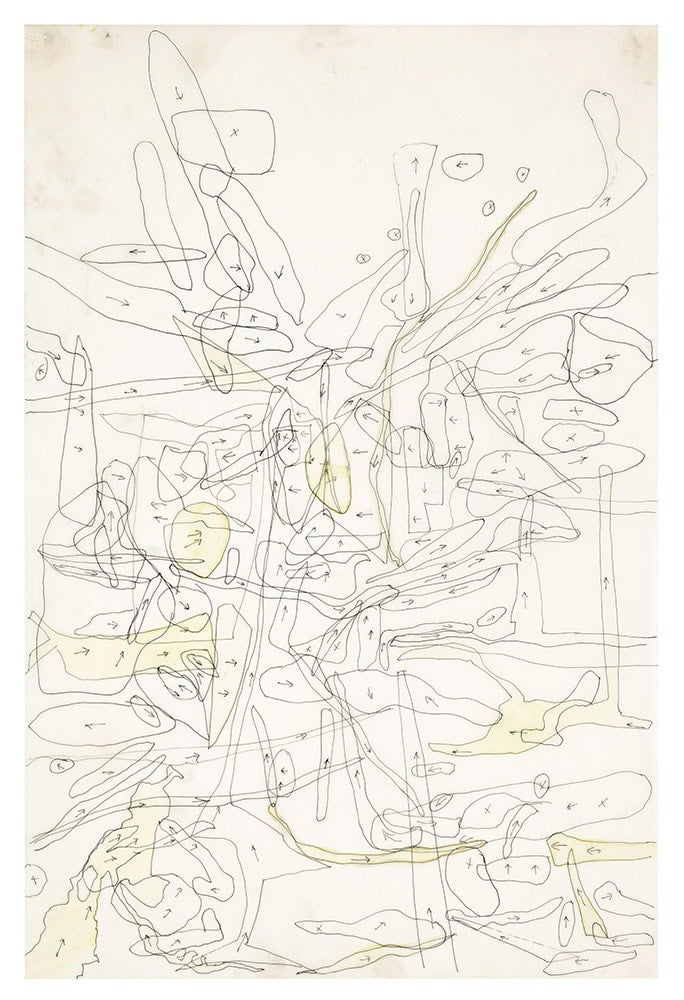

Minuscule pictograms—pairs of upward-pointing arrows, irregular T-shaped forms, shield-like circles—are arranged along an X-Y axis on a small mylar sheet bearing the handwritten inscription timeline analysis of character behavior. On other, slightly larger mylar sheets, these “characters” are indexed in terms of “conflict location” and “character migration,” and overlapping fields marked with arrows suggest quasi-cartographic models of motion. Though relatively rudimentary, these visual elements from works on paper from 1996 and 1997 contain the germinating forces that have animated the paintings of Ethiopian-born, New York-based artist Julie Mehretu for over twenty years. Nestled in a side room located roughly halfway through Mehretu’s career survey at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, these early notes and sketches provide more than a vague preview of the enormous, meticulously layered canvases that would follow in their wake: they give an invaluable glimpse into the logic that has consistently structured Mehretu’s ideas about making paintings over the course of her career.

Julie Mehretu, Migration Direction Map, 1996; ink on mylar, 18 by 12 inches, private collection. © Julie Mehretu, photograph by Cathy Carver.

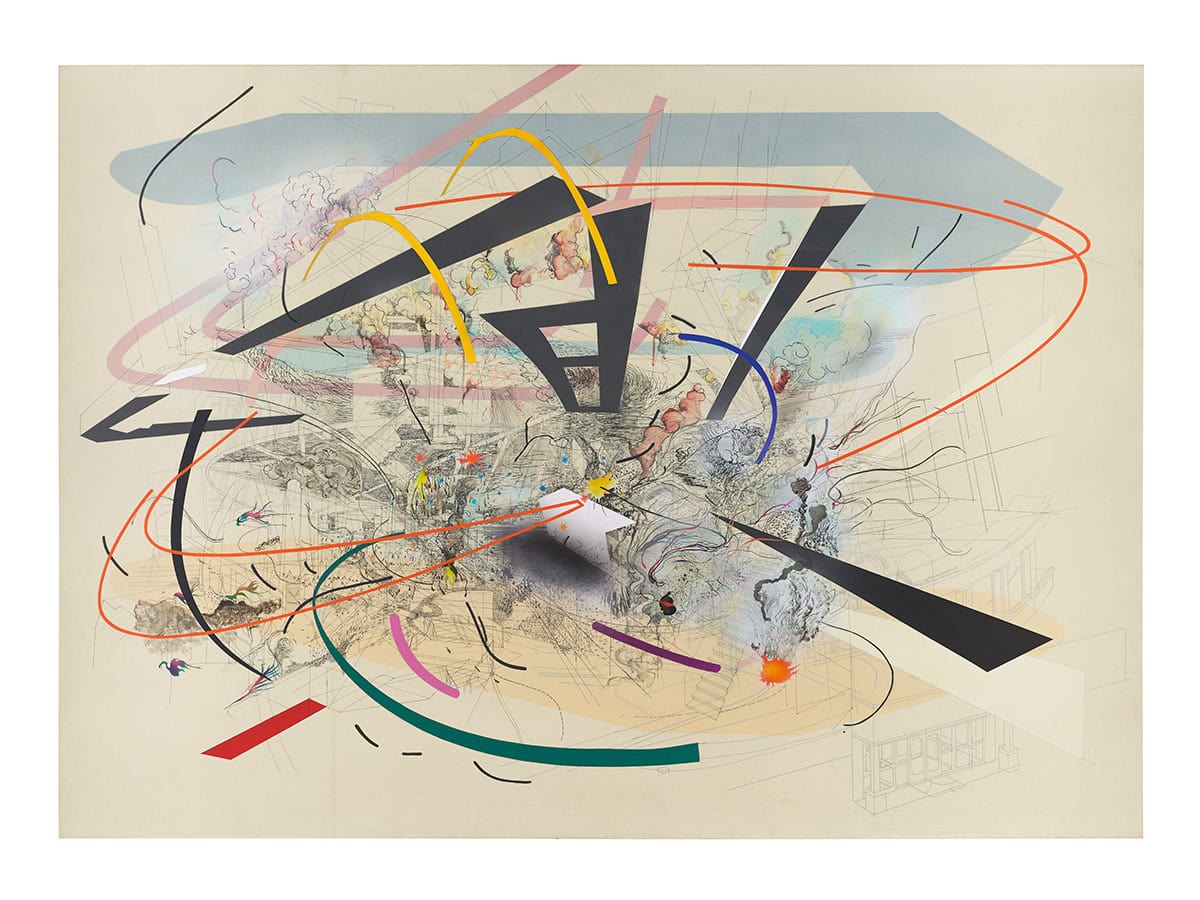

In 2002, a year after completing a fruitful year-long residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, Mehretu told the magazine Flash Art, “The characters in my maps plotted, journeyed, evolved, and built civilizations… As I continued to work, I needed a context for the marks, the characters. By combining many types of architectural plans and drawings, I tried to create a metaphoric, tectonic view of structural history.” In the painting Babel Unleashed (2001), characters populate overlaid architectural renderings of stairs and buildings that appear to collapse and ascend over each other, unbound from a single focal point or unified perspective. The fields of motion from previous sketches have condensed into curving, hard-lined planes of opaque color in forms reminiscent of Kandinsky and the Constructivists. Although the increasing visual complexity of Mehretu’s paintings resists a simple or linear explanation, the recurring central tension in her work—between constructed spatial signifiers of history and hierarchy and gestural markers of human idiosyncrasy—is already clearly defined in Babel Unleashed.

Reflective of her firm artistic grounding in drawing, Mehretu’s approaches to mark-making during this period convey the dynamism and action of comic books and manga, with paintings such as Untitled 2 (2001) featuring graphic explosions and bursts of color resembling the flame decals sometimes seen on hot rods and motorcycles. The painter’s characters are more loosely rendered than before, and dense clusters of calligraphic marks appear as clouds of smoke, rising from architectural fragments to an unsettling effect, recalling images of 9/11 and other scenes of catastrophic destruction.

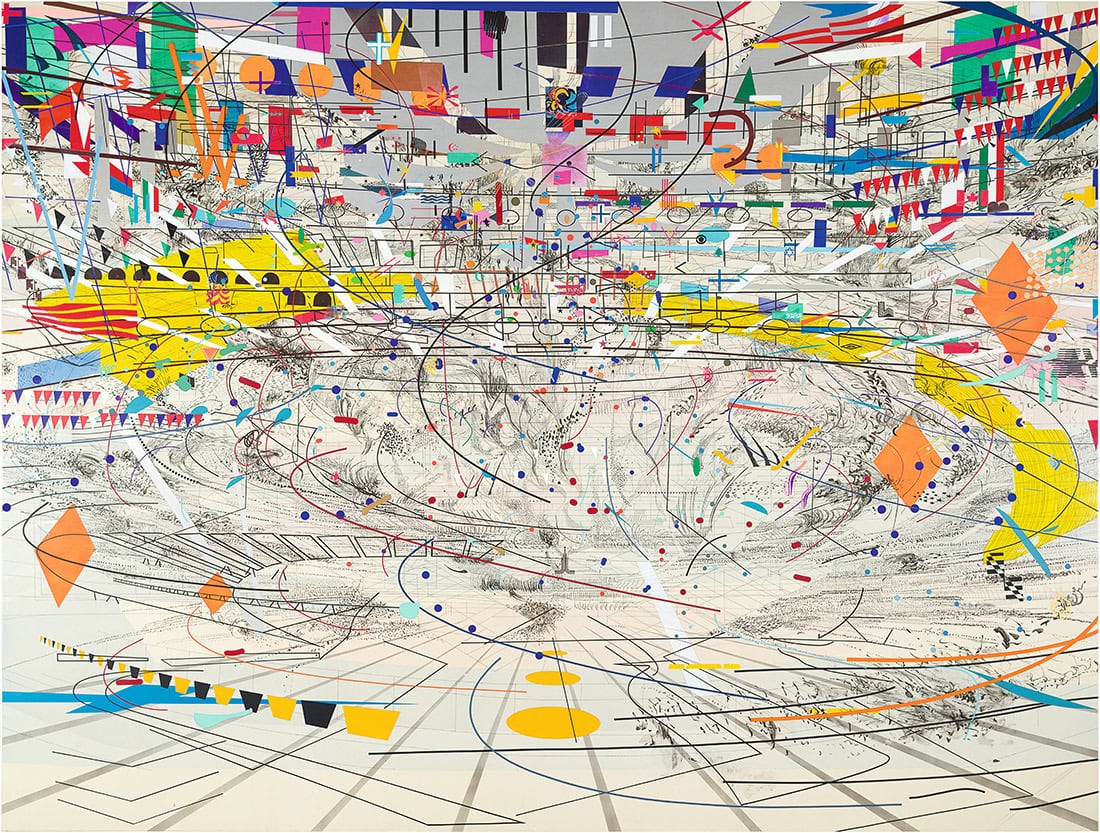

In the following years, under the atmosphere of the global War on Terror and the return of the Olympics to Athens, Greece, in 2004, Mehretu began contemplating the stadium and amphitheater as “perfect metaphoric constructed spaces”—designed for the democratic organization of crowds but also containing latent “undercurrents of complete chaos, violence, and disorder.” In Stadia II (2004), a panoply of colorful geometric shapes and abstract banners cascade above and throughout the centrifugal currents of a coliseum-like structure. Character-marks are arranged into battalion-like groups in stadium stands, and the five-sided star associated with American military insignia appears multiple times across the canvas. Despite its visual exuberance and sense of motion, the bloated pageantry of global capitalism and American empire imbues Stadia II with an almost dystopian quality, its central void opening like the eye of a storm.

In another painting from 2004, The Seven Acts of Mercy, multiple stadia structures overlap and expand over each other across a wide, horizontal canvas. Layered over these, swaths of undulating black ink appear to travel across the expanse, outlining vast trajectories of consciousness and action. Tempered by a monochromatic palette and enlarged both physically and affectively by its increased scale, The Seven Acts of Mercy shows a leap in the ambition and rigor of Mehretu’s painterly execution, signaling a shift to larger canvases and even more sophisticated compositions.

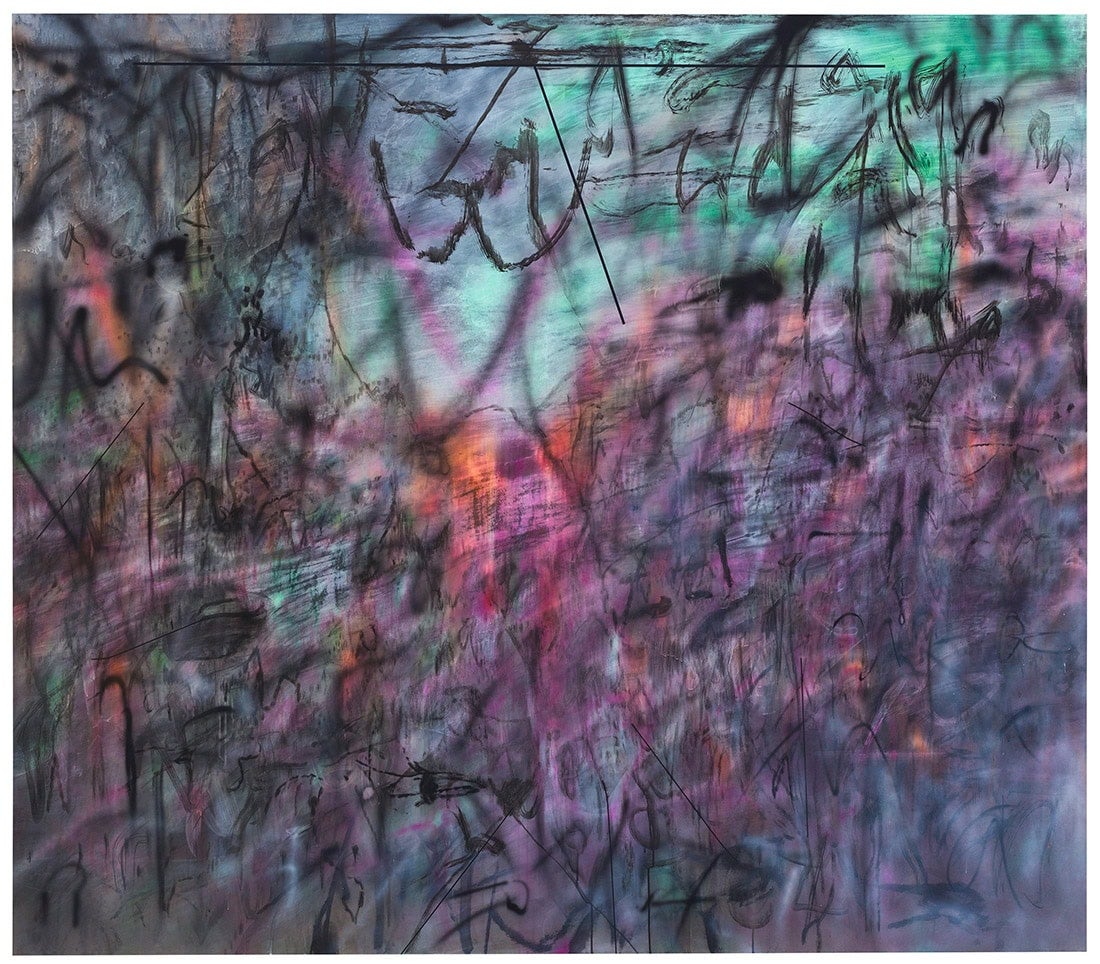

Because she worked on it daily during the seventeen days of the Egyptian Revolution in January and February 2011, the artist has called Invisible Line (collective) her “revolution painting.” In addition to this political and historical association, however, it also represents transformative developments for Mehretu as a painter. Instead of focusing on the structure of a particular form, such as stairs or stadia, Invisible Line contains citations from the many contradictory architectural styles of New York City: there are façades of buildings gridded with windows, archways and arcades. Throughout the painting Mehretu uses densely ordered groups of marks to create overlapping fields of depth, each glyph the flickering shadow of a soul within the overcrowded metropolis. Similar to the heavy, dark smudges that dominate Black City (2007), broad marks reminiscent of aged graffiti create areas of erasure across the cityscape, psychogeographic desire paths worn down by collective use over time.

Layering architecture upon architecture, entropy upon order, gesture upon geometry, Invisible Line offers a comprehensive image of the city, compressing thousands of points of information upon each other like a zipped file. However Mehretu’s mark-making has changed or developed since the beginning of her career, its function as evidence of the artist’s hand—and, therefore, of individual idiosyncrasy—remains constant. Fifteen years after she mapped out a series of pictograms, Mehretu’s characters no longer looked the same, having evolved into a vocabulary of dense staccato marks. They also no longer represented imaginary or fictional civilizations but attempted to capture a sense of the role of individuals within the archeological unfolding of history: the protestors of the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street demonstrators, Tank Man in Tiananmen Square.

Originally created for Documenta 13 in Kassel, Germany, Mehretu’s Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) (2012) pursues these world-historical impulses on an immersive, sublime scale. The painting takes its name from an Arabic word meaning “the complex” or “collective,” a title shared with an Egyptian government building on Cairo’s Tahrir Square that was occupied by millions of protestors calling for the removal of President Hosni Mubarak in 2011. Across four monumental vertical canvases, Mogamma overlays and inverts architectural details of buildings on Tahrir Square—a focal point of the 2011 revolution—seen from various perspectives. Dense smudges and congregations of marks unfurl and dissipate in swarms of activity alongside regimented arrangements of blocks and circles that suggest screen-printing or digital technology. As in Invisible Line, which rehearses much of the visual language for Mogamma, lines of pastel and neon color pierce the largely black and white painting. Geometric shapes and planes also reappear in Mogamma, but here they are less opaque, revealing more of the underlying structure. Viewing all four parts of the painting together, it becomes obvious how they are connected, visually continuous. Unfocus your eyes just right and the clusters of marks almost appear to move across the canvases like a murmuration of starlings, or the backward-looking angel surveying the ruins of history.

In the paintings that followed Mogamma, such as Being Higher I and Being Higher II (both 2013), Mehretu explored using her hands and—in the tradition pioneered by David Hammons—her body as a mark-making tool. By the time she began working on the Conjured Parts series (2015 – 2017), photographs had replaced architectural drawings as the primary visual scaffolding for her works. The title of each painting in the series combines the names of body parts and cities where violence or political strife have occurred. For example, Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson (2016) allegedly began with images of police in Ferguson, Missouri, following the police shooting of Michael Brown in 2015. The painting shows no visual evidence of this image now: layers of color are burnished to reveal further depths and graffiti-like smudges. Similarly, the composition of the fluorescent orange Hineni (E. 3:4) (2018) is supposedly derived from photographs of California wildfires and the burning of Rohingya homes as part of a campaign of ethnic cleansing in Myanmar. Although the relative opacity of many of these more recent paintings remains consistent with Mehretu’s long-held ideas—as social order erodes, so do the spatial structures undergirding her paintings—they lack the distinctive balance of technical delicacy and visual heft that makes her previous works so moving and compelling.

Before leaving my second visit to the exhibition earlier this month, I returned to sit on the bench facing Mogamma. After a few moments looking at the painting, I realized someone else was standing nearby, looking with me at the same time. I was struck by the impresion that we—two strangers standing on the second floor of an International Style-building that would be at home in a Mehretu painting, each brought to that precise place and moment by the invisible forces of coincidence and personal history—were characters ourselves. Afterwards I wound my way down the museum’s multi-level spiral walkway, imagining myself as one of countless minuscule marks moving through time and space.

Co-organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and the Whitney Museum of American Art, Julie Mehretu is on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through January 31, 2021.