The dead have told these stories / To the living.

—Frank Stanford, “The Light the Dead See”

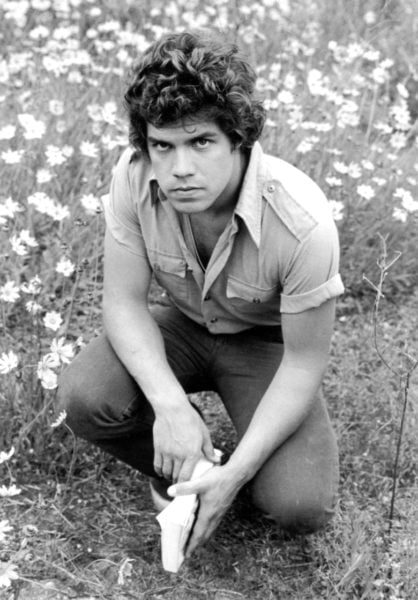

The title poem from his first collection, “The Singing Knives” is what I recommend to readers new to Frank Stanford because it offers a glimpse of all the poems that followed: mad characters (“Jimmy ran down the road / With the knife in his mouth”), startling images (“When he cut a throat / It was like Abednego’s guitar / And the blood / Flew out like a quail”), and a sensual reveling in pure sound (“I dreamed I trailed a buck from Panther Brake to Panther Burn / I dreamed the Chickasaw slit his throat in the pawpaw”). Its psychedelic verbal sprawl hints at the epic scale of Stanford’s masterpiece, The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You, a 15,283-line poem first published in 1977 but which Stanford is rumored to have been working on since he was a teenager at a Catholic boarding school in Arkansas in the 1960s.

Part Romantic, part Gothic, part Symbolist, all Southern, Stanford’s poetry captures a dark, magical reflection of the borderlands between the Ozarks of Arkansas and Memphis, Tennessee, where he grew up and established himself as an ambitious, emerging poet in the 1970s. In 1975, along with poet C.D. Wright, Stanford founded Lost Roads Publishing in Fayetteville, Arkansas, aiming, in his words, to “reclaim the landscape of American poetry.” In June 1978, upon returning to Fayetteville from New Orleans, Stanford found Wright, his lover, alongside his wife, Ginny, who had filed for divorce after she and Wright disentangled Stanford’s lies to each of them. Later, in his bedroom, having retrieved the .22-caliber pistol he kept in his office, Stanford shot himself three times in the heart, two months shy of his thirtieth birthday. In her essay “Death in the Cool Evening,” which shares the title of one of her husband’s poems, Ginny Stanford writes, “I heard the crack and just as sharp I heard Frank hollering, ‘Oh’— surprised…” Frank Stanford was buried beneath a stand of yellow pines in Subaico, Arkansas, wearing a kimono.

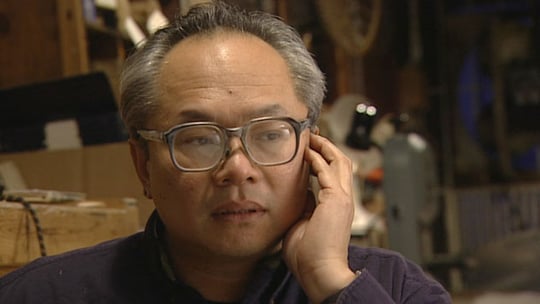

Jasper, a new monograph by photographer Matthew Genitempo, portrays contemporary life in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas and Missouri, serving as a visual companion to Stanford’s imagistic writing about hard lives in that hard place. The monograph grew out of Genitempo’s graduate work at the University of Hartford and was short-listed for the 2018 Paris Photo/Aperture Foundation First PhotoBook Prize.

Stanford’s poetry is full of eccentric, feral, goofy, and grotesque characterizations of the people the poet knew or imagined in his musings over life in the Ozarks. One of the most remarkable aspects of the poet’s work is that these portraits never feel exploitative or opportunistic. Distinguishing between documenting and taking advantage of one’s subjects is even more difficult for artists dealing in lens-based image making, but Genitempo’s formal portraits of subjects directly facing his lens are simultaneously dignified and mysterious. The black and white photographs in Jasper cast these figures in an oddly timeless light, bringing a dreamtime surreality to their isolated lives.

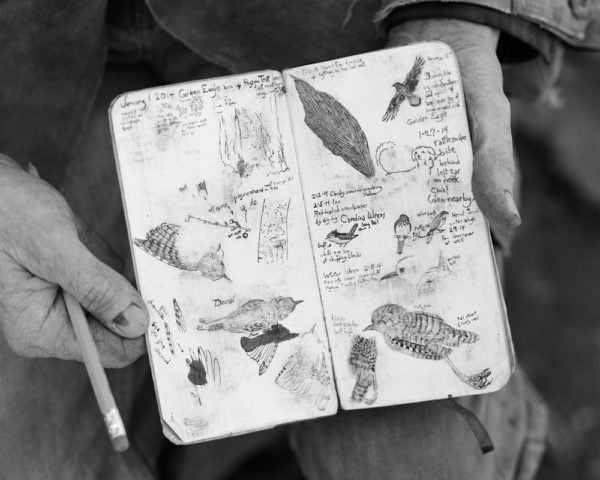

Genitempo also recognizes the storytelling potential in a black-and-white photograph of a person’s hands. Such photographs of men in Jasper show hairy forearms, dirty fingernails, and callouses. The men cradle their fingers around rifle butts, lovingly present pencil drawings of leaves and birds, and clean those dirty fingernails with the blades of pocket knives. These images feel both lovingly composed and gesturally dynamic, somehow formal and fleeting at once. It’s striking that Genitempo can register so many levels of visual and emotional impact with with the limited visual elements provided by a pair of hands in a close-up image, and even more impressive to see this level of quiet confidence on display in a photographer’s first monograph.

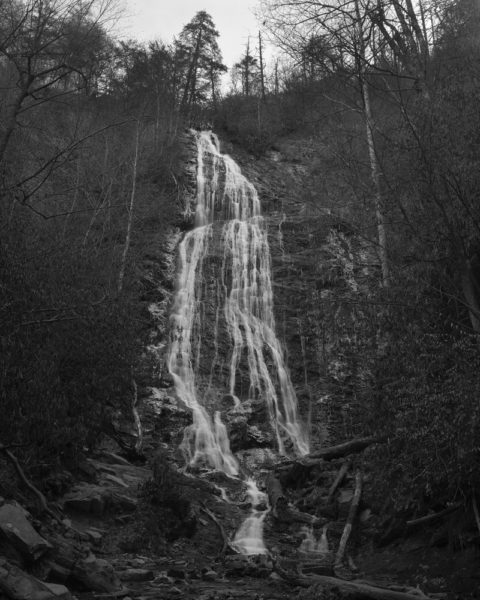

The Jasper Genitempo depicts isn’t the real Arkansas town—it’s the label that Genitempo uses to capture the state of mind that accompanies living deep in the Ozarks. As a poet, Stanford wrote a lot about those mountains and forests, but he was also employed as a land surveyor in the early 1970s. Stanford carefully measured this land with tripod and theodolite, but Genitempo always goes for mystery instead, shooting spooky photographs of animal shadows and ghostly clouds in low light conditions, creating images that imply as much as they reveal. There is a startling photo of the sparkling ivy-like rivulets of a waterfall descending down a rock face, and one of two sleepy dogs lying down beside the bleeding body of a brown buck, but even these daytime images seem full of mist and shadow. Genitempo might have included a section of gorgeous color photos of one of the most beautiful wild places in the country, but instead of showing us the Ozarks’ beautiful face, he aims his lens at the places in those mountains where there’s another kind of beauty that’s deeper, darker, and more poetic.