In Metamorphoses, the Roman poet Ovid described a world emptied of permanent natures, a constant flux in which anything could potentially turn into anything else. Not surprisingly, Vik Muniz has adopted the poet as his patron saint, and their shared attraction to mutability shines through in this retrospective of the Brazilian-born artist’s work. The exhibition, which was organized by the High Museum of Art and the Minneapolis-based Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography, is having its debut in Atlanta before embarking on a national and international tour. Muniz’s abiding interest is in the collision between image and matter. His large-scale photographs are often replicas of other artworks, among them pictures of celebrities, paintings by Monet, Richter, and Caravaggio, film stills, and sculptures by Richard Serra and Tony Smith. He recreates these original works in an array of oddball materials, including garbage, wire, soil, dust, thread, clouds, caviar, diamonds, peanut butter, chocolate, black beans, spaghetti, toys, sugar, magazine clippings, heaps of pigment, mounds of earth, liver and stem cells, and individual grains of sand.

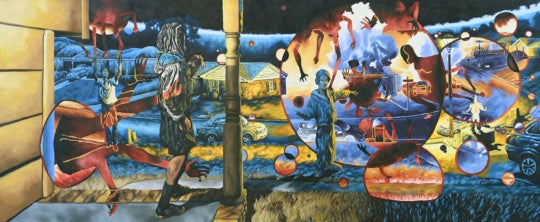

There’s no denying that many of his large-scale works can elicit wonder at first glance. In part, this comes from the sheer size of the photographs and the sculptural installations they’re derived from—his garbage-based pieces cover much of the floor of Muniz’s warehouse studio, as seen in the 2012 film Waste Land, about his project working with trash pickers at the world’s largest garbage dump in Brazil. It’s surprising and a little unsettling to see Lewis Carroll’s young inspiration Alice Liddell depicted in a colorful splash of hundreds of toys, or Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son realized in discarded piano keyboards, fire extinguishers, stop lights, tires, and oil drums. Such crowd-pleasing pictures are among Muniz’s most celebrated, and they show him at his peak as a master of spectacle. Their scale gives them a carnivalesque razzle-dazzle, the clamor of details drags the eye back and forth between macro and micro, and the easy familiarity of their sources lends a knowing wink to the audience. They rely on antic artifice bordering on outlandishness—in Susan Sontag’s terms, “the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not.” In the most exact sense of the word, they’re camp. What, after all, could be campier than depicting Marilyn Monroe or Monica Vitti in a pattern of glittering diamonds laid on an inky background, or making photographs of cartoon clouds doodled in skywriting? These are cute gags that neither ask for nor compel much reflection. The same camp sensibility animates his renderings of pulp horror icons Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi in caviar. While the shimmering black pools radiate a wonderful, glossy menace, their luxurious connotations are at odds with the actual lives of the stars, which were marred by illness, poverty, and drug addiction.

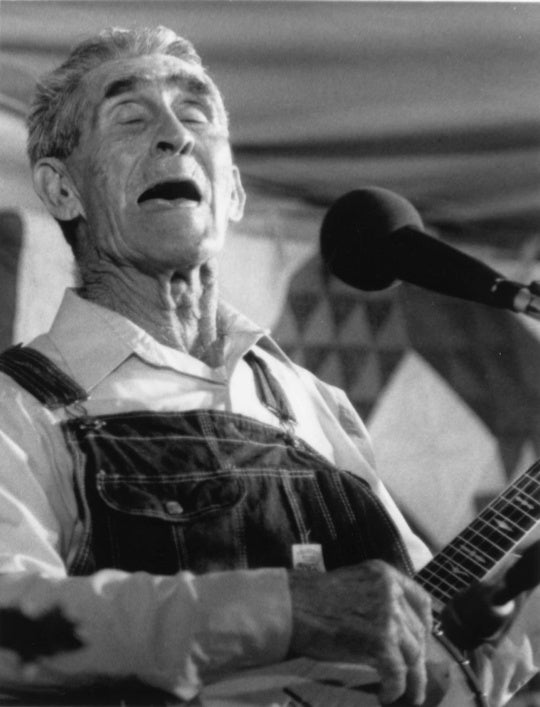

With respect to his artistic sources, Muniz has claimed that “[m]y copies ask the viewer to look harder at the original.” This sounds modest and deferential, even didactic. But it also highlights how pale these copies can seem. Compare Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère with Muniz’s variation made from magazine scraps. The distinctive pleasures of close looking, of attending to the fine details of a work’s composition, lighting, and brushwork, are replaced by an aimless ramble through a field of visual clutter. Precisely because its details are arbitrary and meaningless, Muniz’s flattened version can’t sustain this level of attention, and it’s unclear how to use it as any sort of guide to comprehending Manet’s achievement. (Though I’d allow for some exceptions; his re-envisioning of Monet’s Rouen Cathedral in heaps of bright pigment, like a granular landscape of colored flakes, is genuinely transformative.) It’s frustrating that Muniz’s showy images can feel so thin, since when he isn’t making mimetic puzzles he’s capable of great delicacy and intimacy. One of his earliest series, Sugar Children, shows his exceptional hand at work in portraits of the smiling kids whose parents labored on the cane plantations of St. Kitts. The surfaces of these portraits are lovingly textured and ridged with fingerprints. His Pictures of Garbage are similarly attuned to the particularities of the faces and character of the garbage-pickers of Rio, whose likenesses he reproduces in trash while still imbuing them with dignity. Muniz’s social concerns and philanthropic ambitions are well-known and the empathy and passion that lies behind them are evident here. Some of the less frequently seen works on view shed light on the origins of Muniz’s mania for appropriation and also clarify his relationship to photography. It’s tempting to think of the camera as just the means to documenting Muniz’s sculptures. But in Best of Life, of 1989-90, he created drawings from memory of famous pictures from a Life Magazine photo anthology, then blurred them slightly and printed them in halftone to mirror their original printed appearance. These “memory renderings” look watery, as if half-seen through tears, and they speak to our shaky hold on even the most widely circulated of images. Muniz’s latest work has him casting about for ever more exotic materials to work in. The Colonies series, a collaboration with MIT biologist Tal Donino, is a set of microscopic images made through artificially guided cell growth. Liver (Hepatocytes) Cell Pattern 1 (2014), for instance, has the decorative patterned look of a purple and gold rug. This is tame by bio-art standards, and it doesn’t do much to transform our understanding either of the artistic or the cellular processes involved. Sandcastles takes its name literally, using focused ion beam microscopes adapted from the semiconductor industry to draw outlined castles on single grains of sand. While technologically impressive, they feel rudderless and slightly lost.

The breadth of the exhibition is commendable, and in surveying the variety it contains, I’ve formulated a tentative generalization about Muniz’s work: his most successful images are the ones that most closely approach human scale. His portraits are a case in point, but I also admire the sinuous, heaped coils of his thread drawings, and the marvelous solidity of his minimalist sculptures rendered in tiny, fragile patterns of dust sweepings. His more monumental work, for all its wit, feels like the Cheshire cat: an empty grin without a face. Muniz is at his most tough and engaging when he’s metaphorically sweeping away the ashes of his predecessors, rather than replicating them with his bottomless bag of tricks. “Vik Muniz” is on view at the High Museum of Art through August 21.