© Nick Cave, Photo: James Prinz Photography

In 1992, the artist Nick Cave created his first Soundsuit—part sculpture, part costume—in response to the acquittal of four white Los Angeles police officers who were videotaped brutally beating Rodney King, a Black man. Cave has spoken about feeling protected and empowered by the Soundsuit, which made his race, his gender, his class, and other identifiers indiscernible. “When I was inside a suit, you couldn’t tell if I was a woman or man; if I was black, red, green or orange; from Haiti or South Africa. I was no longer Nick. I was a shaman of sorts,” Cave said in a 2009 interview with the New York Times.

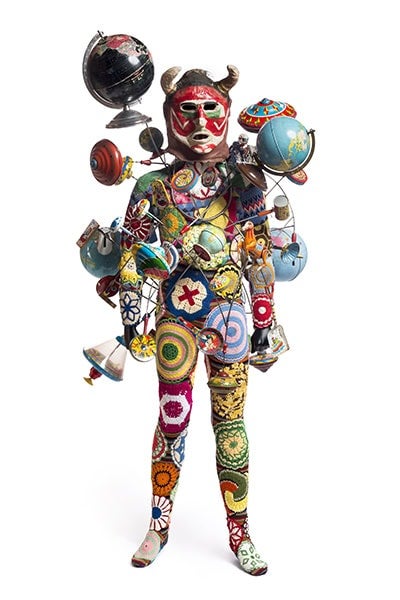

Since that first twig Soundsuit, Nick Cave has crafted over five hundred Soundsuits, ten of which are currently on view at the Mississippi Museum of Art as a part of his exhibition Feat, which originated at Nashville’s Frist Art Museum in 2017. The Soundsuits on view at the Mississippi Museum of Art were made using quotidian materials: textiles, beaded and sequined garments, and wires, along with found objects including sock monkeys, crocheted hot pads, buttons and old toys.

As Cave intended, it is difficult to discern the race of whomever wears the Soundsuit, as most of the Soundsuits cover everything but the wearer’s hands and the heels of their feet. Notably, the mannequins on which the Soundsuits are displayed are generically black. Though the wearer’s body is obscured, however, racial identity is not absent from the Soundsuits themselves.

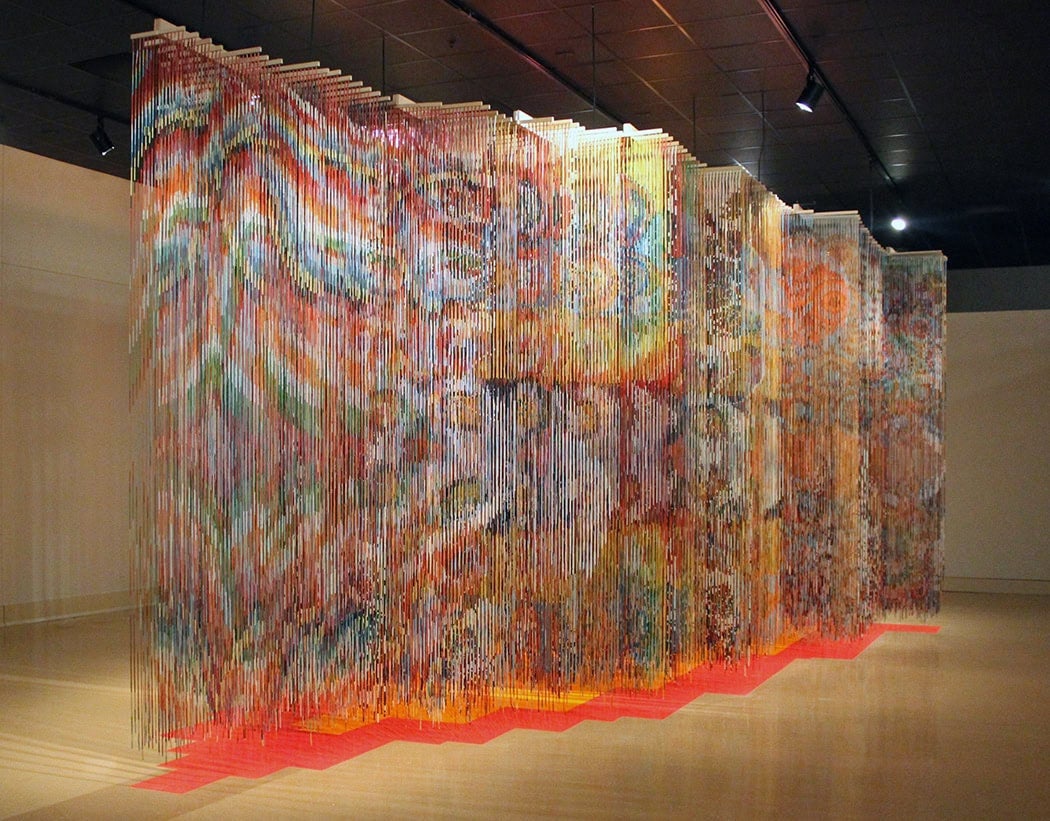

(Photograph by David Sprayberry. Courtesy of the Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson.)

For instance, one suit includes an image of Superman. Though he is an alien, both Clark Kent and Superman read as white. If, as Toni Morrison said, “In this country, American means white…everyone else has to hyphenate,” it stands to reason that the American way, as presented in Cave’s chosen images, is always-already white. That same Soundsuit depicts white children—a blue-eyed, blonde-haired girl and a brunette boy—on the sleeves. One side of the Soundsuit reads, “Love one another,” but the images associated with “one another” do not include any non-white people.

In another suit, made in 2016, the wearer is covered in a bodysuit made of connected, crocheted hot pads. Multiple globes and vintage toys, many of which depict white men and women dancing and partying, are connected with a wire frame. This assemblage orbits the crotched bodysuit like a constellation. The Soundsuit has a papier-mâché mask with a red, white, and green painted face, white horns, and dark-skinned neck and ears. The mask appears to depict a Black person with horns wearing a mask—there are layers to the way in which this Soundsuit conceals the wearer.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2016; mixed media, including a mask with horns, various toys, globes, wire, metal, and mannequin, 84 by 45 by 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Nick Cave, Photo: James Prinz Photography

Cave’s idea to protect himself from state surveillance (and violence) through artistic masquerade would prove prescient. Nevertheless, in hiding his Blackness and covering himself with images of whiteness, he risks tacitly supporting white supremacy: he allows whiteness to be seen, to be exalted, while Blackness is absent. In Cave’s efforts to hide himself, he inadvertently props up whiteness.

The Soundsuits are not Cave’s only works in the exhibition that comment on race. Blot is a nearly forty-three-minute-long video in which someone wearing an amorphous Soundsuit made of black raffia moves and dances in front of a stark white background. The sound that the raffia makes as it grazes the surface of the ground is heard throughout the galleries containing the exhibition. The sound is almost like running water, a stream or a river. Occasionally, feet peep out through the raffia—Black feet; a Black dancer carries the weight of the suit. For nearly an hour, the covered dancer fluidly moves without staying too long in any one shape or form. In Blot, because the Soundsuit is being worn, it is alive, it is in motion. Despite the weight of the seemingly heavy garment, the dancer’s wide, expressive movements convey a mysterious sense of joy. Similarly to a Rorschach test, Blot invites individual interpretation.

Another work, Wall Relief, comprises four large-scale panels that are completely covered in items Cave found at flea markets and thrift shops: strands of crystals, afghans, ceramic birds, figurines of fruit, painted metal plants, gramophones, a golden nativity scene. Though Cave’s written intent was to repurpose discarded and forgotten items and give them new life through his own associated memories, what is most striking about Wall Relief is how it seems to reflect (and critique) overproduction and overconsumption. In works such as this one, Cave speaks to the ways in which consumer capitalism hinders personal growth and free expression. In Cave’s sculpture Untitled, the form of a human arm is visibly weighed down—literally oppressed—and nearly completely hidden by piles of towels, representations of repetitive labor.

Though Cave is primarily associated with his works created in response to police brutality, he appears most convincing when commenting on the ways in which racism and capitalism are inherently intertwined in America. Black Americans are disproportionately effected by disease-causing air pollution; Black Americans are expected to work and provide labor without their faces being seen, their voices heard, or their humanity acknowledged; and, like one puts on and takes off a costume, aspects of Black American culture are blatantly and blithely appropriated.

Nick Cave: Feat is on view at the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, Mississippi, through February 16.