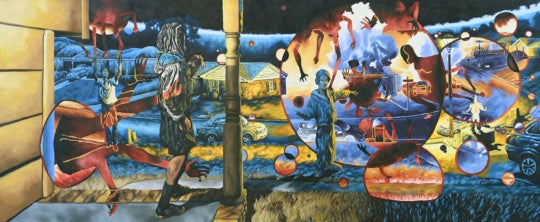

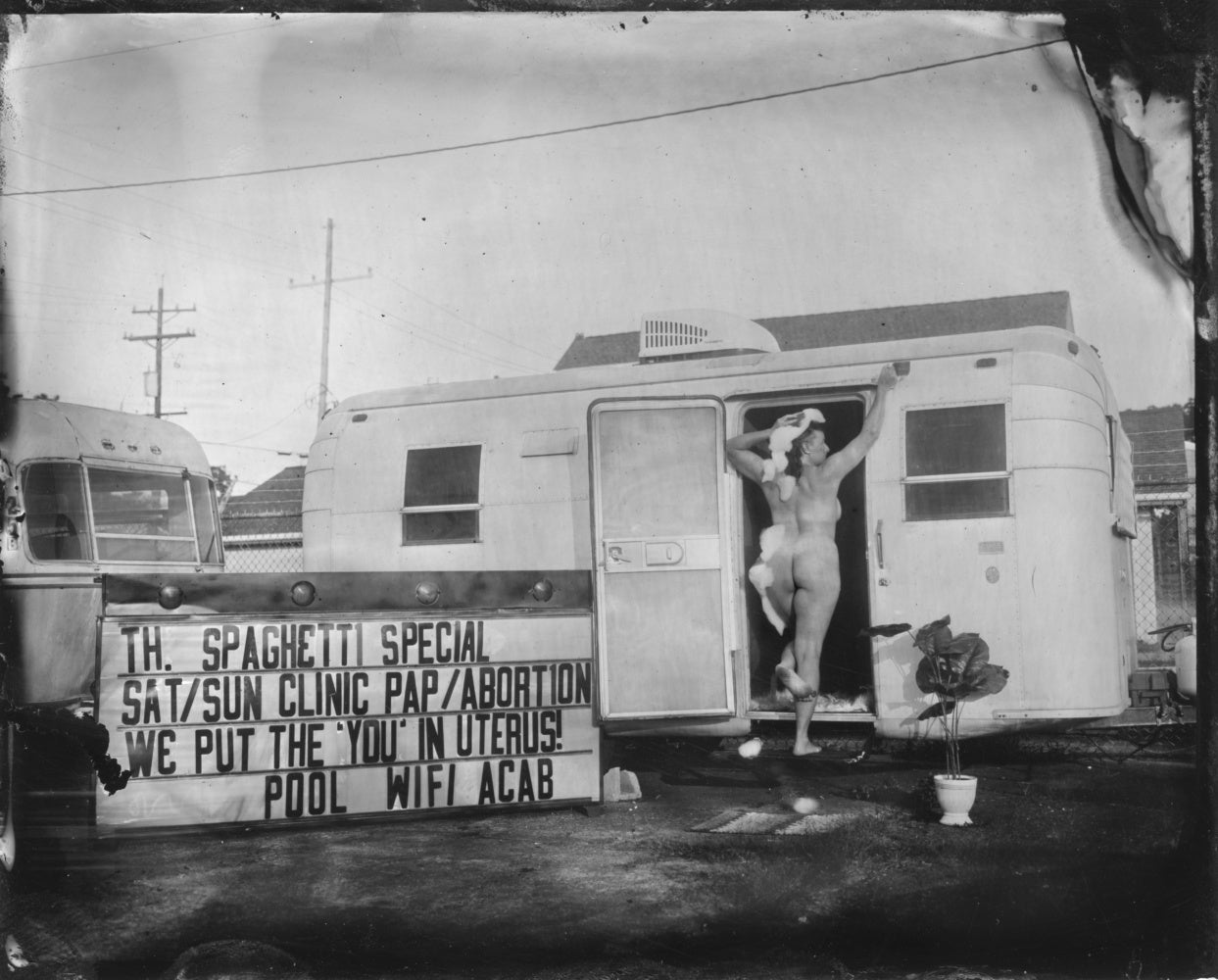

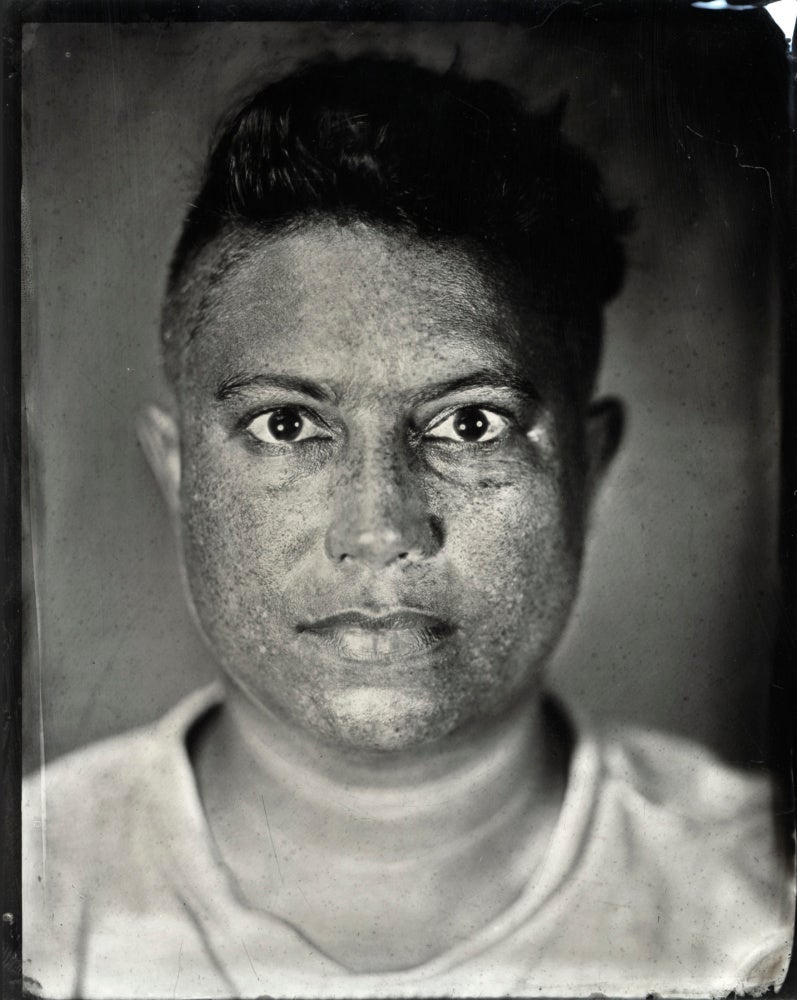

Meg Turner utilizes antiquated photographic practices, such as tintype and photogravure prints, to create an archive of her life in her adopted home of New Orleans. Identifying primarily as a printmaker, the body of work she has produced over the past fifteen years is populated by tableau vivants of teachers, sex workers, punks, community organizers, lovers, and friends, which establish a telling self-portrait of the artist via the subjects she is compelled to collaborate with in the picture-making process, as well as an archive of an often transient and nomadic community that has been subject to historic erasure and neglect. These works often explore anarchist themes; her subjects’ sexualities, genders, and nude bodies; health care [i.e. access to abortion, PPE, gun/birth-control, and life-saving resources via harm reduction]; and anticapitalism via built utopias and the natural world. Turner was a founder of the New Orleans Community Darkroom and Printshop, which has provided free and low-cost artmaking classes to the New Orleans community since 2009; she has taught printmaking at Tulane University since 2021 and more recently, a photogravure workshop at the University of New Orleans this past fall. An exhibition of the artist’s work at Gryder Gallery in December, in which Turner will show both new and familiar works, and the release of a second volume of the artist’s photobook WET, which will be published by Women’s Studio Workshop in the spring. Our conversation took place in the studio of Josephine Sacabo, a New Orleans-based photographer whom Turner works as a studio assistant. This interview has been edited and condensed for brevity and to clarify names, terms, and locations referred to within the text.

Lauren Stroh: Can you tell me a little bit about what prompted you to come to New Orleans [when] you moved here in 2009? Were you experimenting with [printmaking] before you arrived?

Meg Turner: I studied printmaking in Rhode Island at RISD. I had a different practice in that it was all architecture based. But for me, there’s kind of a through line of places that I loved and that grounded me. And in my professional practice, I started the community printshop in Providence when I was in college—or rather, a larger organization started one with a group of volunteers. I was really interested in how to teach these practices and have access to them outside of being in college. And I found that I really enjoyed the teaching process and having access to that communal space because, although right now I’m in a private studio in Arabi, generally this type of equipment is very expensive. So then you work collaboratively—and that’s always something I’ve loved about printmaking in general and its tie to radical movements around protest: having that kind of access to how you make art, how you disseminate information, how you make graphics. That is all tied into why I love printmaking and why I think of myself more as a printmaker than a photographer. It’s much more of a collaborative thing. I moved here and I took a job inside Louisiana Artworks, which was a wildly mismanaged organization. It closed like, two years later [after] it had been trying to open for about ten years.

LS: What was your role with them?

MT: My friend, [Kyle Bravo], was managing it like one hour a week. And then he was leaving and I had interned for him post-Katrina. He taught me letterpress and I helped scrape the rust off of his letterpress machine and helped him proof lead type. I got [the] job by him quitting and literally being like, “And my friend’s outside and she wants to talk to you.” So I went in and I pitched how to have a community printshop and how to pay for my salary in two years, which was a boldfaced lie. I don’t know anything about accounting. And they were like, “Sure.” And then they ran out of money.

They had state of the art glass blowing, ceramics, and a forge. They had everything, and none of the things happened because they had no money to pay for teachers. And then I was just in there like, “Okay. Well if there’s no money then I’m just giving keys to punks and then they’re going to teach free classes and we’re just going to do this radical workshop.” That lasted about a year and a half and gave me about ten thousand heart attacks because I was twenty-four and didn’t know what I was doing.

[But] I ended up here [so] it was great. At the time I was photographing mostly abandoned industrial architecture because that is what I love to go explore in Rhode Island and it was kind of classic like, go on a bike ride, have a crush, explore this abandoned building. I thought of them as wonderful places to explore, play, sometimes have parties and shows; very, like, New England 90s punk… [I] didn’t quite examine the total privilege of not being afraid of getting arrested in those spaces. But I really loved them. They always made me feel calm and full of love. There’s this place down here I photographed for a couple years called the Market Street Power Station. It’s still there. It’s up on Tchoupitoulas and Race. It’s the huge smoke stacks you can see when you go over the Twin Span. I just photographed those over and over because it’s wildly photogenic. I became friends with the security guard.

But the better I got at photographing, the more I just felt like urban decay was just missing the heart of it…I wouldn’t say I came here seeking community because I would say I enjoy building it wherever I am. But I found a really incredible community here—this amazing combination of teachers and artists and sex workers all just trying to live here. Especially because it was post-Katrina, people were really just trying to stay here and live here and love it and build and rebuild with such intention. I feel like it would be impossible to not fall in love with that kind of commitment and dedication that people had. And coming out of art school, it was so refreshing to be around people who were making art all around me, but they weren’t on that get-a-gallery, get-a-studio-visit… it was such a different art landscape, and I had never seen people costume and parade. I had never seen people play music in the street. I had never seen puppetry—this art as daily practice… I came here after my freshman year to visit, and it was definitely like, stars in the eyes… I’ve never been in a place where art was just so respected and part of everyone’s life.

LS: And how do you feel like your practice has evolved since?

MT: There was a point about ten or so years ago when I picked up this tintype process.

LS: Who taught you? How did you learn?

MT: The first person to teach me was just another punk photographer, [Dinah DiNova], who picked it up from somewhere else. She had a traveling trunk and was just taking photos of friends. She had a portrait project called “Tin, Sin, and Kinship.” And she had been photographing a lot in Ida and queer rural Tennessee. She really wanted to shoot in a way where you wouldn’t be able to tell if it was now or 1860—shooting a very visibly queer community; less costumes and more like, queers in the woods—in this effort not to make a false archive, [but to] photograph places and people that hadn’t been photographed or [recreate] photographs had been lost or destroyed. I learned a lot from her, not just about the chemistry, but watching how she was using a historic medium and why.

She hired this guy from Mississippi to teach me. And I was like, “This is the best way to learn.” And eventually, she liked doing them with an enlarger—not in the camera. Through that I got to learn. And so, learning from Dinah and struggling with this architecture photography and thinking, “I have so much love for these places,” and for me, they’re about how I feel in them, but it wasn’t meshing. I had friends go with me. I basically started photographing the people around me… because a building isn’t like, “Oh my god I look so great in that photograph.” I had been a drawer. Architecture, right? And so watching somebody else discover themself in a photograph was just such a revelation, especially because it’s instant and because it’s not like I’m shooting film and then ten weeks later I give you photographs. And digital—most people hate how they look. It’s just too much. The tintypes have this beautiful view. It’s so transformative. To watch people just be like, “Oh. That’s me.” I was like, “This is a superpower.” That was a first body of work—collaborative portraits that were around like, is there an archetype or previous photograph or something you’ve seen before that you’re trying to evoke or capture about your power or your gender or your beauty or your sexuality? We would talk for weeks or years about what’s the photo.

For the second film fest for [Always for Pleasure], we set up a porn studio. That was the first time I was like, “Oh this is so fun.” We were creating this environment, and we wanted it to be sexy but it doesn’t feel extractive. People feel sexy, they feel safe, they feel ownership. It took me a long time to then feel comfortable directing people… only now can I get more into having pseudo-narratives.