Art spaces in Birmingham, Alabama are opening one by one like so many lights blinking on as the sun sets. While the pandemic isn’t behind us yet, there is sense that its twilight is near and that we are entering a new phase. One of these slowly reopening spaces is Space One Eleven. Last week I had the pleasure of visiting their current exhibition, JUSTINJUST, which is presented in collaboration with the Jefferson County Memorial Project. 1

The exhibition reflects on issues relevant to the events of the past year—it is a well-timed inhale after so much collective breath-holding. While the timing is fitting, the exhibition was in the works long before 2020, as the planning for this project began three years ago. Throughout its thirty-odd years of operation Space One Eleven has curated most of its exhibitions to promote social justice; however, they have done so on tippy-toes, navigating a sometimes hostile local community who tend to perceive the gallery programming as being too progressive or liberal. Now, however the leaders of Space One Eleven now cite a warmer welcome for exhibitions that center race, social justice and other so-called “progressive” perspectives. It is hard to tell whether that is a sign of transformation or of performativity in this community. The context around JUSTINJUST deserves explanation because of its importance in interpreting the exhibition, which comprises contemporary work from artists predominantly located in the southeastern United States, with an emphasis on Alabama artists.

JUSTINJUST is an exhibition of works created by artists who are responding to our nation’s history of racial injustice. The exhibition is partially viewable from the sidewalk, where passers-by can see work on display in the windows. The most prominent of these is From My Eyes—Black Death by Joel Fuller, a digital illustration that has been printed at the scale of a storefront window. At this scale, dead Black bodies appear larger than life and cannot simply go unnoticed. Accompanying this prominent image are a series of QR codes that correspond to details in the composition, each of them directing viewers to related information online. Through the adjacent windows pedestrians can also see a red gown, a work of fashion-as-memorial titled Infringement of the Black Queen by fashion artist Kenya Buchanan. Compared to the larger-than-life images of Fuller’s image, seeing a garment at human scale recalls the embodied humanity of a prominent victim of police violence against Black people: Breonna Taylor (whose image is displayed next to the dress). “I want you to see past and present injustices” against Black women, Buchanan writes. Behind the gown is another textile work, a quilt titled Strange Fruit: A Century of Lynching and Murder 1865–1965 by April (Anue) Shipp that memorializes victims of lynching. The work recalls other lynching memorial projects such as the Lynch Quilt Project (recently presented in Alabama at University of Alabama at Birmingham) and the Peace and Justice Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama. Strange Fruit… is made of black satin with gold thread, a regal presentation that uplifts the victims it names.

Tying two spaces together, the adjacent gallery also features a quilt by artist Amber Quinn, who inherited the heirloom from her family. Next to Quinn’s family quilt is a photograph, All in a Day’s Work pt 1, and a presentation of ceramic tiles, Reunion, created by Quinn as a translation of her family’s quilting tradition. As Quinn explains, the incomplete grid of textured ceramic squares are “an acknowledgement that even though there is a lot of missing information, and we can never truly know the enslaved person’s experience, the overall pieces still manage to hold one another and support each other.”

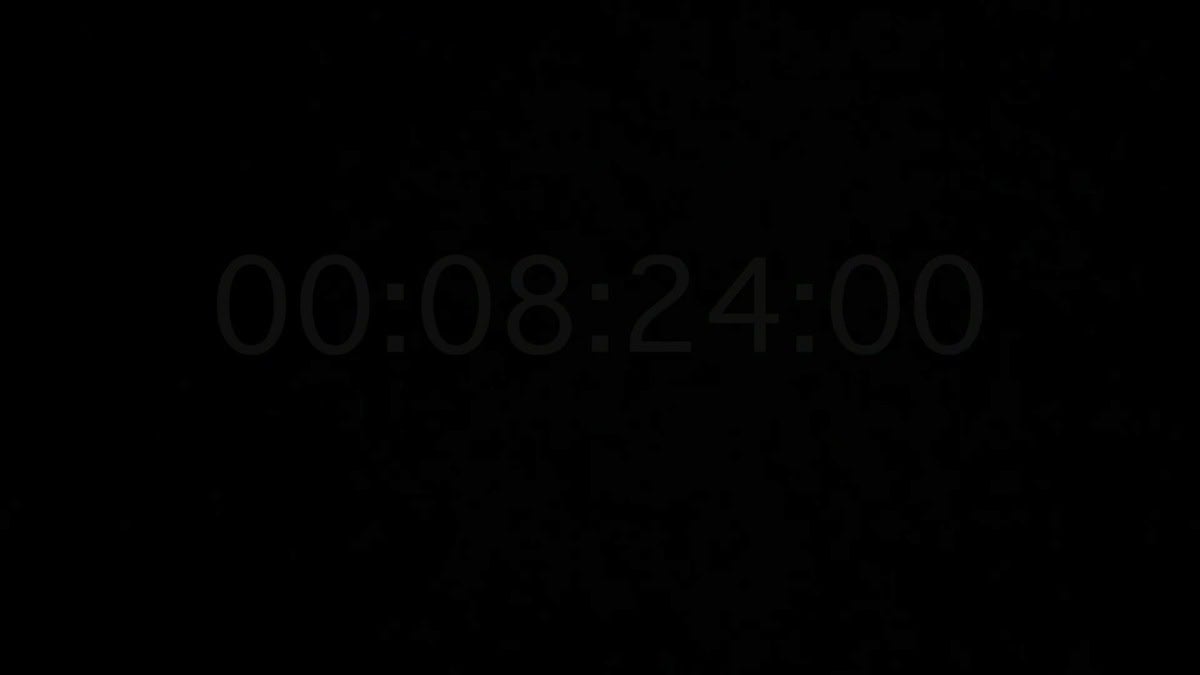

The rest of the exhibition in this second, larger gallery operates in a similar fashion. Together the artworks present an incomplete but robust picture of racial injustices: economic and healthcare inequality highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, injustice against immigrants, police brutality, failing courts and prisons, and more. Anchoring this room is a large video work on the back wall, 8 minutes 46 seconds by Paul Stephen Benjamin, which is composed of a digital clock that ticks the minutes and seconds of the duration stated in the title. The format of sans-serif numerals on a dark background recalls On Kawara’s date paintings, but Benjamin’s video is subtler, projected with low contrast onto a black-painted wall in a bright room. The viewer must really look—must choose to see the time passing—in order to perceive it. The duration that Benjamin’s video memorializes is the length of time that Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin’s knee was pressed onto George Floyd’s neck on May 25, 2020.

JUSTINJUST is more than a smart presentation of stellar and timely artworks. It is also a platform for artists whose work our community needs to see and, hopefully, a springboard for deeper and sustained engagement with their work.

JUSTINJUST is on view at Space One Eleven thru May 28, 2021.

1 As a white writer, it is important that I acknowledge my racial identity, which I share with the leaders of Space One Eleven. Neither those gallery directors nor I are (or should be) at the center of this writing, but I include this endnote to emphasize the importance of transparency for art writers, curators, and directors, especially when we present or discuss stories that are not our own.