Eleven years ago, Sean Miller held an opening reception for the John Erickson Museum of Art’s first exhibition. The reception lasted two minutes, a timespan intended to reflect the diminutive scale of the museum itself, which occupies a space about as large as a shoebox inside a 16-by-12-by-9-inch aluminum case. Along with Miller and artist Jesse Paul Miller (no relation)—whose self-portraiture constituted the debut exhibition—attendees included whoever happened to walk through the lobby of the Seattle Art Museum between 2:40 and 2:42pm on July 25, 2003, where the unauthorized event took place underneath a Sol LeWitt wall drawing.

This week, Miller’s mini-museum will mark its 11th anniversary at the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery at Florida Southwestern State College in Ft. Myers, where a retrospective of the JEMA project, titled ELEVEN and featuring more than 20 mini-exhibitions of work by such artists as Kristin Lucas, Oliver Herring, Yoko Ono, and The Art Guys, runs through July 25. In September, a reconfigured version of the show will go on view at the Harn Museum of Art at the University of Florida in Gainesville, where Miller is a member of the studio art faculty.

The very idea of crafting and curating a tiny, portable museum emerged from the multiple roles Miller found himself occupying in the years leading up to JEMA’s creation: studio artist, art handler at the Seattle Art Museum, and cofounder of the artist-run exhibition space SOIL Gallery in Seattle. As an artist, he made tongue-in-cheek conceptual work that took the museum as its inspiration; for example, amassing a dust ball made of dust collected from 70 exhibition spaces and displaying it along with a dustpan shaped like a gallery. ELEVEN includes this and other pre-JEMA works, along with Miller’s more recent solo creations (he regards JEMA as a collaborative work)—large-scale prints of microscopic photographs of museum dust enlarged to the point of abstraction.

At a moment when SOIL Gallery faced the prospect of relocating to a smaller space, Miller began to toy with a question that seemed practical at first, then absurd. “How small of a space can you run and still have people want to follow it?” Miller recalled while walking through ELEVEN.

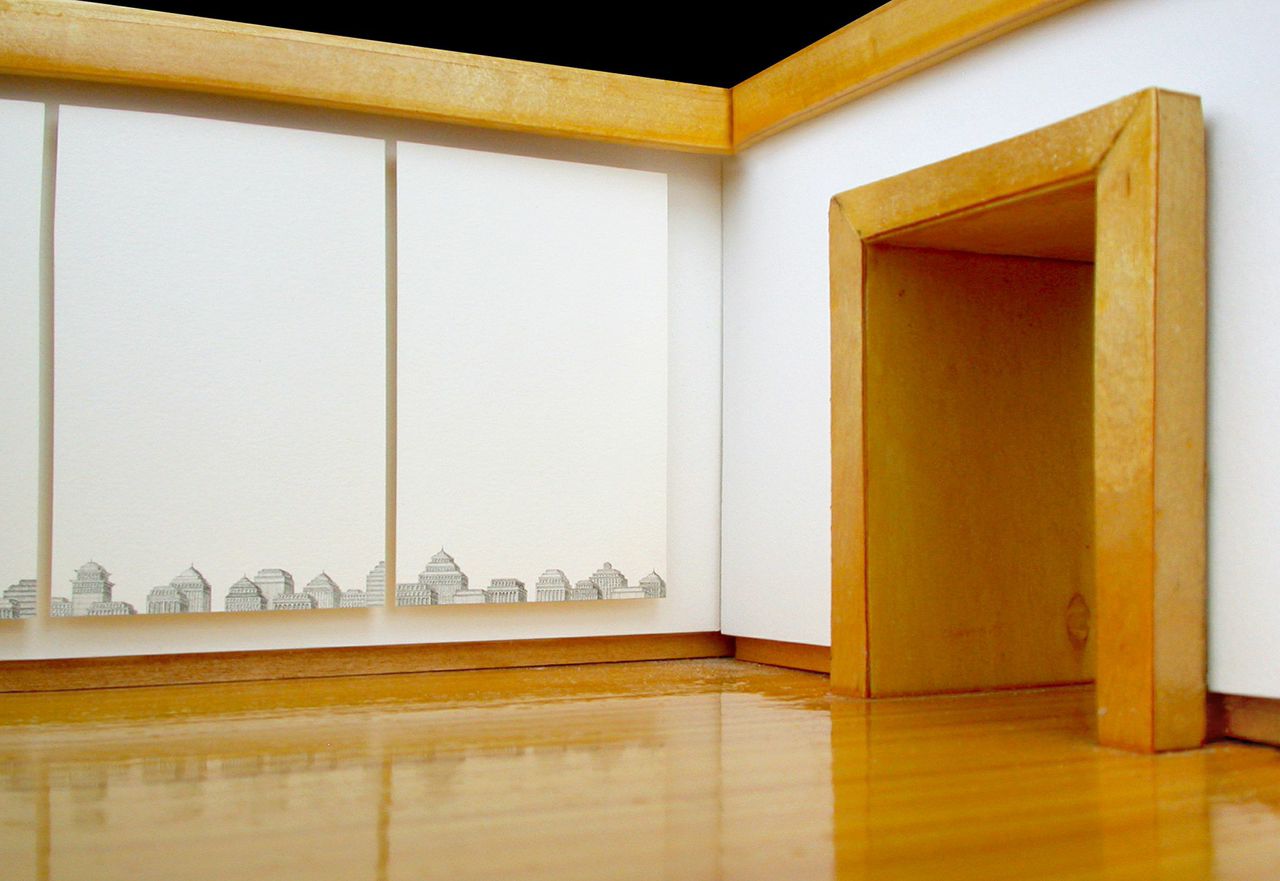

So the John Erickson Museum of Art—named for Miller’s great-grandfather, who owned a jewelry and watchmaking shop in a building that was demolished to make way for the Seattle Art Museum—was born. Like Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise (1935-41), JEMA’s most obvious progenitor, it displays scaled-down artworks in a portable container, but in this case other artists are the focus. JEMA operates like an exhibiting institution, with Miller inviting artists to conceive projects for the space (though these days, with JEMA becoming better known, he also fields exhibition proposals). Typically the contributing artists make their own miniature works, with input and assistance on installation from Miller, who builds the galleries.

With its single, white cube-style gallery, JEMA has played host to solo exhibitions by more than 30 artists since 2003, with Miller functioning as director, curator, preparator, publicist, and occasional courier of the museum to special sites. A surreptitious opening for Sergio Vega’s photographic installation High Art at JEMA—which purported to document South American parrots discussing art making, cultural narcissism and colonialism—took place inside a VIP lounge at Art Basel Miami Beach. When Andrea Robbins and Max Becher lined JEMA’s walls with photographs of Leavenworth, Washington, a town that transformed itself into a Bavarian-themed tourist attraction in the 1960s, Miller marched with the museum strapped to his shoulders, displaying Bavarian By Law is in

Place by Andrea Robbins and Max Becher, and wearing makeshift lederhosen, in the town’s annual Mayfest parade. And with a version of Yoko Ono’s IMAGINE PEACE (2007) inscribed inside, Miller took JEMA to Northern Ireland in 2008, where it became a flashpoint for conversations about peace.

The ELEVEN retrospective offers a charming introduction to the project, which like a long elaborated and much loved toy, comes in a slightly exhausting number of variations and with spin-off accessories (e.g., a JEMA video lounge with its own aluminum case, walking stick “galleries” the size of a softball that can be mounted to the top of a metal staff and taken for a stroll). The exhibition, which was a joint curatorial project between Miller, Bob Rauschenberg Gallery director Jade Dellinger and Harn contemporary art curator Kerry Oliver-Smith, does a fine job of highlighting JEMA’s most significant and engaging achievements. It gives the project its due as a seriously playful undertaking and makes it palatable for a general audience as well as viewers more likely to enjoy all of JEMA’s art-about-art nuances.

For example, at the exhibition opening, Florida Southwestern State College students and other visitors were invited to participate in the only JEMA project to escape the confines of the miniature. New York-based artist Oliver Herring, who is known for involving strangers in his performance-based videos, photographs, and sculptures, stipulated that a JEMA gallery be built that could accommodate a human body. The result is a small-scale stage—a gallery at about ¼ the scale of life-size—which, at the opening, was used as the setting for a spontaneous collaborative performance in which participants covered each other with materials like paint and wheat flour under Herring’s loose direction via Skype. (Since the opening, ELEVEN has displayed the remnants of the performance along with video documentation.)

Another highlight is a JEMA-specific remake of Fluxus cofounder Ben Patterson’s Paper Piece (1960), a performance script that calls for participants to make sound with paper as if it were a musical instrument. The JEMA remake, which was built and performed in 2010, consists of a special miniature gallery made with paper-lined walls and topped with a golden paper shredder—a reference to the golden, or 50th, anniversary of Patterson’s piece. The shredder was used to transform the JEMA gallery walls into sound, and the scraps that fill the denuded space. In ELEVEN, the piece sits silent, already executed, but during the show Patterson, who lives in Berlin, traveled to Ft. Myers, where he performed a different script that entailed covering an inflatable alligator (jokingly substituted for a good-looking woman) with whipped cream, cherries, and nuts, inviting an audience of local residents to taste the results.

The complexity of such projects—the creativity and intrigue of the exhibitions it has hosted and the forms it has taken—keeps JEMA from coming off as a simplistic gag. (A Lilliputian museum, get it?) If the project is, ultimately, an extended art joke, at least it’s a good one.

Megan Voeller is a visual art critic for Creative Loafing in Tampa and an education curator at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum. She co-hosts WEDU Arts Plus, a public television series about the arts.