Processing feelings of grief is vital in order to acknowledge the pain a body can go through in loss: loss of health, loss of routine, loss of who a person once was, and the role they played in one’s life. In June, I spent tireless moments in the Intensive Care Unit of a neighboring hospital with my father who suffered from a crippling infection. I became a medical dictionary, understanding how to read the beeps of a machine, how extubation affects the body, and how delirium impacts one’s understanding of time and reality. As the days accumulated, I accumulated adhesive identity badges in a range of colors. Now, I bend to time for healing a body that has gone through so much.

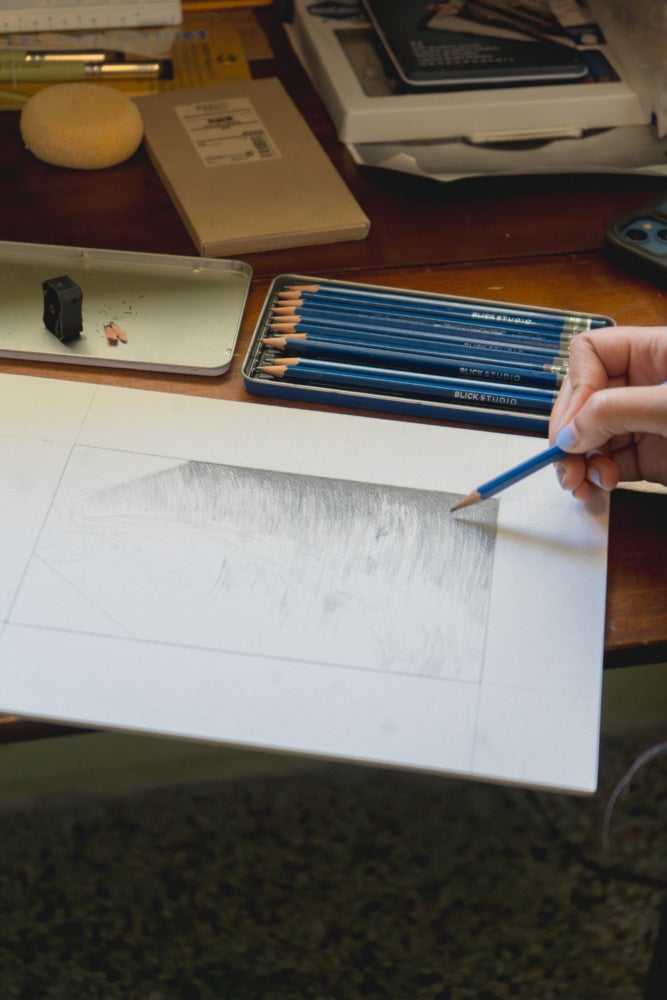

Smita Sen’s interdisciplinary practice beckons viewers to witness her own grief because studying something as concrete as the body can help one understand the not so concrete waves of emotion a being goes through. In visiting Smita’s home studio in the Kendall neighborhood of Miami, we spoke about emotions following the closure of her recent solo exhibition, new works exploring the heart, and resting while grieving.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Isabella Marie Garcia: In your most recent exhibition, Embodied at Museum of Contemporary Art, North Miami, you consider the body’s physical capacity for grief and how both the human body and abiotic objects, such as fossils and chemical signatures, preserve memories of life after death. In the wake of the exhibition’s closure, I think about how to process response and public reaction, especially as performance was a large part of the show. How do you feel about how the work was showcased and how the public received it?

Smita Sen: The show was like a mini retrospective, where it was works from 2015 all the way up until now. It was really meaningful to see audiences, to see visitors of every kind [including] art, non-art background, connect with the work. What was really special was seeing everyone just connect with what I was going through on a personal level, but also connect to the artistic methodologies that I’m using and the visual language that evolves with time. That was really reaffirming, and also was a closing of a chapter and gave me permission to dive into the next phase of art making.

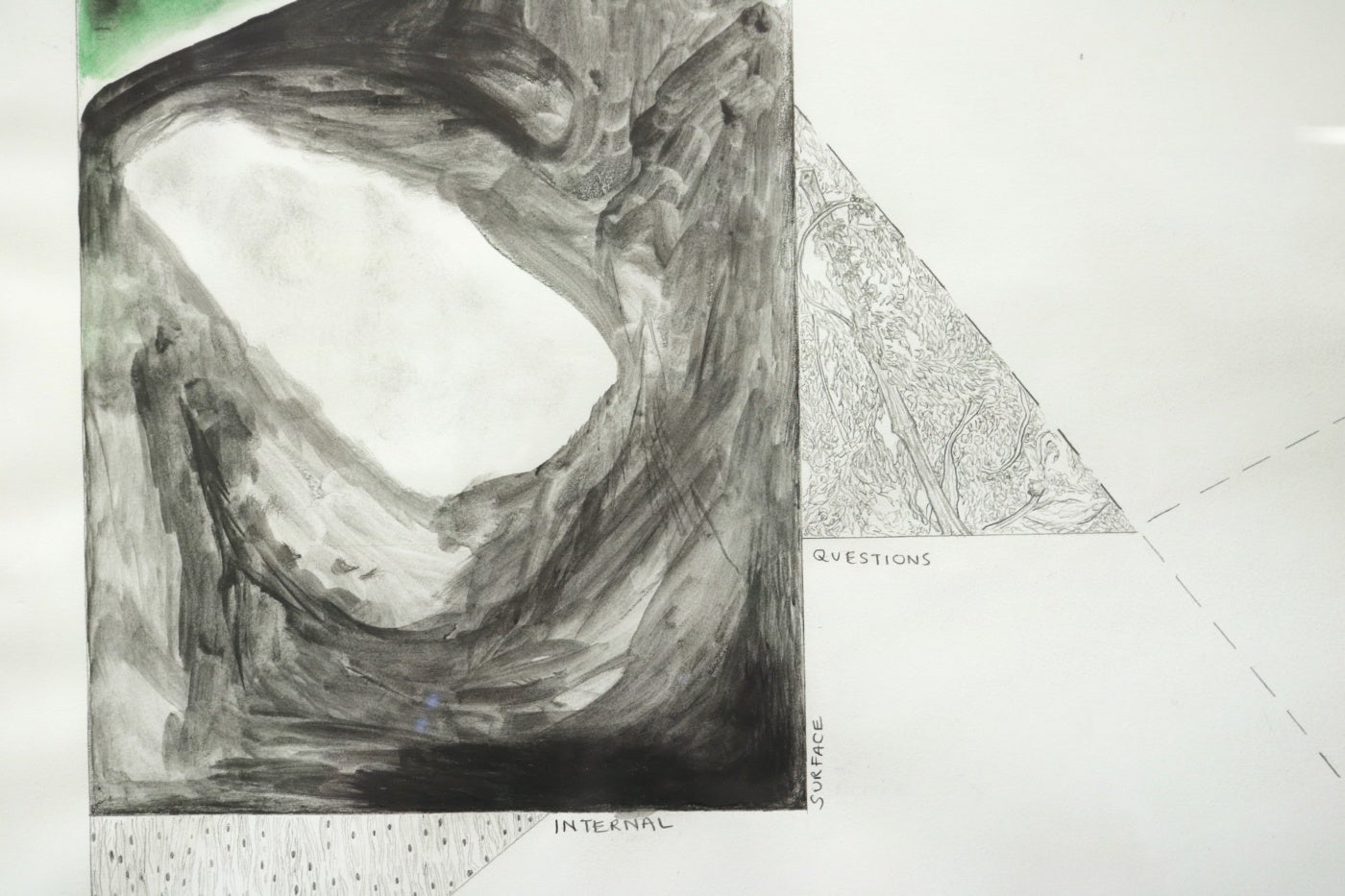

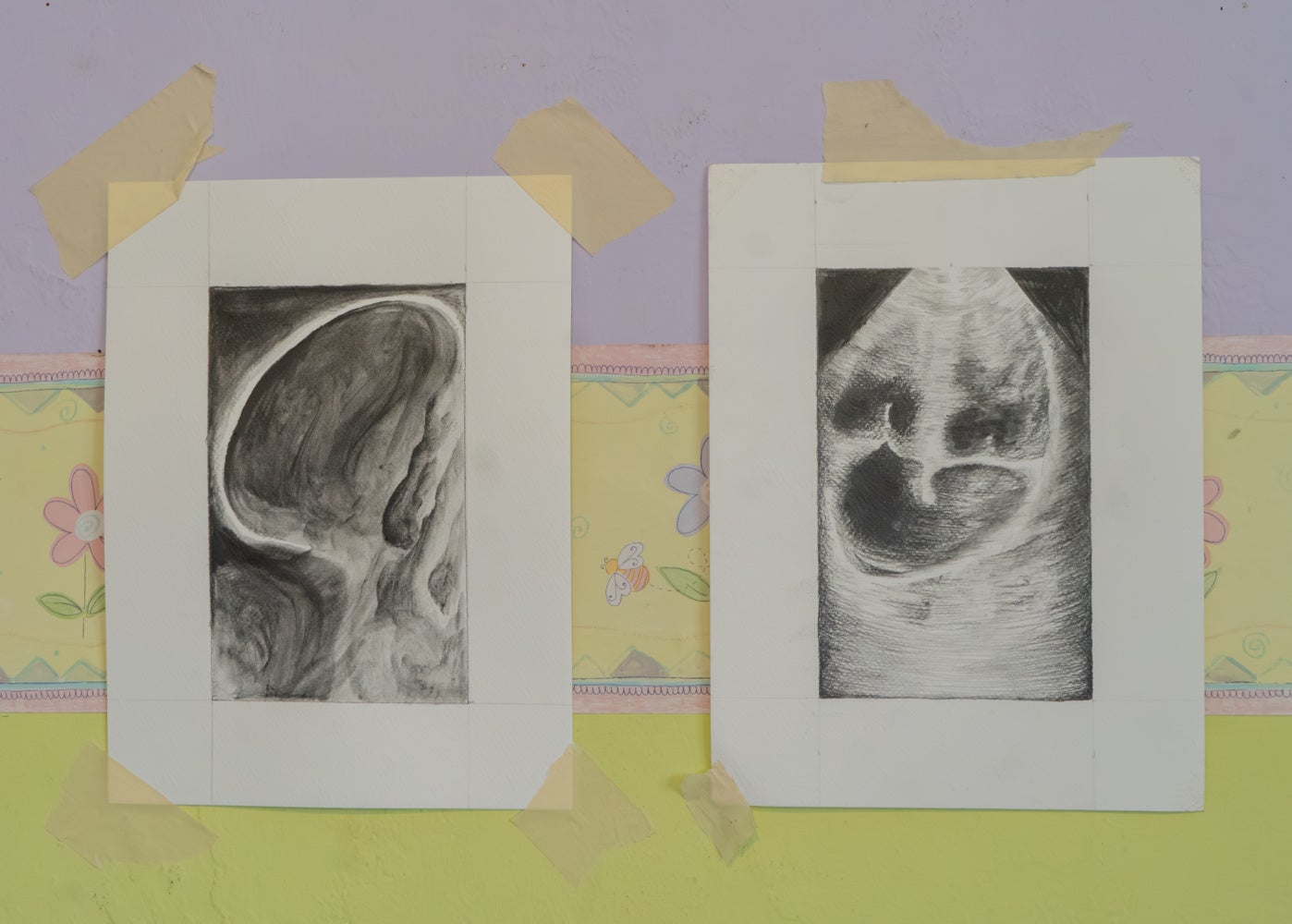

I’m making these new pieces about the heart and about hereditary illness, but also about the heart as both a medical and a spiritual phenomenon. There’s this understanding of the human heart as an organ and as this site of electrical conductivity that can be a place for recognizing the impact of interpersonal relationships at the end of life. Then we also have this muscle, and it’s self contracting. It is super fascinating because it does not need to receive impulses or information from the brain in order to function.

The interesting thing is that in Hindu, both in spirituality and also in religious texts, there’s this really interesting emphasis on the heart as the bridge between worlds. The heart has this identity as being the heart chakra and this energy center that can connect the physical and the spiritual. In order to bring somebody back to life, you defibrillate the heart. You don’t introduce electrical pulses anywhere else, right? You defibrillate the heart. Therefore, you can summon the spirit back into the body.

The new work is all about the heart. It’s about hereditary illness. It’s about what we inherit from our loved ones. It’s also about the complexities of medical and spiritual history and the way these things intertwine. I’m looking at a lot of archival texts, both Hindu and mid-eighteenth century British and Indian colonial medical documents, as well as contemporary Western medical documents.

IMG: Wow, that’s super fascinating! In dealing with my father’s health situation right now, I’m learning more and more about how the body is a game of balance. How do you find these resources that you pull from in your work?

SS: I work with Narrative Medicine theory, which is Dr. Rita Charon’s theory, but also the practice of understanding the patient narrative and narratives introduced by imaging and physical diagnosis. How do you bring all these things together and think about the doctor as someone who can unite different narratives together and make sense of them alongside the patient? I’m going to a lot of different, old school academic resources, like books and pulling them apart, seeing what I can find. Image research is harder and I’m a JSTOR hound, so I’ll go into academic journals and just try to find as much as I can. Whenever I can get in touch with somebody who has access to an archive, they are pretty open about sharing materials, but it’s just about getting in touch with the right group of folks.

The new work is all about the heart. It’s about hereditary illness. It’s about what we inherit from our loved ones.

IMG: The series, The Geology of Longing, is a love letter in a way to your father’s career as a geologist. In visiting the sites where your father worked after his passing, what was that process like of retracing and then formulating these films about pilgrimage in the wake of loss? Are there any stories, highlights, and challenges you’d like to share on that process?

SS: It’s quite special, because a lot of these sites I haven’t been to, but I’d heard [about] my entire life. It was such a privilege to be able to go back to other locations that I hadn’t been able to visit at all since my dad’s passing. I was able to get a grant, and when we went to go film in February, it was nine years to the day that my dad took me on a site visit. It was incredible to see the photographs of him and I together on that day, in 2014, and then in 2023 to be shooting the film.

To see how a place evolves, how you evolve, and how these two things become mirrors of each other, and where we view meaning. All of these different films are pilgrimages to these sites. If I can’t find my father at a grave site, because in a lot of Hindu practices, we don’t do grave sites. We cremate the body, and then we scatter the ashes, or we hold on to the pieces of the ashes. There’s this strong sense of belonging where my father’s wandering soul, nomadic soul, would be in these other places where his heart and mind really belonged. At each location, I would read his writing. I would read his academic writing. I would read the writing of his friends and colleagues. For the first film, I interviewed my godfather, who was his colleague, and it was special to talk to him about science and hear the affection with which they would speak about these places. Geologists are funny. They’re very tender.

IMG: My understanding is that you work between Miami and New York, correct? That immediately made me think both about how the environment plays a factor into art-making, but also how it is received by viewers. How do both cities contribute to your work and how is the performance work you’ve executed received in those two communities?

SS: Miami, for its performance community, is still much more dominated by music and dance than it is by experimental performance. The types of music and dance are also very contained where it’s like, either you’re working with like western classical, Western jazz, or you’re working with like Latin American and Latin jazz, right? It’s beautiful and you can really do a lot with those forms alone.

In New York City, you have those and everything else, right? You have a lot more South Asian classical, South Asian contemporary, South Asian experimental. You also have East Asian, Southeast Asian. You have African, West African and South African and East African. You have so much to pull from, and there’s also so many more conversations of exchange. It makes for a really lush landscape of performance, both in terms of traditional and experimental. It makes it really possible to have a lot more feedback, but also a lot more audiences and a lot more audience engagement.

It’s been a necessity for me to have this split presence between Miami and New York City because it would be very hard to grow my performance practice without the support of both. Miami is investing very heavily into those of us who are here to grow vertically, whereas, like in New York, there’s a lot of support to grow laterally and to connect with a lot more people, with whoever is around. I need both, but I think that Miami has given me a lot of platforms to showcase and to present and share what I’m working on and the ways I’m working on it.