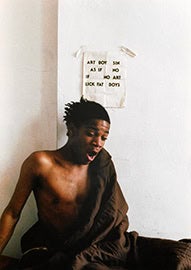

For those of us who came up in the age of Xerox art, band posters, zines and the new wave/punk rock dyad, when the Lower East Side was a blighted hell hole and riot incubator instead of an open-air yogurt shop, the documentary Boom for Real : The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat is not just a portrait of the revered New York artist and wunderkind as a very young man, but of us before the Internet, selfie culture and the greed-stoked ’80s, an era through which Basquiat is more commonly viewed. Though it’s ostensibly a biopic, Boom is also a portrait of the formative creative fester of youth in general, a Slacker or American Graffiti of the New York art scene.

Boom for Real features a mother lode of bold-face writers, filmmakers, and artists: filmmaker Jim Jarmusch, writer and historian Luc Sante, music pioneer Fab 5 Freddy, artist Kenny Scharf, writers Glenn O’Brien and Carlo McCormick and other movers and shakers of New York City’s underground scene in the ’70s. In interviews, they recount watching a teenage Basquiat emerge on the scene, tentative and charming, crashing on floors and couches for the night, decorating city walls and every surface of his apartment with his childlike drawings and wordplay under his artistic persona Samo, for “same old shit.”

Boom for Real is about burgeoning creativity. What emerges is a picture of Basquiat as a product of the burned-out hovel and economic collapse of New York City’s Lower East Side, which also happened to play host to a remarkable creative nexus. The young artist had an art band called Gray, and developed a hand-painted line of clothes under the label Man Made and convinced Patricia Field to carry them in her trendy boutique. The film documents his incubation alongside the creative influence of filmmakers, artists, graffiti writers, curators and novelists. The way Jarmusch and others speak of Basquiat’s meteoric rise is with the beaming and astonished pride of a parent.

As in Eastern Europe and Russia under the Soviets, disadvantages became advantages. The Lower East Side squalor, which filmmaker Sara Driver presents in archival footage, made it a cheap, creative laboratory for artists and writers of the time. Uptown, graffiti artists like Lee Quinones and Al Diaz (who helped develop the Samo tag with Basquiat) and the nascent hip-hop scene took similar advantage of blight, tagging entire subway cars and abandoned buildings with their work. Eventually, the two worlds: the uptown, largely black hip-hop and graffiti crowd and the downtown white New Wave and punk rock worlds collided, creating the potent brew of influences that Basquiat was steeped in.

The kids of the Lower East Side stood in opposition to the Leo Castellis and Ileana Sonnabends, whose galleries, as Luc Sante cracks, felt like walking into banks. While politically minded artists at those galleries mulled over international conflict and revolutions, scruffy denizens of the Mudd Club and Club 57 were dealing with murder and heroin in their streets and sometimes on their stoops. (Cheap heroin slew Basquiat at age 27.) It was the era-defining exhibition “The Times Square Show,” organized by the artists’ group Collaborative Projects, commonly known as Colab, that put Basquiat under the larger art world’s nose and piqued the interest of Metropolitan Museum curator and collector Henry Geldzahler, who purchased a Basquiat from the show.

Basquiat glides through Boom for Real, sprite that he was, like a visitation. Never interviewed or his voice heard, the artist is seen in documentary footage tagging walls or smoking and communing in claustrophobic New York apartments. He becomes, in some ways, Driver’s evocation of the creative spirit in human form, a touchstone for all of the other creatives interviewed. Though he shared something in common with the similarly street-centric graf writers of the time, Sante attests to how Basquiat was in a class of his own with his lyrical and literary focus on language and his koan-like tags inspired by another downtown transgressive, William S. Burroughs.

Told from the different vantage of a female filmmaker (and Jarmusch’s main squeeze), Boom for Real is less a biopic as a case study in how creativity is born and nurtured, and how tentative experiments can one day bloom into coherent, complex work. It is a potent love letter to Basquiat but also a Proustian remembrance of a time past, when Driver and others found like-minded souls in a pre-gentrification New York City, and anything seemed possible. A partial debunking of the popular mythos of the singular artistic genius, Driver’s film shows that, instead, it takes a village.

“Boom for Real: The Late Teenage Years of Jean-Michel Basquiat” can be seen at Landmark Midtown Art Cinema through May 24.

Felicia Feaster is a managing editor at HGTV and Travel Channel, the co-author of Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Film, and writes frequently about art and culture for a number of Atlanta and national publications. She is also a BURNAWAY board member.