If it weren’t for Hamza Walker’s 12-year-old daughter’s proclivity for Young Adult Fiction (YA), the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center’s latest exhibition “Teen Paranormal Romance” may not have happened. As the story goes, Walker—who is curator of the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, where the show debuted in March—was led down the aisles of a Chicago Barnes and Noble by his daughter, to the section containing the object of her pursuit: Veronica Roth’s dystopian hit novel (now Hollywood movie) Divergent. As he stood in the YA section, surrounded by melodramatic novels containing stories of sexy vampires and post-apocalyptic worlds, Walker realized that this particular aisle was labeled “Teen Paranormal Romance,” a burgeoning segment of the increasingly influential YA market. Walker had an “a-ha” moment; the title of the show preceded the show itself.

Walker recounted the story to BURNAWAY as he was installing the exhibition, which opened to the public on October 25. Despite the purported subject, you will not find depictions or direct references to the likes of Katniss Everdeen or Harry Potter at “Teen Paranormal Romance.” For, Walker was more concerned with the psychological and cultural drives behind this recent trend in YA novels.

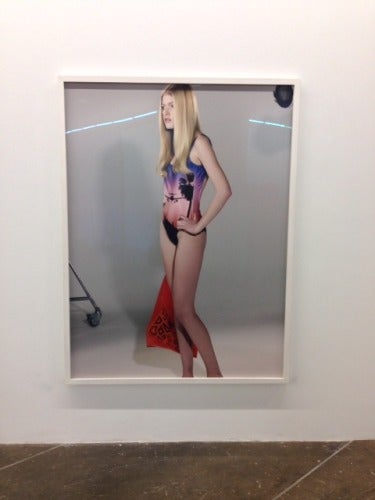

Opening one of five large rectangular cardboard boxes, Walker extracted a mattress boasting an abstract, psychedelic print, a product of the decade-long collaborative effort between two big-time New York artists, Wade Guyton and Kelley Walker (called GuytonWalker). He was going to place them near Roe Etheridge’s Louise with Red Bag (2011), a photo of a thin blonde adolescent girl, maybe around age 15, wearing a bathing suit that bears the printed image of an airplane landing in a tropical urban destination (Miami, perhaps). Evidence of a photo studio, indicated by the fall of her shadow against a white backdrop and lighting, confirm her role as a model.

Walker noted that the relationship between the works was “obvious,” and gave a rather cryptic explanation about the “psychosexual” dialogue that would be created by placing the mattresses next to Etheridge’s photo. Obvious? Well, maybe. For many viewers, their correlation may seem a tad bit dubious. But for Walker, that’s kind of the point.

After curating a number of exhibitions that were pretty straightforward—like “Several Silences” in 2009, which explored the sundry social and aesthetic interpretations of silence in contemporary culture; or 2007’s “Meanwhile in Baghdad…,” which, plainly put by Walker, “was about war”— he wanted to do something with a heavier dose of ambiguity. “Teen Paranormal Romance” surely delivers by not delivering any spoon-fed explicit theme. Well, at least not too easily.

Nevertheless, I like a challenge, so bear with me while I take a jab at this apparent relationship between GuytonWalker’s mattresses and Etheridge’s Louise with Red Bag.

Everything about the superficial idea of Louise ostensibly should be regarded as fairly provocative and “hot”: the young body, the aloof gaze, the healthy blonde hair, and the bathing suit. But, in a way, she’s anything but. Maybe it’s due to the work’s designation as “art” rather than “advertisement,” but Etheridge’s image comes across as a diluted re-presentation of the hyperreal. There’s an unappealing artificial quality to Louise, who is drained of any conceivable sexuality, and frankly is a bit awkward; the only discernible sexuality might just be the image we have of Louise as a sign of a societally constructed image of sexuality.

Louise isn’t just selling fashion, she is fashion—she and the red bag are more ore less interchangeable. And, fashion is inorganic – it’s applied color and cosmetics and mass-produced garments; fashion is ornamentation, it’s feminine; it’s a fetish whose purpose is solely to be repeatedly consumed, disinvested, and consumed (a cycle that correlates to the Freudian death-drive). Consumerism demands the novelty of that which is constantly changing, so the cycle of fashion is particularly resonant within the construction of capitalist consumption, where exchange value defeats use value, where commodities function more as signs that organize value and desire. The objects that express and embody these material goods—like a pretty young model or a trendy bag—then take on a role analogous to something like a secular fetish.

And, what does a mattress suggest? Three words off the top of my head: sex, dreams, and death. In a way, each of these three words can then be translated as: pleasure, unconscious phenomena, and the termination of life and/or the drive to destruction. As I touched on, in a consumerist economy, the drives are diverted from their aims and toward artificial needs – needs that fail to truly feed any desires, nor accomplish legitimate pleasure. As soon as the object of consumption is invested, it is dis-invested. For, consumers must not become attached to their objects: they must consume, precisely by sundering themselves from them, by destroying them, and by disposing of these objects in order to follow the diversion of their libidinous energy emulating from their drives towards ever-newer objects propelled at them by industrial innovation. Hence, death can be seen as a metaphor for the annihilation of an object (upon an event like the arrival of its upgrade into the market). For this compulsion to continue in a relatively smooth fashion, it must be repressed by the unconscious.

As for the rest of the show…

In a smaller gallery is Jack Lavender’s Crystal Grapes (2012), where two crystal grape bunches hang from a grid of rusty rebar. Crystals have long been associated with New Age countercultural movements, invocations of the feminine and wealth, and ideas of transparency. Having crystals shaped as food, specifically in the form of grapes—a fruit that carries with it symbolism of the bacchanal and the desire for abundance—alludes to their potential to be consumed. To Walker, the grape bunch of crystals are the “paranormal part of the piece.”

Ed Atkin’s video Even Pricks (2013) is playing in a darkened gallery. In this eight-minute video, configured in Atkin’s typical hyperreal style, the thumbs-up symbol becomes a central motif (the connection to a Facebook “like” is unmistakable). Using high-definition CGI, the artist inflates the thumb to the point at which it seems ready to pop, and then allows it to deflate until it appears flaccid, defeated. It is also seen reversed into a thumbs down, which is inserted into a pool of Yves Klein Blue, an eyeball, and a bellybutton. A chimp moves its mouth and speaks like a human, a scene that perhaps indirectly asks, what does it mean to be human?

The ACAC’s largest space is occupied by an installation by Los Angeles artist Kathryn Andrews. Titled Friends and Lovers (2010), the piece includes an aggressive chain-link fence offering no entrance, so visitors can only walk around it. Inside, two whitewashed cinderblock walls face each other, each with an identical (bear? chipmunk?) black cartoon head, smiling at each other in a strange fashion. The installation puts the viewer in a voyeuristic position, gazing at a static interaction between the two characters. Are the cartoons meant to be perceived as a simulacrum for human relationships, governed by coded gestures and inauthenticity? Because cartoons exist in the world of the digital and the screen, and in consideration of the chain-link fence, Friends and Lovers suggests a conditioned desire for the unattainable and the emptiness found in the virtual world.

Hanging on the walls surrounding Friends and Lovers, as if observing the observer, are Chris Bradley’s Grease Face #3 and Grease Face #4, smiley faces made from soiled pizza boxes (both 2011), and Jack Lavender’s wall assemblage Hannah (2012), comprising materials like dried limes, posters, sand in a bottle, sugar packets, empty energy drink bottles, and air freshener. They all have a sort of trash aesthetic, whose parts are found within a teenage American wasteland.

Jill Frank’s photograph Bong (Shawn), 2014, of a young man about to guzzle from a beer bong, is in a far corner of the same gallery. On the floor in front of it stands Lavender’s large-scale, erect sculpture Fantasy Line (2013), a large piece of bent steel with the energy drink/sexual stimulant Magnum and a potato chip box attached. Walker created a connection between the two works thematically as well as formally, the bent rod mirroring the co-ed’s bent elbow.

In planning the exhibition, Walker was interested in creating a dialogue between Surrealism (particularly the group’s preoccupation with the unconscious) and today’s popular culture. Through the frame of “Teen Paranormal Romance,” the unconscious is referenced only by way of its absence, masked by a machinelike, programmed existence that feeds the needs of consumerism and popular culture. “Between its palpability within the realm of popular culture, and its abandonment by visual artists,” writes Walker in the exhibition’s essay “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” “the unconscious, as an internal psychic space is a derelict playground where there are no children, only weeds.”

The exhibition’s entry features a large blue and white Op-artlike mural with the show’s title written in a frenzied font. Walker, laughing, revealed that he had no part in its creation (it was designed by Atlanta artist Kevin Byrd). But, he definitely digs it: “I mean, if you’re going to do it, do it. In Atlanta, man, they really put your shit it a push-up bra.” Right on, Hamza. Right on.

“Teen Paranormal Romance” is on view at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center through January 17, 2015.

Jacquelyn O’Callaghan received an MFA in art criticism and writing from the School of Visual Arts in New York and is BURNAWAY’s editorial intern.