Within the gallery walls at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, multidisciplinary artist Sherrill Roland speaks in code. Processing Systems: Numbers by Sherrill Roland is concentrated around seven large aluminum structures resembling oversized Sudoku puzzles with digits etched into the 81 square cells on the metal surface. Traditionally, each row, column, and section within the 81-cell grid must be filled with one of 9 single digits; however, in Roland’s version of the game, 5 or 7 numbers repeat themselves, corresponding to specific ID numbers issued to federal and state inmates when they are admitted into prison. These monikers become their primary form of identification on the inside, and Roland uses them to create numeric portraits embedded within a game of logic that the viewer must reverse engineer to glean insights into his subjects.

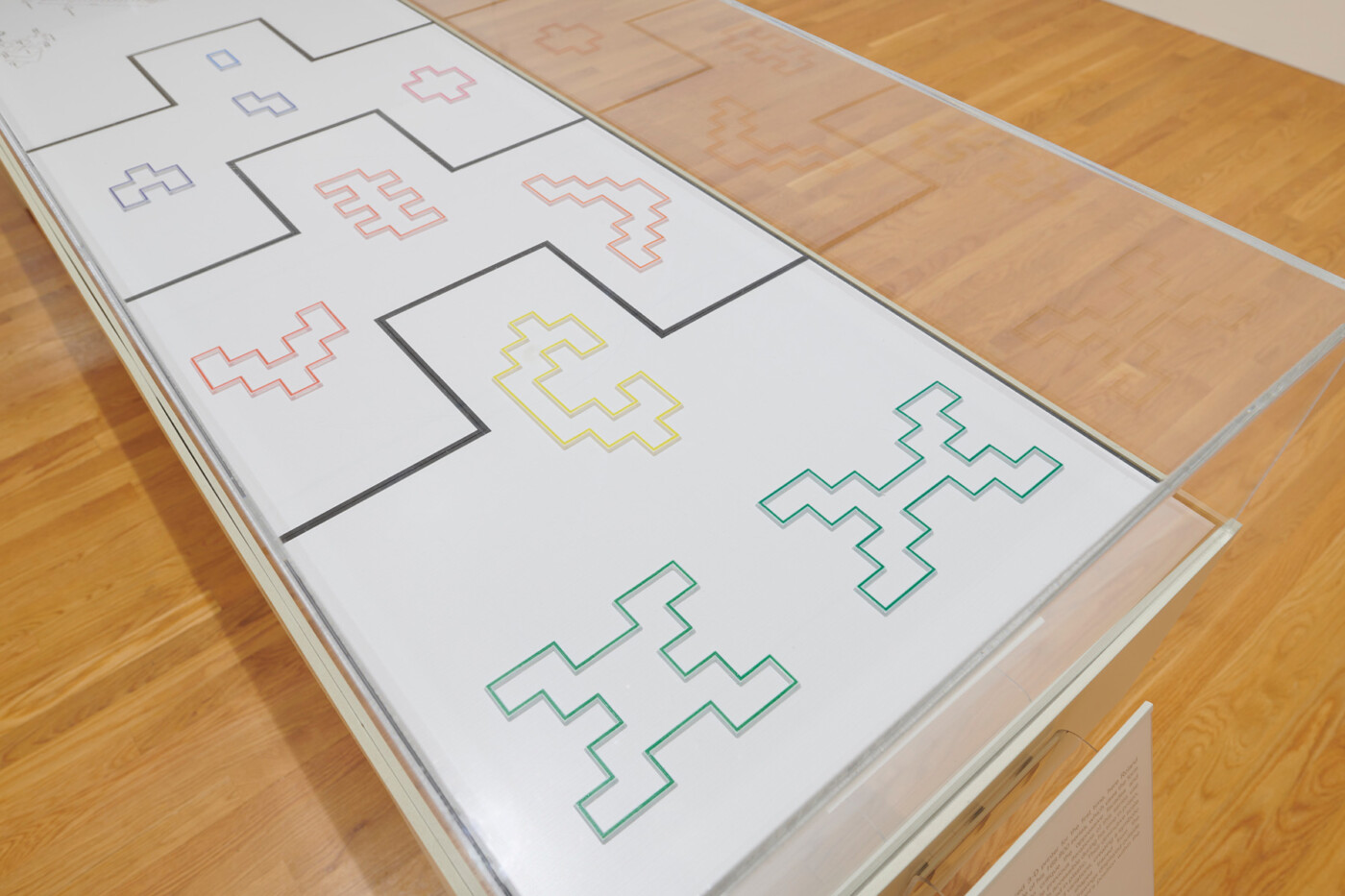

A vitrine in the center of the room contains abstracted maquettes of prison cells created with a 3D printer. The sharp lines convey a rigidness and conformity that’s legible to those who are intimately familiar with prison architecture and how it functions as a tool for disenfranchisement and cruelty. By design, prisons telegraph a violent, visceral, and metaphorical sense of separation; they are, as architecture writer Tom Wilkinson describes, “cloaks of invisibility for the state’s secret human foundations. Within the perimeter of the prison itself, they produce a microscopically subdivided space, consisting of the regular repetition of its most basic element: the cell.”[1] Variations of the cell block recur in these miniature geometric renderings of original, large-scale fabrications Roland produced from steel and enamel, reimagining mortar lines with acrylic resin and Kool-Aid pigment that evoke the circulatory pathways of veins within an organism.

Processing Systems finds Roland fusing art and technology, thanks to a year-long fellowship through the Duke Artistic Research Initiative Fellows Program. His evolution into abstraction is a departure from his performance-based works that place his body and the institution of incarceration into a hyper-visible public sphere. Previous works similarly acted as a meditation on the systemic social, environmental, and psychological effects of the carceral system–but were also an account of his lived experience with imprisonment.

Days before he was to enroll in his MFA program at UNC Greensboro in 2012, Roland discovered that there was an outstanding warrant for his arrest in Washington DC. The artist was incarcerated in 2013 and served a ten-month sentence; after a protracted legal battle, he won an exoneration, declaring that he was wrongfully incarcerated. Roland struggled with reintegration after his release, and art became his primary tool for processing and communicating his experiences, examining the ways identity is shaped by his three-year entanglement with the criminal justice system and the psychological toll incarceration takes on mental health. His experience inspired his groundbreaking and deeply introspective Jumpsuit Project (2016-2017, ongoing in different iterations), wherein Roland wore an orange jumpsuit every day during his senior year at UNC Greensboro through Graduation Day. His subsequent call-and-response project, titled After the Wake-Up and exhibited at CAM Houston in 2018, excavated the innermost thoughts of incarcerated persons through recreations of hieroglyphs found among wall carvings within prison cells. In this piece, Roland offered prompts to visitors who were encouraged to carve their responses into an installation wall.

Looking to center other wrongfully incarcerated individuals by communicating the intricacies and injustice of their experiences in Processing Systems, Roland turns the concept of portraiture on its end. However, his approach is more oblique; the concealment itself becomes, to borrow a phrase from writer George Yancy in Black Bodies, White Gazes, a “seen absence.”[2]

Through introductory wall text and labels, we only know three things about the subjects and their numerical likenesses: they were exonerated, they were wrongfully incarcerated in federal or state prison, and the time they served is the title of their portrait.

Roland directs the viewer’s gaze to the “seen absence” that asks what can be gleaned from a portrait that consists of digits. Rather than focusing on the individuals themselves, Roland focuses on their circumstances and the systems behind the steel curtain that erase and reconstruct the identities of incarcerated individuals. This anti-portrait refuses the corporeal gaze. Instead, viewers are invited into a game of equations or codes. Roland, by asking the viewer to solve for X, also asks an important question: who does the code serve? Are these portraits a reflection of erased identity, or is he protecting the privacy of his subjects?

As I sat with these aluminum panels, looking at the shaded X’s that appeared on some of the works, I directed my thoughts toward the penal institutions and their web of commercial enterprises that benefit from anonymity and erasure. These entities detach and erase with impunity, creating systems of conformity and compliance that are engineered into every aspect of the prison industrial complex, a term first coined by Angela Davis in her 1998 essay titled “Masked Racism”: “Prisons do not disappear problems,” she wrote, “they disappear human beings. And the practice of disappearing vast numbers of people from poor, immigrant, and racially marginalized communities has literally become big business.”[3]

Alternatively, Roland’s coding could also represent a communication device between himself and his portrait’s subjects, a “seen unseen” existence that is intimately felt by inmates and exonerees alike. For Roland, this gesture is a powerful acknowledgment of presence, of being “seen.” Whether it is a tool of erasure, an affirmation of presence, or a preservation of privacy remains unclear, and that’s very likely the point. The exhibition presents a complex series of codes that are difficult to crack. Still, once you create a fissure, you are invited to take a close look at the unforgiving systems that use anonymity as a tool of subjugation and the circumstances that lie beyond the numbers.

[1] Wilkinson, Tom. “Typology: Prison.” The Architectural Review, May 14, 2021. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/typology/typology-prison.

[2] Yancy, George. Black Bodies, White Gazes: The Continuing Significance of Race. Italy: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2008. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Black_Bodies_White_Gazes/iyoonjqA0Z0C?hl=en&gbpv=1.

[3] Davis, Angela. “Masked Racism: Reflections on the Prison Industrial Complex.” History is a Weapon, 1998. https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/davisprison.