“History Refused to Die,” an exhibition of works by self-taught Southern artists at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, fills the space abutting the modern masters gallery—Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm is nearly within eyeshot—but it sings a humbler tune. On view through September 23, the show features 29 works by African-American artists, a selection from the 57 pieces gifted to the institution by Atlanta’s Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

Originated by former Met curator Marla Prather and organized by modern and contemporary curator Randall R. Griffey and decorative arts curator Amelia Peck, the exhibition is a visual reminder that history lives on and affects the present day. If you don’t feel the tension in the space, if our Trump-era politics don’t haunt your walkthrough, you’re missing the point. This isn’t just history, it’s about contemporary society today.

The show is stacked with metaphors. From the outstanding quilts of the famous Gee’s Bend region to the powerful assemblages of Thornton Dial and Ronald Lockett, the works exude narrative, despite the fact that most are highly abstract.

An imposing sculpture by Joe Minter introduces visual and conceptual weight at the show’s entrance. Titled Four Hundred Years of Free Labor, the work is a statement that is simultaneously declarative and imperative, a statement sung out by the gritty tools of hard labor of which it is composed. Found materials including metal shovels, pitchforks, and axes are positioned upright to evoke the human form—one pitchfork resembles a hand outstretched toward the viewer in an act of stoic longing. They stand tall, welded together in solidarity. A small, cast iron plate screwed onto the back of an axe features the sole text “Give us this day our daily bread.” Its words describe, perhaps, a poor man’s hope that God may provide what he himself cannot, putting economic inequity on the table for consideration.

Found materials are the tools of the outlier artist, and Thornton Dial makes effective use of them in the exhibition’s titular work History Refused to Die. The monumental piece, which dominates the second gallery, is an abstract assemblage of discarded clothing, tin, drawings, and okra stalks, all pressed against a thin, steel framework. Two doll-like figures chained to the metal framework come into focus as the viewer approaches. A visual tension unfolds slowly as the figures seem to break away from and recede back into the colorful clothing behind them. The greater tension, however, hits immediately upon realization of what they symbolize—the haggard ghosts of an enslaved people, the history that refused to die.

Other hints towards America’s slave trade are more subtle in tone. Dried okra stalks, some pulled from the earth by their roots, form the back of the assemblage. Here, they are no more palatable than sticks, but Southerners know the plant’s importance to culinary tradition in the region. What many white Southerners may not know, however, is that okra is native to West Africa, and that it rode alongside Africans, in the belly of the slave ships, forced to grow new roots in foreign soil. Dial’s piece is a dark reminder that we have not overcome our past, but the artist does offer a small token of hope for the future. Placed over the okra stalks on the backside of the work is a flat, white bird, a dove of peace who, seemingly, has not given up on us.

This hopeful sentiment is echoed in other works, notably Purvis Young’s Locked Up Their Minds. The elements have chipped away at the plywood surface on which the painting is rendered, but that’s no matter. The damaged substrate adds depth to an already rich work of art. In this piece, Young has borrowed the arrangement of some of art history’s most revered religious paintings. Seven haloed figures hold locks in the foreground, two powerful white horses stand tall in the middle, and multiple angels fly gracefully in the sky above. A gray and white border contains the painting like a frame within the moderate sized panel, yet the imagery evokes feelings of freedom as the people surrender their locks to the angels above.

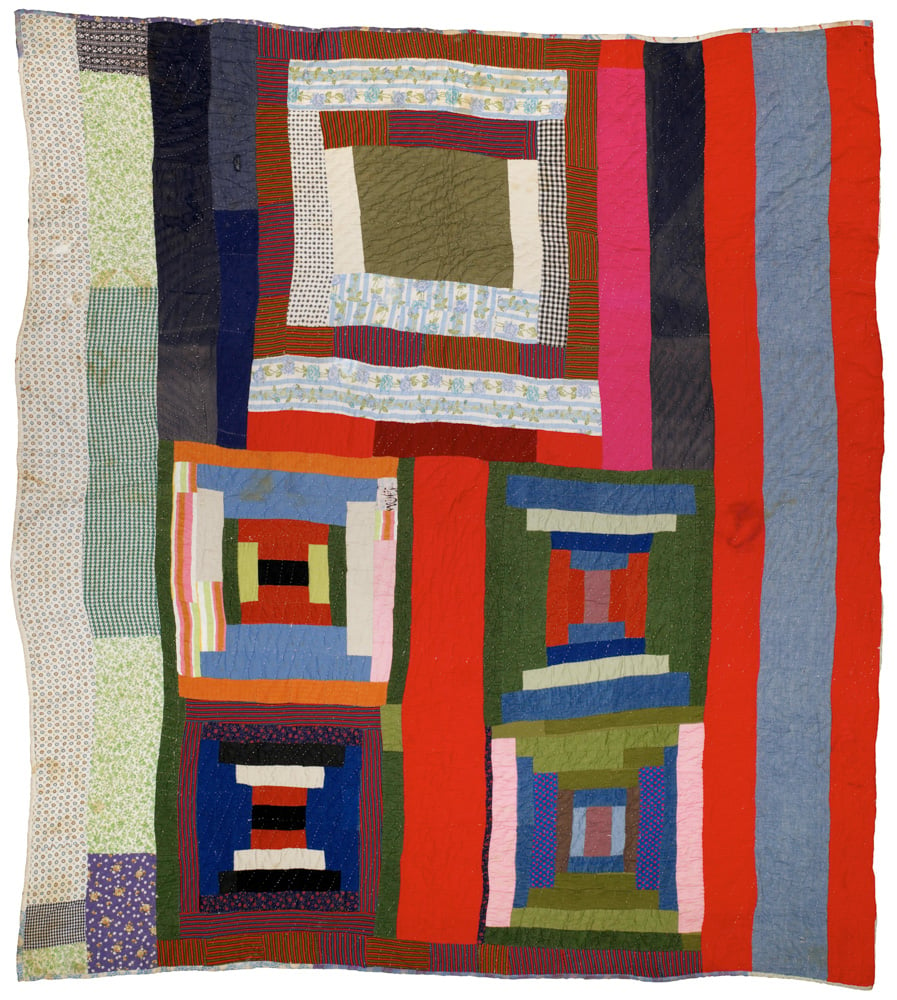

A figurative sculpture by Lonnie Holley, Ruling for the Child, could pass for a relic from an ancient African or Egyptian society. Holley created the piece in 1982 using a waste mold from an industrial foundry. The resin and sand cast depicts a king and queen, side by side, with the female ruler holding a child in her arms. The 10 quilts from Gee’s Bend also conflate the past and the present in the sewing techniques and patterns that have been passed down, mother to daughter, for generations. The past is sewn into the quilts, as much a part of the them as the thread and fabric.

Lucy T. Pettway’s Housetop and Bricklayer with Bars quilt uses representational elements to siphon a story into an abstract composition, pushing metaphor to an extreme. The colorful arrangement, made with Housetop and Bricklayer patterns, evokes an aerial view of the Pettway plantation landscape. Using rectangular blocks, Pettway rendered the geography around her: the large plantation home, four smaller slave cabins, the Alabama River and the agricultural fields (the last element makes clever use of printed calico patterns).

The artists who created these quilts, including Anna Mae Young, Lucy Mingo, and multiple members of the Pettway family, were not trying to create high art to hang on museum walls; they were providing warmth and beauty for their families. Whether as functional objects or as artworks, the quilts are stunning. Some date back to the 1930s, but they seem fresh and relevant today. Their old souls convince me that they know the struggles of 2018 better than I. Moreover, they do something about it.

When William S. Arnett began collecting the work of these self-taught artists from the rural South and then created the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, he built a legacy for artwork that otherwise might be lost, or may not have been recognized as art at all. The artistry within the objects was always there—on the beds in Gee’s Bend, in rural communities across America. Each work is a history lesson, a story of resistance that has built upon itself for generations. Resistance can be quiet, as these artists have shown, but it is never passive. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that, by God, it’s time to mobilize.