At the heart of the High Museum of Art’s exhibition, Patterns in Abstraction: Black Quilts from the High’s Collection, is the long-contested question about the relationship quilts have with the larger genre of abstraction. The High’s position is made clear: Quilters are abstract artists and Black quilters are essential to understanding the history and innovation of the medium. Yet, the stories within and among the quilts, perhaps unintentionally, speak beyond a mere debate of art history and instead ask,“What is community, what is legacy, what is warmth?”

An answer is offered in the sheer presence of so many quilts that demonstrate diligence and care that transcends utility. Nearly twenty quilts, created over the span of a century by Black women quilters, mothers, community leaders, and artists, hug the walls of the Wieland Pavilion’s Lower Level gallery. Several of those quilters are from Gee’s Bend, an isolated Black community surrounded on nearly all sides by the winding Alabama River. Renowned for their craft and artistry, works by notable women from the community are included in the exhibition, including Lucy T. Pettway, Louisiana Bendolph, and Annie Mae Young.

It is the precision in Pettway’s 1981 work, Birds in the Air, that captures the essence of artistry and craft central to the argument of the exhibition. It is a large but light quilt with energetic diagonal triangles of yellow, black, red, and purple flying across the surface that contrasts with a larger pink triangle towards the bottom right corner. Positioned squarely at the entrance of the gallery, it is a statement to every viewer about the duality that quilts embody in the study abstract art, both as contributions to the genre, but also as “textiles with testimonies”, as the High’s Coordinator of Gallery Experiences, Hannah Amuka, refers to them.

The quilts are a testimony. Testimonies of legacy and lineage. The stories of the textiles in Gallery 100 reference the interconnectedness of Black women artists, both through the function of the quilt itself, and through the creation experience it offers a community. While Gee’s Bend was a physical community in which a number of artists created, lived, and practiced, it is their work that speaks on its own behalf. It is Louisiana Bendolph, a fourth-generation quilter, saying “she’s alive in that quilt” after seeing her grandmother, Annie E, Pettway’s work in a Houston museum in 2002. Legacy is that moment spurring her back into her own quilting practice, creating works like Blocks and Strips Medallion (2003) showing that she remains committed to traditional quilting styles.

Two of those styles are highlighted prominently in the exhibition, specifically Birds in the Air and Housetop. Two patterns representing home and nature, domesticity and wilderness, initially exist as opposites, but within the context of the exhibition, pair together as testaments to quilts solid positionality inside abstraction. Long before the genre debate, Maker Once Known explored these abstract styles as shown in Birds in the Air Variation (1930s), a large quilt with blue triangles, titled in a way that feels akin to the ballet terminology, representing a solo interpretation of a well-known artwork.

Housetop Sampler (1910s-1920s), and Multiple Housetop (1920s), both by Makers Once Known, present the viewer with true individual artistry that flourished in the community of creatives.

Maker Once Known, Untitled, ca. 1910s-1920s, cotton. Image courtesy of High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Corrine Riley on the occasion of Collectors Evening, 2017, 2017.182.

Extending legacy beyond formal tradition, the exhibition moves to ask the viewer what of legacy, if it is not remembered? Quilts as memorials are explored, namely through “Lazy Gal” Work-Clothes Quilt (2002) by Annie Mae Young. The quilts that are made with what is often considered scape fabric, repurpose rather than discard material. Young’s quilt created with worn denim establishes connections across materials in order to preserve. To conserve memory and presence, she quilts together clothes of a male relative who no longer wears them. It offers quilts, beyond their role as artworks, an opportunity to serve as a memorial of those who are no longer alive.

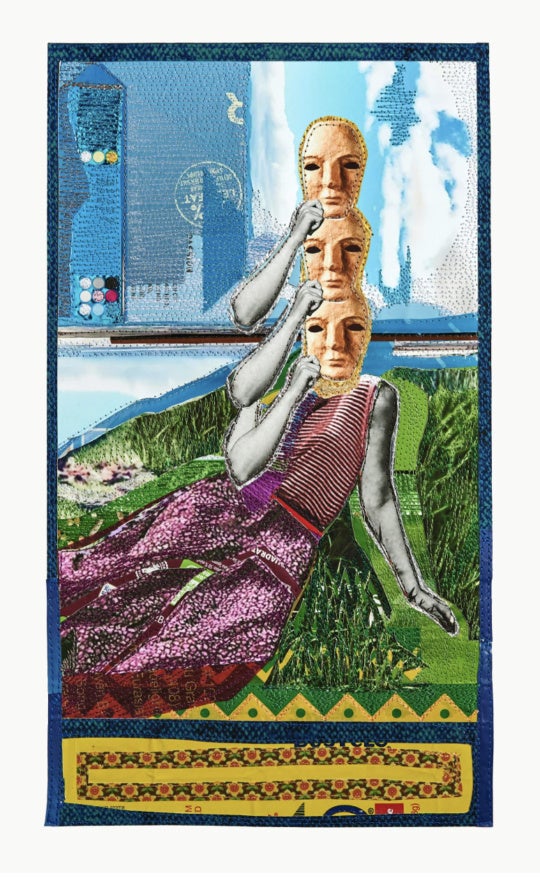

In addition to memorial, several of the works serve as an homage to past quilters and traditions. There is also homage while riffing, and sometimes riffing into oblivion with extreme novelty and innovation. Yvonne Wells’ B.B. King Concert in the Garden (2019) connects to the traditional pattern of Birds in the Air, but uses literal birds rather than shapes. The rest of her quilt aims to reimagine an event without hinging herself to realistic depictions. It uses textiles and unexpected fabric choices to capture a moment, but she brings to it an otherworldliness that separates this quilt from the rest of the works in the exhibition. Homage wells up again in Awestruck Before an Unforgettable Nubian Queen or From Gee’s Bend to Royalty (2021) by Carolyn W. White, which recreates a famous photograph of a young Black girl admiring Michelle Obama’s portrait and places its imagery into the context of quilting. The work addresses intergenerational inspiration between Black women.

While the High is arguing that quilts belong in abstraction, perhaps the exhibition left me considering whether quilting is too rich, too connective, too layered for the limitations of a genre. Quilts cannot be disconnected from their original purpose: warming the people loved most by the creator. They also provide a connection between the artist and their environment. The most important lesson, though, is about interconnected. Quilting is an art forms in which those cross-cultural, intergenerational understandings of art, craft, and history truly come alive. The legacy of art and perhaps all creative work reverberates across generations.

The connection the exhibit makes between quilts and the work conventionally considered to be abstract is loose, and the works aren’t framed around what makes them the same as other abstract works. Perhaps it doesn’t need to say that. What is present is the continuity of family and artistry. The pulse between each work is a question of memory and relation, between works, between artists, and between eras. The exhibition proposes that memory itself is the true legacy of quilting. Memory connects, deepens, and sustains the relations we need to survive.