In March 17, 1951 a Scottish cartoonist named David Law introduced a new character into a British comic called Beano, and that character was called “Dennis the Menace.” Earlier that week in the United States, on March 12, a cartoonist name Hank Ketcham enjoyed the first publication of his syndicated comic strip titled “Dennis the Menace.” These men had never met and did not know each other. And yet, this story of two cartoonists creating characters with the same name on different continents five days apart somehow seems less improbable than the first American to hold the position of Master of Drawing at the Ruskin School of Oxford University living out his days in the quietude of Augusta, Georgia. Philip Morsberger (1933-2021) was the first American and overall sixth Master of Drawing at the Ruskin School of Oxford University in Oxford, England, from 1971-1984.1

Morsberger’s impact on the Ruskin School included the creation and implementation of a new BFA program, no small feat at an institution as entrenched in its habits as Oxford University. Morsberger grew up in Baltimore where he studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art, before enrolling at the Carnegie Institute (now Carnegie-Mellon) in Pittsburgh, where his studies were interrupted from 1953-55 courtesy of the U.S. army. His time in the military gave him a taste for life outside America and the G.I. Bill allowed him to pursue an advanced degree at Oxford University in England. Morsberger’s subsequent teaching career was, as wall text states at the Morris Museum of Art, “peripatetic.“2

His first years teaching back in the U.S. resembles that of many young artist academics, with positions at Miami University, Ohio; Rochester Institute of Technology; and Rosary Hill College in Buffalo, New York. In 1971, he returned to Oxford University as the Ruskin Master of Drawing for the next twenty-three years. His teaching career after the Oxford appointment proceeds from mountaintop to mountaintop with visiting artist gigs at Harvard in 1976—when he incidentally converted to Catholicism—and Dartmouth in 1983. This was followed by positions at the University of California, Berkeley (1986-87) and the California College of Arts & Crafts (1987-96). In 1996 Morsberger left California to accept a five-year position as Morris Eminent Scholar in Visual Arts at Augusta University in Augusta, Georgia. When that term ended, Morsberger opted to stay in Augusta with his family until the time of his death in 2021 from complications caused by COVID. He lived out the last twenty-five years of his life in Augusta, Georgia, where he painted in his studio, blocks from the Savannah River, every day. And yet, in many ways he and his work remain a public mystery.

In April 2024, two Augusta galleries presented simultaneous exhibitions of Morsberger’s work. Candl Gallery held an exhibition of oil paintings and oil pastel drawings selected by the artist Ed Rice. Westobou Gallery presented an informal but thorough assortment of Morsberger’s drawings in their Micro Gallery. These dual exhibitions provided a useful introduction to an artist who could be described, as Balthus said about himself in a 1968 telegram to London’s Tate Gallery, “…a painter of whom nothing is known.”3 With Morsberger, there are always two things to address at the onset. The first being his curriculum vitae, a case study in career improbability. His 2007 monograph included “appreciations” by his Oxford classmates William Tucker and R.B. Kitaj, as well as one from Priscilla Tolkien, the youngest of J.R.R. Tolkien’s children. The second question is just what was he doing in his Augusta studio, so quietly and for so long. His work is absent from major collecting institutions in Georgia, except for the Morris Museum, and reviews of his work are sparser than one would expect.

The exhibition at Candl Gallery included eleven easel sized paintings and six oil pastels on paper from 1984 through 2011. It was not uncommon for Morsberger to work multiple years on a painting and at least one example, Supplication (1996-2008), took over twelve years to complete. Morsberger begins these paintings with clusters of loose, urgently scrubbed patches of color he puts down as a back wall for the shallow pictorial space. Morsberger’s expressionism comes mostly from the elbow, not the long, embodied swaths of the Abstract Expressionists. It is the broth into which his figures get introduced, a reminder that no painting starts from blankness. Morsberger may have felt the seduction of abstraction and the usefulness of its methods, as any painter who experienced art of the 1950’s and 1960’s might, but he rarely made fully abstract work. Morsberger’s paintings suggest that, for him, true communication with an audience ultimately requires the vehicle of representation to do so. Morsberger’s method of representation is not based in the mimesis of the atelier model that he learned, then taught.

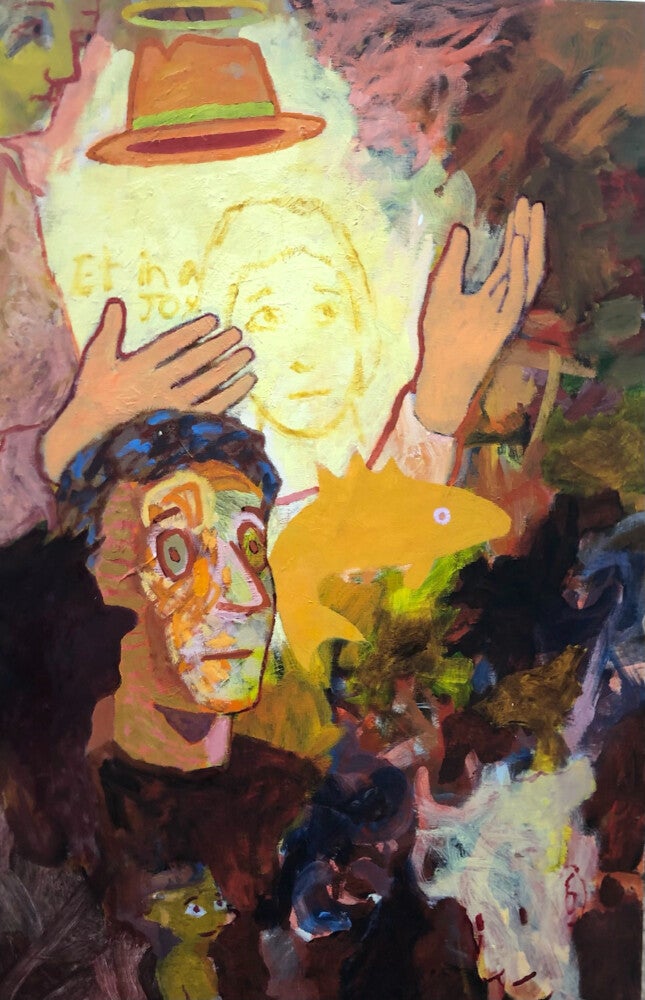

The anecdote about the origins of “Dennis the Menace” was not entirely arbitrary. Morsberger’s representational style is shaped by the comics of his youth, such as Little Orphan Annie and Gasoline Alley, both featuring orphans and fathers. Thus, the figures in Morsberger’s painting have the schematized faces and pantomimed gestures that come from puppet shows, silent films, and the history of comics. Morsberger was known to be a devout Catholic who attended mass nearly every day. It is tempting to read his comic-book derived figures as, as stated in Vatican II, a message delivered in the “local vernacular.”4 However, what we see most often is a private metonymic code where images of hats are meant to represent the artist’s father, while anthropomorphic dogs indicate his most wished for pet. 5 Morsberger’s characters are usually in the midst of action, even if it’s an unexpected or mysterious action.

Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist.

In Blythe Spirits II (1984-2005), a gray-haired man dressed in black with enormous hands puts out a cigarette on the left edge of the canvas, a gesture so odd that it’s difficult to recall ever seeing it before in a painting. In Family Group (2006-2009), the large red hand of the father figure looms over the cowering younger man while the fully dressed dog rushes forward past a distant mother. In La Barricade (2006-08), the sailors gesture upwards in shocked awe at something viewers cannot see. These are not neutral actions, and Morsberger appears to have absorbed the subjective tendencies of painting from the 1980’s. His best pieces can conjure theatrical grandeur in the manner of early Sandro Chia, and his most densely packed paintings echo the doomed dancefloor aesthetic of Jorg Immendorf’s Café Deutchland paintings.

Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist. Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist.

Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist.

One painting in the Candl exhibition that shows Morsberger’s capacity to utilize all his formal tools to present a legible message is in Tick-Tock (2005-06). In it, there are six male figures partially displayed, all with the shaved heads and camouflage uniforms of the military. These characters are rendered with some of Morsberger’s quickest, loose-limbed brushstrokes. One lone soldier has his mouth open as if speaking, and it’s that soldier who holds a paint brush and may be the artist himself. In the foreground is a soldier with one of the most fully rendered items in the entire painting: a wristwatch. Any depiction of soldiers marking time will undoubtedly reference the contingencies of military life, where at any moment one may be called to enlist, called to duty, or called to war. It could just as easily be warning that the impending end of life approaches with the same propulsive certainty of the wrist-watch’s ticks and tocks.

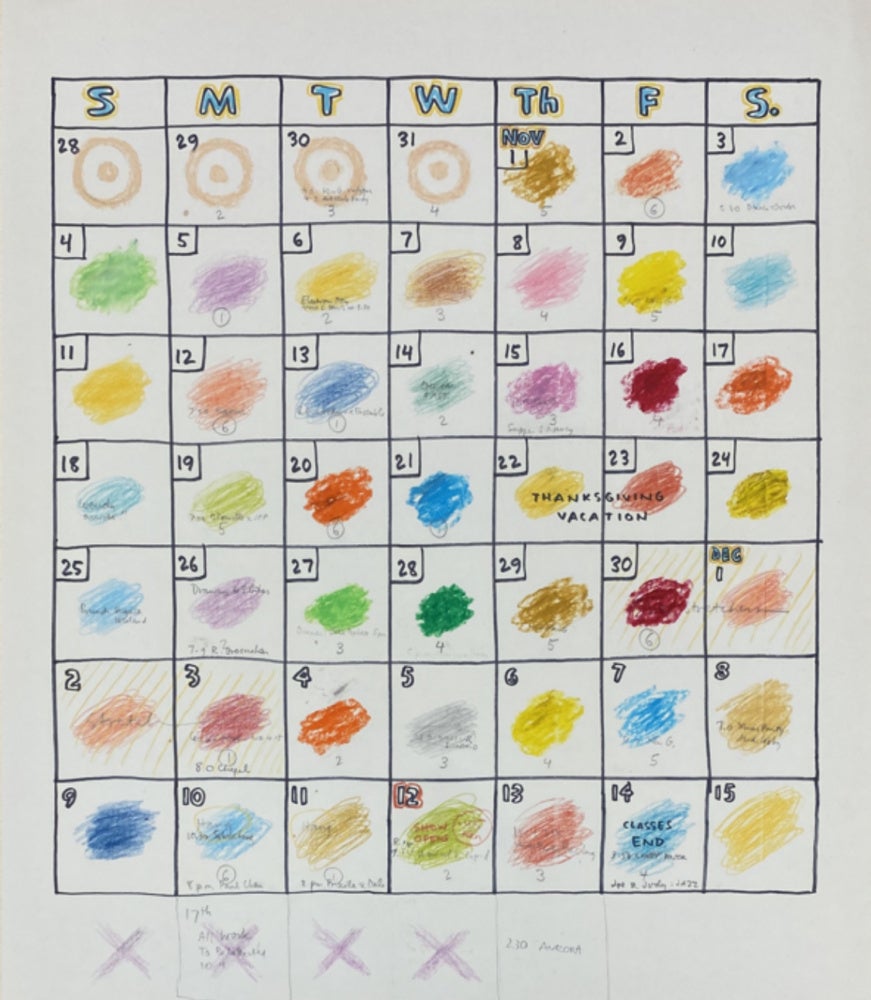

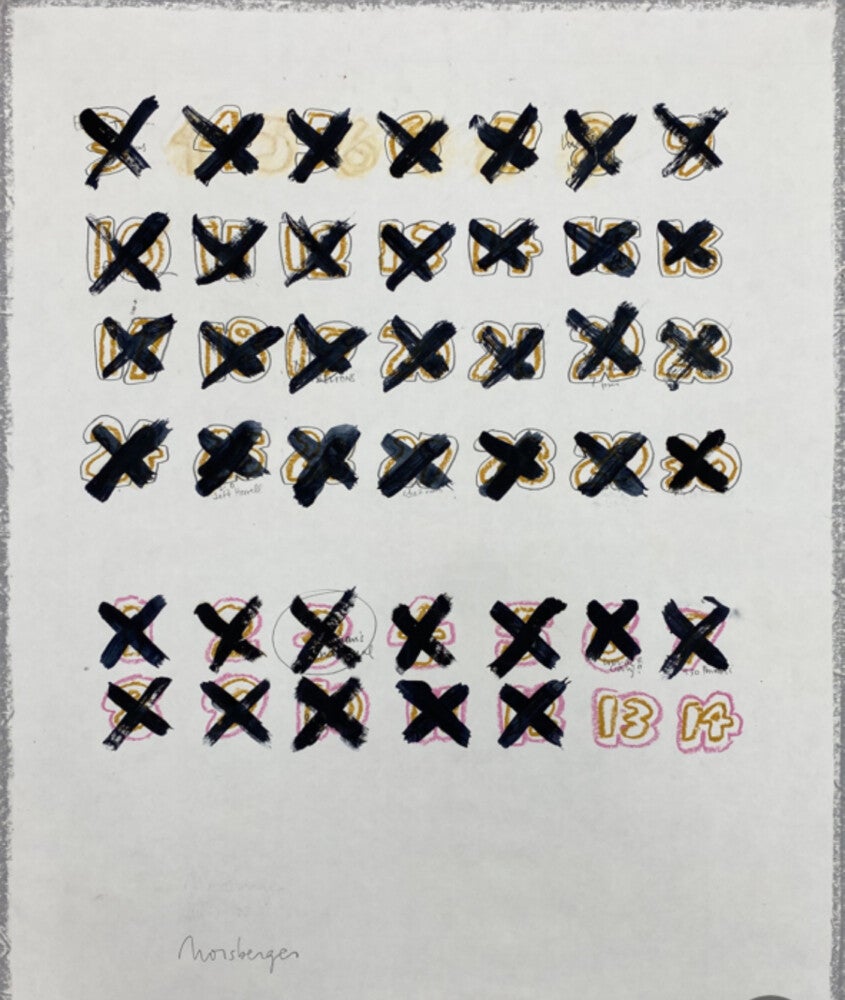

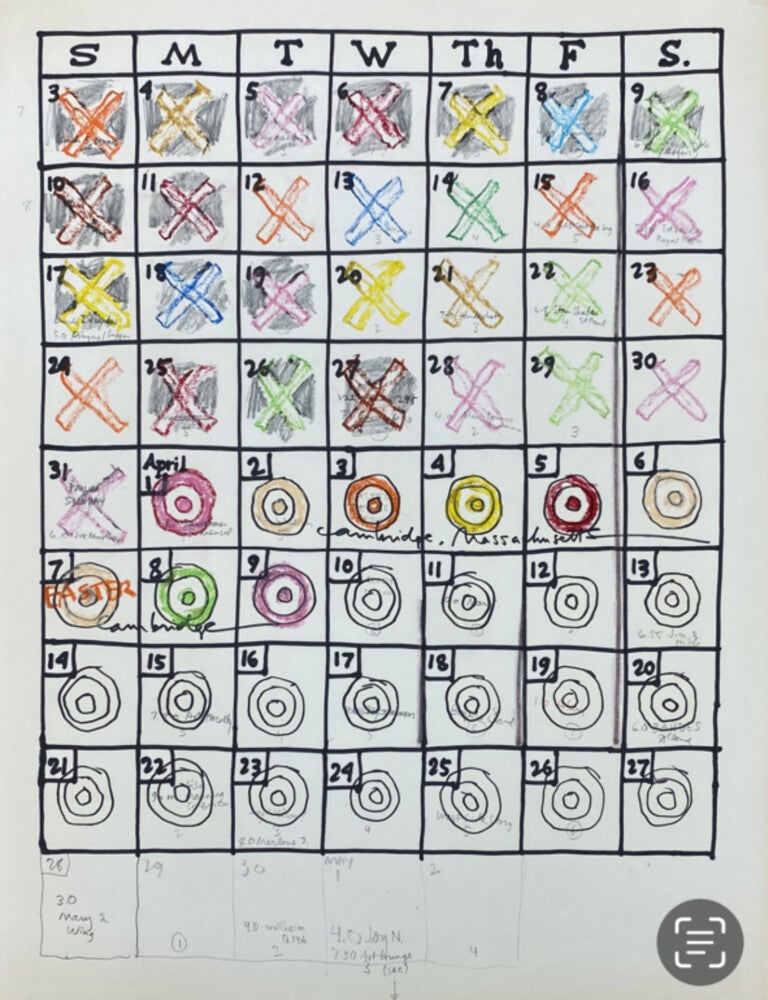

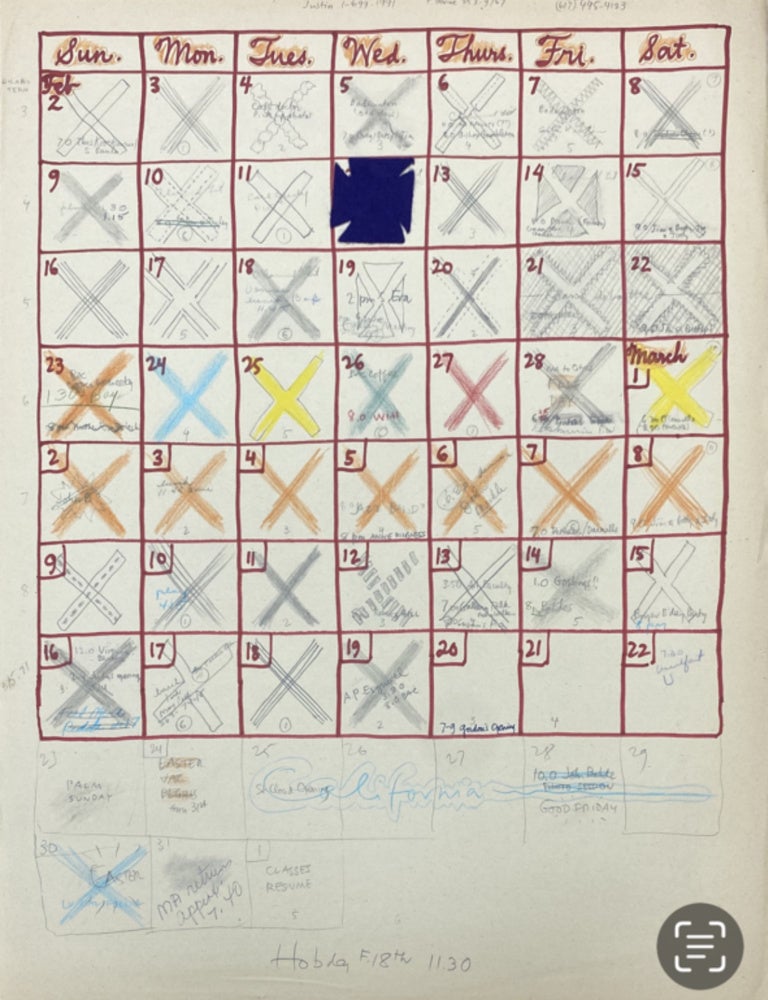

The works on paper shown at Westobou Gallery give a very different side of Morsberger. There were stacks of academic figure drawings in various stages of completion, many of which had the look of instructional demonstrations straight from the classroom. A greater surprise were the so-called “calendar” drawings that Morsberger made late in his life. Morsberger apparently created home-made gridded calendars to plan out his months. He may not have considered them to be discreet artworks in their own right, and this “non-art” assignation may be what permitted the imaginative freedom of their construction. There appears to be a loose color schema in mind at the start of each calendar drawing, which Morsberger then populated with functional notations, intuitively drawn and written. It was the place where his art and his life braided together the most effortlessly, where the abstract grid coexists with relaxed, often fully chromatic mark making. These drawings have affinities with On Kawara’s date paintings or Alfred Jensen’s gridded numeric orders, but strongest and most unexpected peer artist may be Hanne Darboven’s obsessive daily accumulations.

Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist.

Image courtesy of Candl Gallery, Augusta, Georgia and the artist.

Morsberger’s work operates across contradictions. For someone who distinguished themself through drawing instruction at Oxford, Morsberger did not utilize representational drawing for his mature work. He did not make preliminary sketches and did not maintain a sketchbook. The single artist statement attributed to him in the Candl Gallery show mentions color seven times without mentioning drawing at all. The first moves in his paintings were always abstract colors, while the last moves relied on sequential art techniques from the comics of his childhood. Yet, the comfortable familiarity his characters invoked belied interior drama not readily accessible through casual viewing. Morsberger’s works are best experienced, like the diary of an anchorite, slowly through time.

- [1] https://www2.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/212075/Ruskin-School-RS.pdf ↩︎

- [2] Wall text. As Others See Us / As We See Ourselves: Artists’ Self-Portraits from the Permanent Collection. Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, GA. January 10 – June 20, 2024. ↩︎

- [3] Beckers, Julie. “Balthus Retrospective.” Studio International. November 24, 2015. ↩︎

- [4] Second Vatican Ecumenical Council. “Constitution on the Liturgy,” Art. 36:3. Mar 5, 1967. ↩︎

- [5] Lloyd, Christopher. “The Art of Philip Morsberger: Astride the Atlantic.” Philip Morsberger. Merrill Publishers. 2007. p. 13 ↩︎