“Walker Evans: Depth of Field,” on view at the High Museum of Art through September 11, truly lives up to the show’s subtitle. Many people recognize Evans’s name or know his work, namely his FSA (Farm Security Administration) photos of the Great Depression, but his photo portfolio is much more diverse than that. For many decades, Evans worked as one of the nation’s top photojournalists, and his influence on the profession was significant. His works allowed viewers a peek into other worlds and other lives, and yet he, the photographer, remained a neutral party in order to document scenes as truthfully as possible. His philosophy of being “literate, authoritative, and transcendent” remain standards of photojournalism. This exhibition shows some of the best and well-known works by Evans, while also providing a robust overview of his full career.

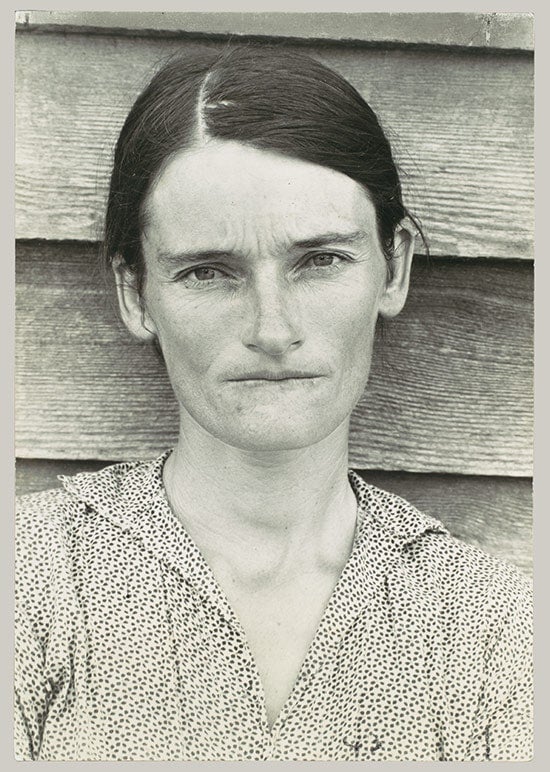

Some of the images in “Walker Evans: Depth of Field” are so iconic that most viewers already know them, even if they didn’t know they were by Evans. Alabama Cotton Tenant Farmer Wife (1936) is certainly one of those images. This photograph of a woman with a hardened visage standing in front of a slatted house became one of the most recognizable images of the entire Farm Security Administration project (which included such prominent photographers as Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks and Ben Shahn). The woman’s face is weathered, the details of her lips, eyes, and cheeks washed away by the effects of rural poverty. Evans brings a photographic perspective that is empathetic to this woman’s plight, and portrays her without judgment. Her ears stick out and her eyes cross a bit, but Evans doesn’t create a caricature. He arguably created the face of the Great Depression.

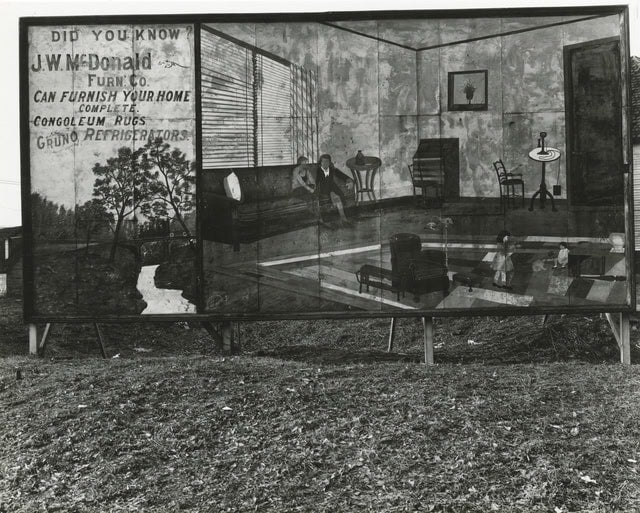

Evans reveals his deep knowledge of photographic technique in many of these images. Look closely at the images and you’ll understand how Evans carefully composes, crops, and frames his images to create strikingly narrative photographs. Oftentimes, the background and foreground seem to be in dialogue. In Street Scene, New Orleans (1936), for example, Evans frames a black man standing in front of a movie poster with a large image of a white woman’s face. The realistic, steely look of the black man contrasts with the idealized, glamorous white woman in the poster. In a single image, Evans captures the dichotomy of privilege, class, and race in the American South.

In the last few years of his life, Evans turned to Polaroid photography, and began dabbling in the world of color. At this time, the mid-70s, color photography was just gaining respect in the field. The grandiose, formal world of black-and-white silver gelatin photography dominated the fine-art and photojournalistic worlds. Color photos were for advertisements and hobbyist snapshots. Around this time, William Eggleston began to introduce deeply saturated color images of banal scenes into the fine art world. They showed color’s ability to transform the everyday into the exquisite. Evans, similarly, used color photography to capture mundane scenes (often close-ups of graphical elements) in new and exciting ways. Graffiti on Red Pole (1974) features a close up of a red wooden pole carved with names, a heart, and other scrawls.

What’s unique to Evans is that his color photos look like they could have been shot yesterday; you could imagine this red pole in Little Five Points today. Another image, Here (1974), is simply a close-up of the titular word painted on a green background. Evans strips the image of all context and meaning, reducing the photo to the barest elements of color and design. His return to a childlike photographic language at the end of his life is reminiscent of Matisse and his late-life color paper cutouts. Perhaps a simple and pure art vocabulary holds more appeal at the end of a long life as an artist.

This show, of course, has some of Walker’s greatest hits on display. With bodies of work spanning multiple commissions from popular magazines, this show exemplifies how Evans changed the face of photojournalism, and how his style still influences contemporary practitioners. The image selections for this exhibition are excellent, particularly those that resonate with Southern audiences (such as images shot in Atlanta). “Walker Evans: Depth of Field” reintroduces audiences to a photographer they didn’t know they knew.

“Walker Evans: Depth of Field” is co-organized by the High Museum of Art and the Josef Albers Museum Quadrat, Bottrop, in collaboration with the Vancouver Art Gallery. It is on view at the High through September 11.

Matthew Terrell writes, photographs, and creates videos in the fine city of Atlanta. His work can be found regularly on the Huffington Post, where he covers such subjects as the queer history of the South, drag culture, and gay men’s health issues.