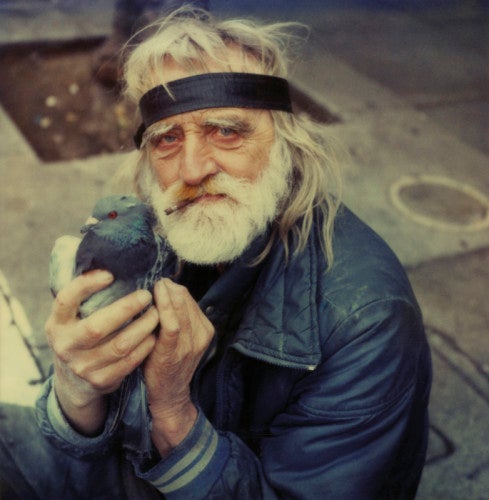

Mike Brodie was given a Polaroid camera in 2004, and shortly after left Pensacola, Florida, at the age of 18, to travel the country. He spent five years hitchhiking and jumping trains all over the country, creating an archive of documentary photographs between 2004 and 2008. Brodie—a.k.a. The Polaroid Kidd—lived in Nashville for a time and graduated from Nashville Auto Diesel College, which is now, fittingly, called the Lincoln College of Technology. I write “fittingly” because Brodie’s great theme is the transience of faces and places over time—reminding the viewer that all photographs are of the past, and often the lost. People leave home, colleges change their names, and even a gifted artist like Brodie has ended up putting down his camera in order to be a mobile diesel mechanic in Oakland, California, where he works out of his ’93 Dodge Ram.

Although Brodie has quit making photographs, Twin Palms has just published images he made between 2004 and 2006 in a seeming-elegiac new tome, Tones of Dirt and Bone, which serves as a kind of prequel to the photographer’s breakthrough monograph, A Period of Juvenile Prosperity (Twin Palms, 2013). Brodie’s studied portraits and landscapes reveal quite a precious sensibility, especially given the limitations of Polaroid photography. The images have a ritualistic quality, bringing a crackling intensity to the melancholy happenings he documents.

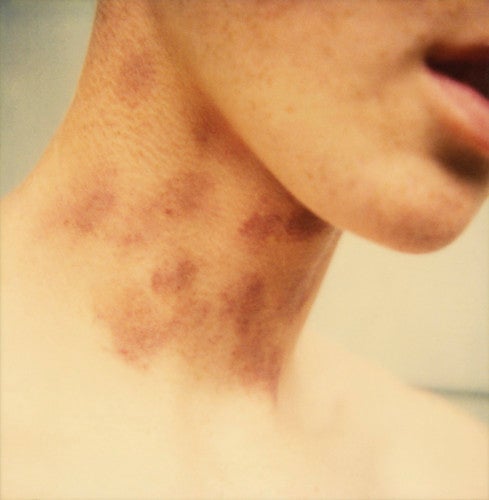

The people in Brodie’s portraits don’t smile much. They don’t snarl or frown much either. They mostly stare at the camera the same way you might stare at the horizon from the top of a boxcar with your world in your pockets and a face full of wind. The woman depicted in Accident smiles just enough for the close-up shot to capture her missing front teeth and her scraped cheek. Her face is framed in the furry hood of an Eskimo coat and it’s hard to tell whether her blue lips are bruised or painted or cold. The little boy in Ayvn. Pensacola, FL also stares at the camera, yet he is hiding behind his mother. Only her arm is visible—it’s decorated with a tattoo of children holding hands as they dance in a circle.

Brodie’s haunted faces reflect the haunted places he’s traveled through. His landscapes are sometimes anxiety-inducing in their expansiveness, which is exaggerated by the height and speed of his train-top perspective. When he’s on his feet, some of that novelty is gone, but Brodie still manages to capture the melancholic sensation of passing time, as in the image of a foggy alley in Olympia, Washington.

The photographs in Tones of Dirt and Bone were shot with Polaroid’s Time Zero film, which was phased out between 2005 and 2006. The film was named for its faster-developing chemicals, producing images with richer, brighter colors. Come to think of it, “Fast and Bright” would be a pretty good name for a quick-lighting candle—the kind that Brodie or one of his traveling companions might burn at both ends.