Despite having her work exhibited in over 450 group exhibitions in more than 35 countries, Liliana Porter remains under-appreciated. Like so many artists of her gender, generation, and heritage, recognition is long overdue. But 2017 has been a banner year for this 76-year-old artist from Argentina: she was featured in the Venice Biennale, included in the Hammer Museum’s touring exhibition “Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985,” and has a substantive survey of her work on view through January 7 at the SCAD Museum of Art. While not a full career retrospective, “Other Situations” gathers more than 30 works made over 40-plus years, and the highly satisfying result hints at a more comprehensive retrospective’s potential impact.

The exhibition reveals shifts over the arc of Porter’s career, from conceptual reserve, through Surrealist games, to an embrace of the outright absurd. Throughout, her presentations adopt the veneer of austerity, achieved with perfunctory camerawork and bland compositions set against blank backgrounds. However, this aloofness is sharply countered by increasingly apparent doses of play and wry humor.

The exhibition begins with black-and-white photographs from 1973. In them, Porter adheres to many 1970s tenets. Like so many of her feminist peers, she works both sides of the camera, using herself as subject and her own body as a generative site. Simultaneously, like so many of her conceptual peers, she plays up the camera’s status as a dispassionate recording device to document ideas. Despite their relative coolness, these early works have a poetic beauty and delicate subtlety that many works from the ’70s lack. Untitled (Self-Portrait with Square) is a striking 1973 photo of Porter in which extraneous details have been minimized—the artist is dressed in a simple white tunic and stands against a blank white wall—focusing attention on a rectilinear shape (less regular and symmetrical than the square mentioned in the title suggests) that traverses her face. Part of the form is drawn directly onto her skin, and part of it has been drawn on the wall behind her, yet they visually connect in the flattened space of the photo. Similarly, Untitled (Triangle) from the same year presents three silver gelatin prints of the artist’s open palm, onto which lines that meet in an acute V-shape have been drawn. Those vectors are continued as graphite lines drawn directly onto the wall between the framed pieces, literally triangulating the images. The tension between real and pictorial space is a theme she would return to in many later works. These early conflations of bodies and geometric shapes break down distinctions between the organic and the mathematical, the spiritual and the rational.

Subtle poetics more explicitly turn into literary references in works from the late ’70s that are imbued with a sense of magical realism and Surrealism. For example, in The Magician (1977), Porter adapts a 1952 self-portrait by René Magritte in which he portrays a four-armed version of himself eating and drinking. In Porter’s photo, her hand reaches towards the open pages of a book in which the painting is reproduced, offering a fork full of food to Magritte’s mouth. By adding a fifth hand into the composition, she farcically one-ups the Surrealist master. But she also seems to be making a sly point about the nature of reproduction (it’s a photograph of a book in which a painting has been printed), as well as breaking the sanctity of the original painting’s picture plane. Exhibition curator Humberto Moro also ties this image to the influence of Argentine author Jorge Borges’s “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” a short story in which the notion of authorship is turned on its head.

A series of photographs from the early 2000s present ordinary objects in an unembellished, indistinct style to tackle the theme of coopted ideology. Mouse Pad Artwork (2004) presents a mouse pad printed with Che Guevara’s image; Martyr (2005) offers a modest piece of brie whose supermarket label reveals the Joan of Arc brand name; and Sugar Food/Christ (2006) captures a cellophane-wrapped sweet treat in the shape of a crucifix. With extreme economy, Porter shows us how capitalism commodifies everything from political ideology to religion, and turns the sacred into the ridiculously profane. Apparently, those with the conviction to die for their beliefs are fated to be memorialized as cheap office supplies and fattening food stuffs.

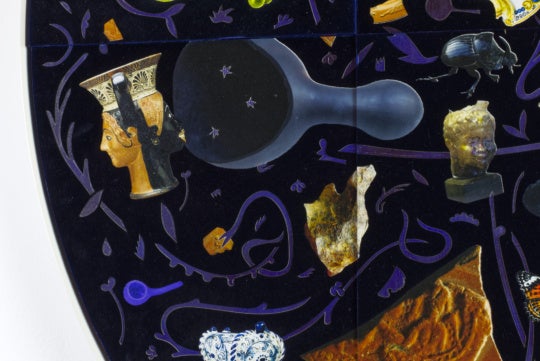

A decade later, Porter continued to use collectible versions of political, cultural, and religious heroes. In various photos, such as Memorabilia (2016), she mixes the above-mentioned icons in with such lionized figures as Elvis Presley, Eva Perón, George Washington, and Mao Zedong, creating gatherings that mash-up space, time, and belief systems. All subjects are represented with cheap tourist collectibles, like figurines, busts and printed mugs. As in the work from the previous decade, here Porter suggests that time and market forces deaden radicality, and that respect of individuals turns into blind idol worship.

More recently, the artist has turned to sculpture, enacting what she terms “theatrical vignettes” by placing tiny figures and objects onto shelves and pedestals or directly on the floor. These miniscule figures undertake acts of Sisyphean labor, out-scaled to their stature. Sometimes their tasks seem reparative, such as the woman sweeping up a proportionally enormous line of vacuum cleaner dust in Trabajo Forzado/Forced Labor (mujer barriendo/sweeping woman), 2004-17, and other times destructive, as in Man with a Pickaxe (2012), whose chopping action appears to have left welts in the gallery wall (a man with an axe is a recurring character in her work). Porter has spoken of her interest in the way that viewers can humanize and project interiority to inanimate objects. But identifying with these figures will only lead to or reinforce frustration. Unlike the eternal legacies of her icon/celebrity figures, these everyday people feel destined to never rise above their anonymity, or escape the trap of endless futility.

The video Actualidades/Breaking News (2016) is the culmination of Porter’s mix of unemotional detachment and absurdist humor. It is darkly nihilistic and, at times, very funny. Ceramic figurines, toys, books, and other props are set against plain backgrounds and animated or manipulated with child-like, low-tech effects. The piece strings together unrelated, short vignettes, each introduced by dual Spanish and English titles. Some titles are loosely related to categories of media news coverage, such as Policiales/Crime Coverage, while others evoke concerns of the state, delivered in a controlling institutional voice, such as ¡Cuide Su Salude!/Protect Your Health! In each, an insignificant scenario plays out as a lame stand-in for a greater societal force or ill. Violencia Doméstica/Domestic Violence,” for example, delivers images of dismembered doll parts, while Estado Del Tiempo/Weather Forecast shows a motley assortment of figures pummeled by a storm, crudely produced by off-camera fans and clumsy splashes of water. The entire video is accompanied by a musical score that supports the promise of action and melodrama. The urgency of Actualidades/Breaking News’s title exposes media sensationalism, while serving as a foil for the content delivered; far from timely or informative, these scenes are ridiculously banal and useless.

It feels significant that Porter made this video in the year that Trump was elected President. Its use of insignificant props in place of people, and its deliberate reduction of the important to the inconsequential feel just right for our “fake news” era in which manipulated information misinforms and distracts. In Porter’s universe, politics and religion are reduced to stereotypes, and the extraordinarily destructive is normalized. These conditions feel all too familiar.

“Liliana Porter: Other Situations” runs at the Savannah College of Art and Design Museum of Art through January 7, 2018.

Lauren Ross is a curator and writer based in Richmond, Virginia, and the founder of RVA Critical Art Writing Program.