Indianapolis, Indiana.

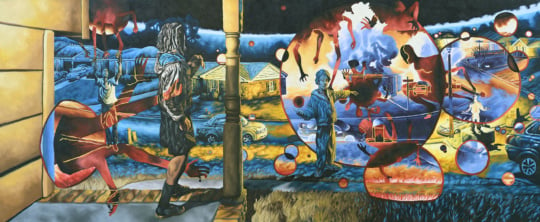

Flat geometric planes of dissonant, wild colors interlock with one another. Graceful, moving lines weave in and out. A jumble of sharp edges and fluid forms intermix to create an unexpected harmony of parts, a sort of jazz composition defining each in Romare Bearden’s 1977 collage series based on Homer’s poem about an epic journey. On view through March 9 at Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum, “Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey” provides a unique opportunity to glimpse the African American modernist’s stunning visual practice and to ruminate on pertinent themes of homecoming and self-discovery.

Rather than illustrating Homer’s story, Bearden interprets the ancient Greek poem about a heroic voyage in a way that both recounts his own personal experience of the Great Migration of African Americans from the repressive South to a place of more opportunity in the North and tells of timeless human struggles we continue to endure today. The tales that Bearden narrates, involving displacement, empathy, justice, peace, and oppression, continue to resonate deeply with a wide, inclusive audience and teach moral lessons.

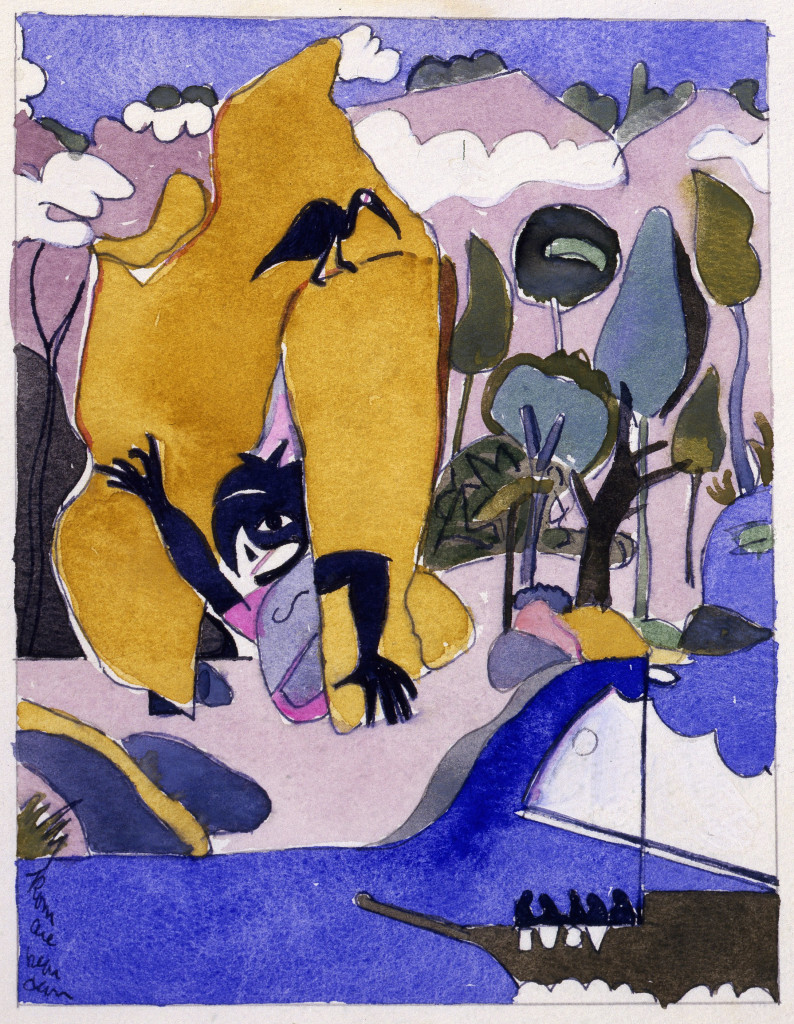

Homer’s vicious Cyclops devours Odysseus’s men with little care, prompting the hero to escape by stabbing the giant in his single eye. In The Cyclops, Bearden renders the monster as much more vulnerable: peering from his cave, arms flailing about, mouth agape, tongue sticking out, Bearden’s representation appears to be playing a game. No one fears this silly creature, as evidenced by the bird perched calmly above him. Rather, one feels compassion for and even identifies with the Cyclops; perhaps Odysseus should have left him alone.

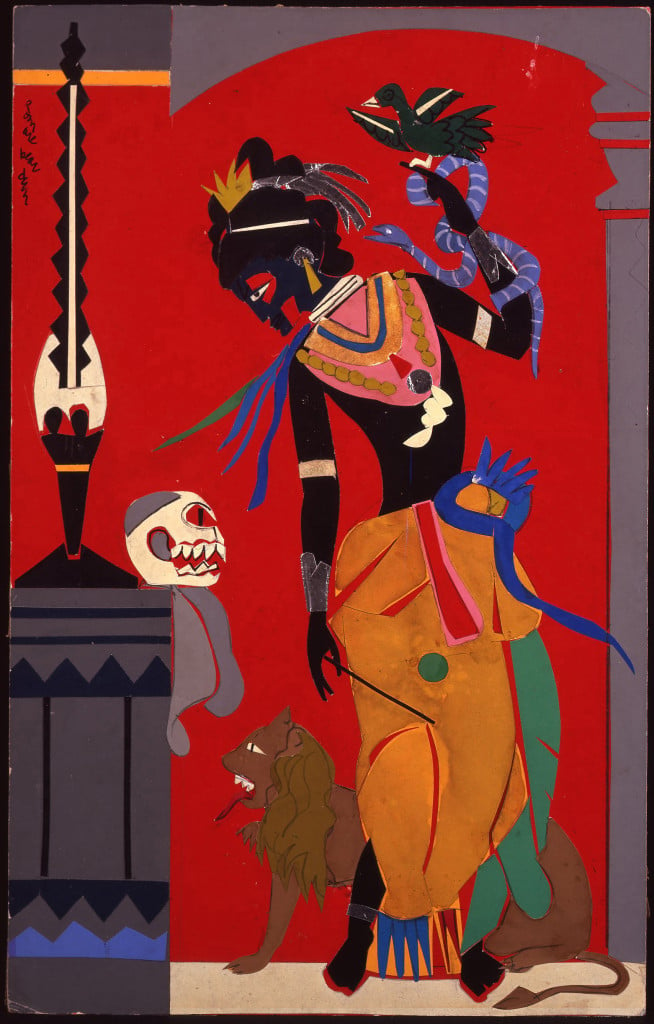

In Poseidon, the Sea God—Enemy of Odysseus, the Cyclops’s father and king of the sea fiercely stirs up the waters and complicates Odysseus’s journey as retribution for the harm done to the god’s son. Inspired by Homer’s association of Poseidon with African heritage, Bearden depicts the furious sea god as a warrior in an African mask. With no indication of Odysseus’s presence in the image, however, Poseidon’s palpable rage, instinct for self-preservation and desire for reprisal are directed instead at real life, at the artist’s own experiences with oppression and cruelty.

To communicate his powerful stories, Bearden employs striking shapes, rich colors, and clear inspirations. Viewing the series brought to mind Henri Matisse’s sinuous line and bold cutouts—significant for Bearden in both form and process—and Athenian black-figure vase painting—particularly suitable for revisiting the ancient myths. Although representing two extremes on the spectrum of art history, these disparate influences both involve a simplicity, an essence of form, and a stark contrast in color that Bearden noticeably adopted. All of these effects are evident in Bearden’s The Sea Nymph, in which Odysseus—dragged underwater by Poseidon’s lashing waves and bound by a cloth—is rescued by the goddess Ino. Her inverted black silhouette set on a vivid blue ground bears a remarkable resemblance to Matisse’s iconic Icarus from his illustrated book Jazz. The Fauve master’s nod to music in the title of his compilation points to the common devotion to improvisation and syncopation he and Bearden share.

Earlier works by Bearden devoted to Homer’s first epic, The Iliad, appear in a side gallery. Watercolors that the artist made after the Odysseus collages are also on view. The small, delightful paintings lack the crispness and vividness of the collages, however, and, viewed after their bolder counterparts, appear somewhat listless.

An ancillary exhibition, Southern Connections: Bearden in Atlanta, presents a selection of materials mined from Emory’s Manuscript Archives and Rare Book Library and other local sources. Photographs of Bearden and his peers (Hale Woodruff, Elizabeth Catlett, Beauford Delaney, W.E.B. DuBois), correspondence, prints, books, and other ephemera offer context and further peeks into the artist’s life. While the supplementary artworks and documentation contribute to a more complete overall exhibition, they also tend to overwhelm and detract from the focus: the 20 spectacular collages, certainly deserving of an exhibition all their own.

Bearden transforms Homer’s Odyssey into vibrant, graphic images that adeptly communicate the familiar epic, reveal his own personal and cultural history, and evoke grand themes that concern the human condition. Both specific and universal, the works in “Romare Bearden: A Black Odyssey” present the artist’s individual struggles and leave space for the viewer to impose her own story and discover her own meaning. They offer quite a journey.

Emily Taub Webb is a professor of art history at the Savannah College of Art and Design, Atlanta.