This summer, the Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA) hosted the “first-ever exhibition that highlights the work of women as game designers and artists.” XYZ: Alternative Voices in Game Design, took on a political curatorial project, working against a popular understanding of game design as a “boy’s club” and of video games as a bastion of masculinity and violence [July 14-September 2, 2013]. XYZ provided a highly interactive experience where visitors were told a story of “alternative gaming” brought to them by women.

A gaming newbie, I appreciated the efforts of the exhibit’s curators to painstakingly strip placards of jargon and insider knowledge; they took their pedagogical role seriously with regards to the museum’s more novice visitors, addressing “non-gamers” directly in their captioning. Gallery attendants encouraged visitors to play any of 18 different games—each one selected as an example of an “alternative” voice in the world of game design, and each of which was created, in some capacity, by a woman.

MODA’s galleries converted well into space of playful introduction, interaction and discovery, divided into four zones—Arcade, Hallway, Den, and Gallery—each of which told a distinct part of the exhibit’s alternative gaming story. The museum lobby housed the Arcade where visitors could play three games, including Kaho Abe’s Ninja Shadow Warrior—a video interface game where players move their bodies around the lobby in order to “hide” behind objects that appear on the screen. Players are encouraged to participate, and their bodies become something of an acrobatic spectacle for passers-by.

After the Arcade, visitors entered the Hallway—a chronological timeline evidencing women’s “early” influence on video game production. Opposite the timeline, visitors, if they took the time to stop and watch, found the “Out of the Box Video Wall” with three screens featuring videos of games that could otherwise not be brought to MODA because of their “unique display challenges.” Many of these games took place, at least partially, in the “real world,” casting virtual play onto urban zones and lived experience. One such game includes Margarete Jahrman and Max Moswitzer’s Pong Dress, an art performance wherein Jahrman stands in a video-arcade wearing a little black dress studded with led-lights upon which two participants can play video-pong with vintage Nintendo controllers. The game, in real life, incites sexual tension via the interplay between body, game, player, and play-scape.

From the Hallway, visitors entered the Den, an “informal family living room” of Ikea-esque furnishings, featuring commercially successful and “family-oriented” (read: non-violent) games. Visitors were encouraged to sit and play each of the games, time permitting. In the Den, visitors animate the games for others who stand behind watching and listening. The otherwise private den of the family home is cited, in this context, as a display, a platform, and a possible setting for this story of alternative voices in gaming culture.

However, it is on the threshold between this homey space of gaming frenzy and the final room in the exhibit—called the Gallery—where I question the curatorial hand(s) behind XYZ. Entering the Gallery, I overheard an attendant describe the games on view within as, “more about their message than the experience,” and he noted that they were not designed to be “fun.” Although the exhibit’s curators likely did not script this rather unfavorable gloss, upon entering the room, it became abundantly clear why one might read its role as such.

The Gallery, which was by far my favorite part of XYZ, quite clearly represented the margin’s margin—those games understood to be so alternative that their logical place in the constructed geography of XYZ: Alternative Voices in Game Design could only be clustered together in the back, on their own special Isle of Misfits.

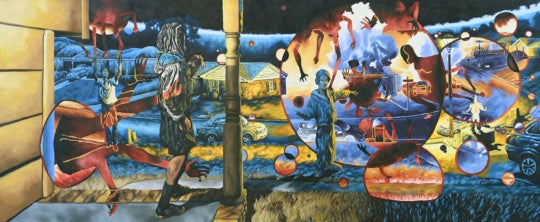

Among the eight games featured in this collection were two games about transwomen’s experiences, including Anna Anthropy’s Dys4ia (2012), a retro-style computer game designed to demonstrate the emotionally-studded path of gender transition. The gallery also contained two analog games, including Brenda Brathwaite’s Train (2009), a game where players compete to transport boxcars of yellow pawns to various surprise terminals (spoiler alert: the terminals turn out to be concentration camps). Two other digital games in the Gallery were created not by singular artists, but by groups of designers, including The Path (2009), a horror-themed, multi-linear riff on the Little Red Riding Hood story that contrasts age-based experiences of feminine life; and, finally, The Night Journey (2010), a zen-Buddhism inspired game with no goal and no end, in which players are visually rewarded for moving as little as possible. The games in this room were clearly designed to open the possibilities of what a “game” can accomplish or express. However, grouped together as they were, the common trait among these games could only be read as “other.” Placed in stark contrast to the colorful, cuddly play-Den next door, the Gallery seemed to be the place where “fun” goes to die. Exeunt, end of gaming exhibit.

Overall, XYZ presents a fascinating and accessible response to over-determined stereotypes of World of Warcraft and Grand Theft Auto, but I find it important to draw attention to a disappointing undercurrent that pervades its curatorial and installation decisions: Rather than undermine the stereotypes it targeted, at best XYZ remained ambivalent to them, and, at worst, fed right into their reproduction.

Let me explain: in it’s effort to rescue women from the as-yet-untold history of gaming, XYZ presents these women designers as the leading protagonists of non-violent and contemplative resistance in a battle against a rough-n-tough good-old-boy’s club of capitalist, war-mongering consumption. See the irony here? In describing many of the women-engineered games as “family-oriented,” the curatorial voice aligned women’s game design with hearth-and-home values, implying an all-too-natural analogy between the body of the woman designer and its presumed cultural role as mother. Similarly, in presenting the “girl games” movement of the 1990’s, the exhibit seemingly applauded research methods by which (mostly women) designers could engineer games specifically for girls. Here, I do not refute that a survey of “women” and “girls” might reveal a set of statistically-derived characteristics which may be effective in selling games to these consumer groups. Rather, I want to suggest that uncritically presenting this picture of sex/gender in the context of an exhibit that claims to combat a marginalizing view of women only perpetuates that view. It asserts that women are valuable and have always been because, after all, they are women, and we all know what that means.

Do we, really? Why does an exhibit that bothers to include games by transwomen—a move I applaud wholeheartedly—eschew the opportunity to ask what it means to be a woman, anyway? In contrast to the lengths taken by its curatorial team to push against a narrow concept of “game,” the exhibit rather lazily relies on the concept of “woman” as a central criterion for the selection of its pieces. This is not to say that XYZ isn’t a valuable intervention in a developing popular conversation about gaming—it was well worth the six hours I spent navigating it. Rather, I wonder why the curatorial team seemingly did not hold themselves as accountable in the contributions they made to a concomitant conversation about sex/gender—one that they invoke as a key motivation in initially crafting the exhibition.

–Sarah Stein is a JD/PhD graduate fellow in the Department of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies at Emory University. To finance her affluent lifestyle, she sells t-shirts on cafepress.com that read, “tanta escuela me apendeja.”

House rules for commenting:

1. Please use a full first name. We do not support hiding behind anonymity.

2. All comments on BURNAWAY are moderated. Please be patient—we’ll do our best to keep up, but sometimes it may take us a bit to get to all of them.

3. BURNAWAY reserves the right to refuse or reject comments.

4. We support critically engaged arguments (both positive and negative), but please don’t be a jerk, ok? Comments should never be personally offensive in nature.