoes throughout the gallery.

Detroit artist Hamilton Poe’s work Stack makes a direct reference to Minimalism. It features 12 operating box fans installed on the wall in a Judd formation. The air currents cause a straw hat placed on each fan to spin in place, weighted down by plastic eggs inside.

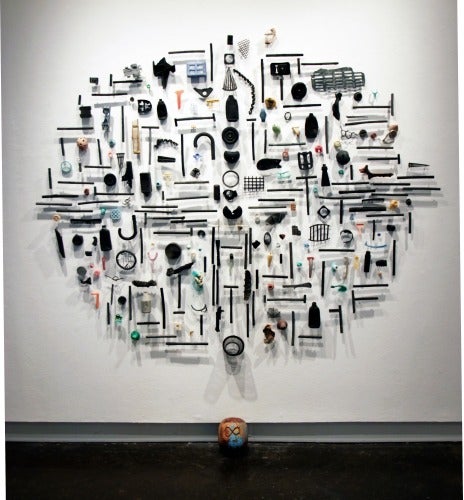

Another nod to 20th-century modernism is Pam Longobardi’s Ghosts of Consumption / Archeology of Culture – For Piet M, an assembled collection of plastic objects she found washed up on beaches. The objects are arranged on the wall to form a large oval shape, which references Mondrian’s Pier and Ocean compositions.. While Mondrian reduced the structure of his pictures down to a series of plus and minus marks, Longobardi does not obscure the individual objects. Collecting litter on beaches around the world brings the artist directly into contact with the intrusion of manmade objects into nature. It would be curious to calculate the collective carbon footprint behind them.

75 by 110 by 5 inches.

Our relationship to animals is addressed in several works. In a large black and white drawing titled Rhinos by Adonna Khare (Santa Monica), a herd of rhinoceros are gathered on rocky terrain. The artist morphs human and animal features together. Their bodies are ruptured and scarred, a direct reference to the fact that the rhino population is hunted for top dollar on the black market, a grim reminder of the relationship between consumption and loss. Another artwork that morphs together human characteristics and animal forms is the interactive installation by Ligia Bouton (Santa Fe) titled Understudy for Animal Farm, a reference to George Orwell’s novel and issues of power, status, and identity. At the special reception I attended, guests were invited to try on the brightly colored fabric pig heads made out of pillowcases. In this case, the images on the two pig heads chosen are Starry Night and Star Wars. The artist photographed participants and posted the resulting masquerades online.

From a nearby gallery, the monotonous marching song of the Mouseketeers can be heard, drawing you into a darkened room housing a sound and video sculptural installation by Danial Nord (San Pedro, CA). As visitors’ eyes adjust, the large sculptural form, with flickering lights from TV sets visible through slits and cracks, slowly reveals itself to be a monumental Mickey Mouse laying on the floor, an exhausted Disney icon.

Just as environmentalists point to climate change and urge us to live in harmony with nature. San Antonio artist Chris Sauter asks us to consider both the cosmos and the microscopic world, to think beyond ourselves. He cut circles of various sizes into a temporary gallery wall that, on one side, creates a starry night sky and, on the other, amoeba shapes. An interactive work by Alberto Aguilar (Chicago) invites visitors to play a game to keep black balloons aloft using hand bells that created a ringing sound reminiscent of meditative practices. Playing is an essential part of scientific discovery, as well as the artistic creativity.

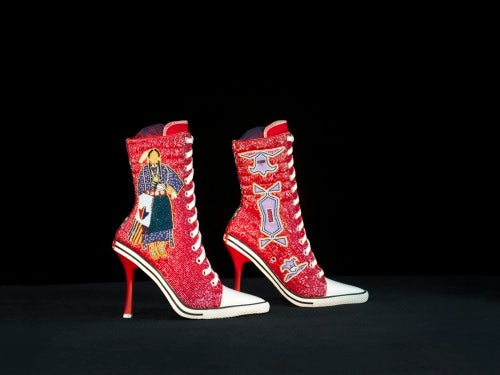

Form follows function, or does it? Using a traditional technique of hand-cut paper, Hiromi Moneyhun (Jacksonville) made a paper moth and Madonnas that are beautiful, ethereal and fragile. Other artists use familiar materials in unconventional ways. Sheila Gallagher (Boston) creates bright painterly compositions by melting and fusing plastic objects together on a BBQ grill. (Don’t try this at home. A video of her working in an alley reveals she is not wearing a mask to guard against the toxic fumes.) Angela Ellsworth (Phoenix) created bonnets with thousands of corsage pins, and Teri Greeves (Santa Fe) covered a pair of high-heeled tennis shoes in Kiowa beadwork. Clods and Grounds by Michigan artist Susan Goethel Campbell (Ferndale) uses postconsumer packaging to cultivate sod into forms that suggest artifacts and talismans.

Location and dislocation in the contemporary world are addressed in works by Chris Larson (Minneapolis) and Jonathan Schipper (Brooklyn). Larson’s 14-minute video Heavy Rotation shows an overhead view of the artist cutting out large circles from sheets of paper that leads to cutting a hole into the floor. A visual vertigo foreshadows things to come as the artist struggles to drop a ladder through the hole into the room below, where the cutting action begins again. Chaos ensues as the objects of a well-appointed studio begin to slide and crash into one another. The room is spinning on an axis, an apt metaphor for the artist in the studio confronting the creative process. Elsewhere in the exhibition, Schipper’s Slow Room presents a living room installation in which numerous objects (furniture, plants, picture frames, mirrors, lamps) are attached to cables that converge in a hole in the back wall. Over the course of the exhibition, a mechanism behind the wall will slowly pull the cabled objects toward the hole. A webcam will chronicle the changes in the room as it becomes disordered.

A number of artists address issues of race and identity. Too easily missed in the installation is photo-documentation of Wilmer Wilson IV’s Washington DC street performance. Titled Henry “Box” Brown: Forever, it was inspired by the 19th-century slave from Richmond, Virginia, who mailed himself to freedom in the North. Wilson (Philadelphia) asked people to cover his body with stamps so he could mail himself to freedom.

Brooklyn artist, Mark Wagner chooses to deal with issues of wealth and the American identity woven into the American Dream in collages made of cut-up US currency, appealing to the anarchist and capitalist alike. Over Grown Empire features the Empire State and Chrysler Buildings towering over George Washington on horseback.

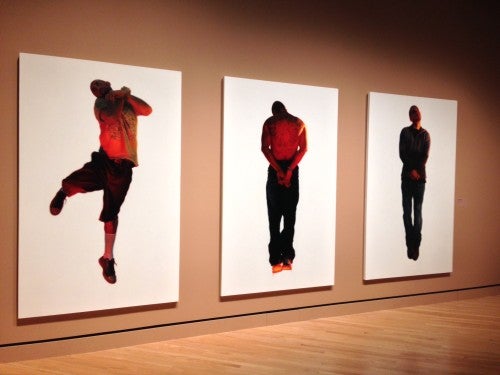

Also hailing from Brooklyn, artist Dan Witz addresses male aggression, rebellion, and intimacy in his large-scale painting Vision of Disorder, Frieze Triptych. Another group of paintings, by Vincent Valdez (San Antonio), deals with suppressed Texas history. The Strangest Fruits depicts three Hispanic male figures suspended in midair against a white negative space, a direct reference to the large number of Mexican Americans lynched in 19th-century Texas.

Atlanta-based artist Fahamu Pecou is known for painting himself on the covers of art magazines, where he masquerades as a rap/hip-hop art star. “Gravity” (2013), a more subdued series of works on paper show the artist with pants sagging in a variety of contorted poses, with street slang hand-written on the page. Pecou engages in word play to express his concerns for how young black males express themselves. For instance, the text in Vantage Point reads: Disadvantage Point / Dis-Advantaged Point. / This Advantage, Point. / This Vantage Point / This. Vantage.

In his multifaceted installation, Terence Hammonds (Cincinnati) encourages visitors to play albums—the Temptations, the Supremes, the Honey Drippers, Ray Charles, Isaac Hayes, Marvin Gay, Tina Turner, Aretha Franklin—and dance on stylized dance floors punctuated with images from the civil rights movement in the U.S. Titled You Got To Get Up To Get Down, the work suggests that cultural exchange and understanding can happen through music.

Critics have been pointing fingers at the museum, saying that the art on view in the survey plays it safe. I don’t believe that is a fair critique. Contemporary artworks do not have to be obscene, obscure, and as difficult to read as a novel by William S. Burroughs to be “good.” If the mission of this curatorial project is to introduce contemporary art to a new and larger audience, it succeeds.

Brad Cushman is a visual artist and gallery director at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.