14 x18 x 2 inches, 2013, courtesy the artist and Whitespace Gallery.

Ann-Marie Manker’s latest exhibition, Under the Rainbow, on view at Whitespace Gallery, plays fast and loose with feminist ideas and cultural stereotypes, inevitably doing a disservice to both [April 5-May 11, 2013]. The cartoon-ish paintings and lace sculptures in this exhibition muddle a stock vocabulary of symbols relating to feminism and Islam—with a vague idea of oppression—and cross-reference news reports from the Middle East with American voyeurism, all in an imagined landscape of rainbows featuring cloud-men. In short, Manker creates a confusing confluence of themes that lacks serious investigation and promotes the very stereotypes she seeks to disarm.

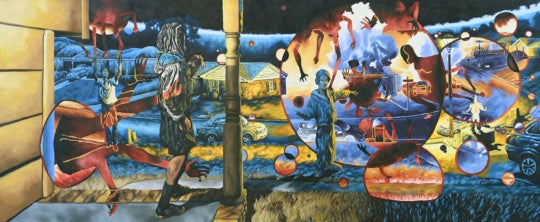

An attractive young white woman stars in the paintings in Under the Rainbow. Though the young woman is pretty, she appears as an archetype more than an individual. Like a comic-book heroine, she stands static in cartoon settings where rainbows and clouds abound, and darkness undergirds it all. Her face is always presented as obscured, be it by her own hair, rainbow colors which bleed over her cheeks and mouth, or a Muslim veil.

In Praying Mantis (2013), this woman is depicted heroically floating in a sea of black clouds, her eyes closed as if in ecstasy, sporting a firearm in each hand and wearing vampy black heels, the frilly black skirt of a French maid costume, and a white khimar. The overt sexiness of her attire and orgasmic pleasure in her expression collide with the religious veil and wielding of weaponry. The same outfit appears in Ave Marie (2013) wherein the orgasmic expression has been replaced with a fierce gnashing of gold teeth. The khimar is now rendered in pastels. The figure’s arms are crossed across her chest defensively; her fingers grip the guns tightly, ready to unleash fire.

These images are disturbing, not because they are provocative—they read flatly—but because they come across as incredibly thoughtless. In interviews Manker describes her interest in female suicide bombers and her imagining of the fantasies that motivate them, which develops into the fluffy rainbow-strewn fantasy-land depicted in her works. However young a female terrorist may be (occasionally as young as 14 but according to a Huffington Post article the average age is early 20s) it seems demeaning to project their idea of heaven as that of a My Little Pony-scape and insensitive to actual Islamic ideas of the afterlife. To focus on the cliché feminine desires—rainbows and sexual freedom, as evinced by the racy outfit under the khimar—is also in ignorance of the real motivations of female suicide bombers which, as it turns out, are identical to that of men.

In a 2008 New York Times Op-Ed, doctoral student Lindsey O’Rourke dispels several myths about female suicide bombers including the idea that their motivations may be gender-specific, and related to sexual inequality or religious-mandated insubordination. O’Rourke’s research reveals the motivations of male and female suicide bombers to be quite similar and shows the fallacy of popular misconceptions about suicide terrorism in general. According to O’Rourke, there is no one demographic profile for female attackers and, what’s more, Islamic fundamentalism isn’t to blame. O’Rourke found more than 85 percent of female suicide terrorists since 1981 were urged on by secular organizations and many came from Christian and Hindu families.

Of course, the real issue concerning the works in Under the Rainbow is not whether or not Manker knows these facts, but her over-simplification of imagery. Manker transformed her model into a female suicide terrorist by giving her a specifically Muslim article of clothing, thereby playing upon prevailing fears and reflecting media-propagated stereotypes concerning Muslims. Her use of a white, barely-clothed American model to exemplify this Muslim terrorist is also egregious, as it appears to ridicule the values of Islam and quite literally white-wash the appearance of Middle Eastern women.

After the events of last week in Boston and the aftermath of fast-flying accusations and the media whirlwind takedown of possible suspects

(all young men with dark skin), the presence of the khimar in Under the Rainbow reads all the more clearly as a stereotyping of Islam and a vilification of the religious veil. This read isn’t at all exclusive to this week; the majority of opinions and fears surrounding the Boston bombing are informed by the events following the World Trade Center attacks and Manker’s work explicitly exists in a post-9/11 America. Many women wear hijab and other head-coverings by choice and though the veil has also been criticized as oppressive, that conversation isn’t considered in these works.

What is at stake is the mischaracterization of the religious veil, or any other visual symbol item or characteristic connected to Islam, as connected to terrorism. Manker’s depictions of female terrorism buy into the fears surrounding Islam and regurgitate them onto the panels on which she paints.