“Do you mind if I touch your eyeballs?”

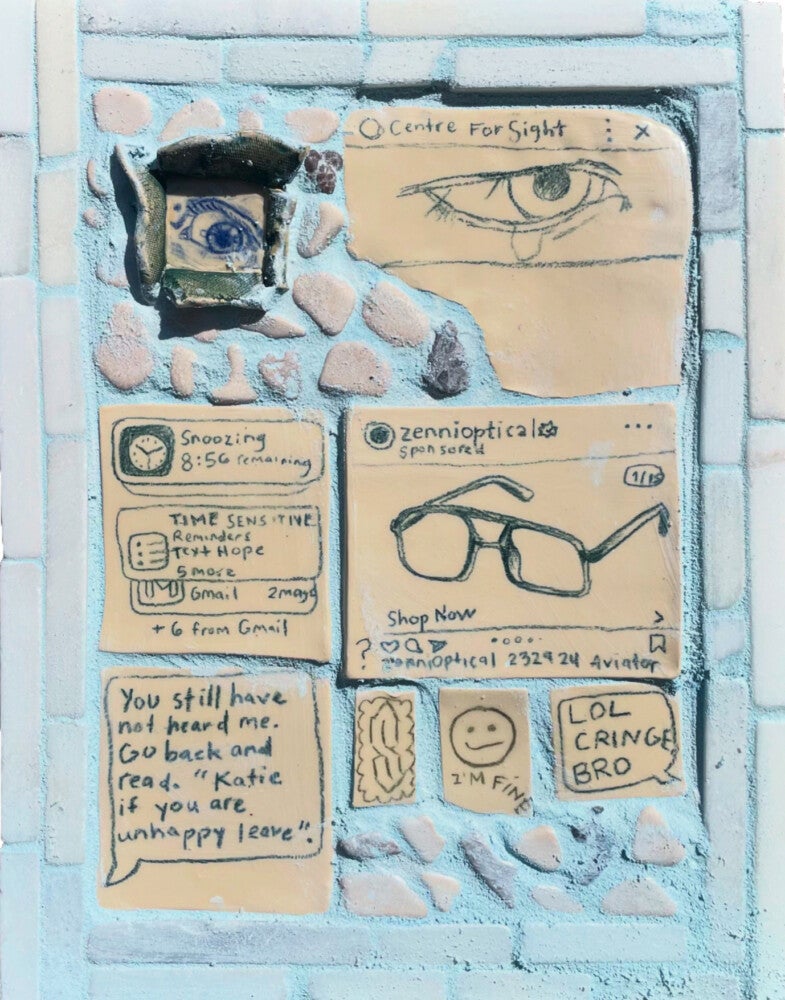

I’m kneeling over a cardboard box filled with ceramic tiles. They are the excess from a massive installation Kate Burke made for Atlanta Contemporary in 2023 titled It Doesn’t Keep You Warm, in which hundreds of women’s eyes painted on ceramic tiles gazed out into an outdoor courtyard. Fresh off three months at the Long Meadow Arts Residency in Massachusetts, Kate is still unpacking boxes. Some are filled with ceramic pieces, others with fabric and found oddities. The eye tiles—which Kate graciously allowed me to dig through—are being placed along the border of a new piece.

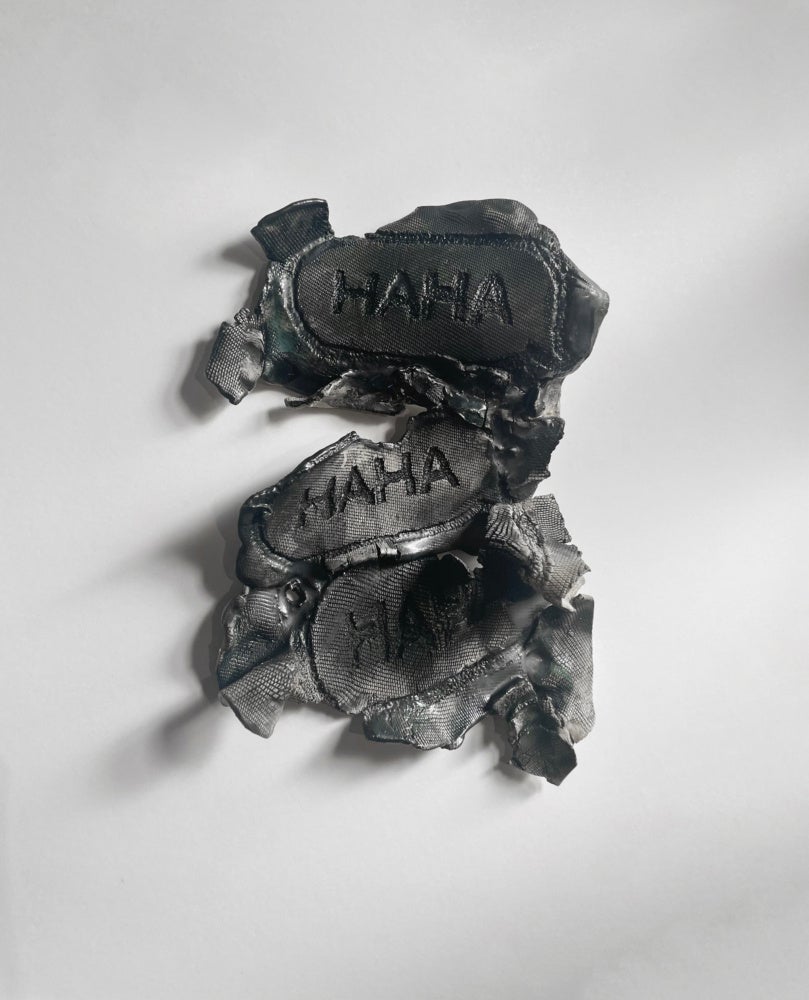

Kate’s work constantly oscillates between mediums, thematics, and levels of emotional punch. She references social media imagery, the universality and strangeness of online life, and break-up texts. Her works are often personal, drawing from her childhood experiences and using texts, materials, and anecdotes from her life. Sometimes her works are cute and playful, like her small ceramic magnets with green hand-drawn flowers and flirty little Kate-isms such as “Open Me <3” and “Sex Sym-Bol.” Beneath and between the winks and the sighs is a serious theoretic foundation and deep questions concerning what is reality, what is fiction, and who gets to decide. During my visit to her Atlanta Contemporary studio, we discussed the relationship between time and craft, the unspoken rules of social media, and how to confront the new Gods of the digital age.

EC Flamming: You consistently employ elements of craft-making in your work. What does craft mean to you? What does crafting mean in a contemporary context?

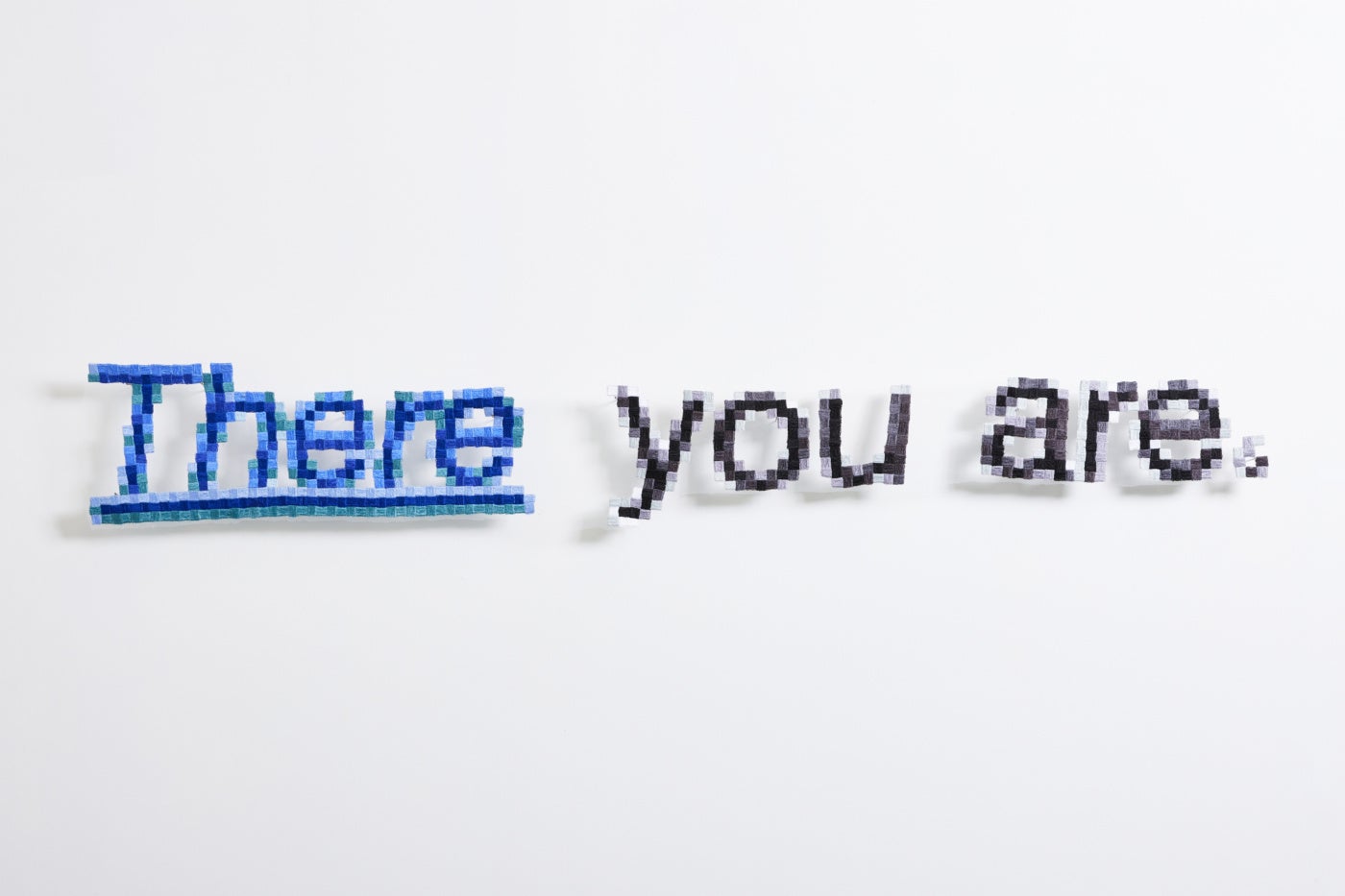

Kate Burke: Craft uses the medium of time within it. With the idea of time, in this day and age, we feel like we don’t have a lot of it and that it is very fleeting, or it is something to be grasped. I love the idea of sitting and making something with my full intention and attention. There’s something very beautiful in taking the time to make something a craft object.

ECF: You use all these different materials—textiles, ceramics, writing, woodblocks, Perler beads, found objects, and digital screenshots—in surprising ways. For example, when you print out Instagram screenshots onto ceramics, one of the most ancient mediums. What is your thought process around these kinds of choices?

KB: I think medium becomes interesting when you start to work with the duality of the idea, like the opposite side of the coin. When it comes to using and talking about digital media, through the lens of craft and ceramic, it’s important and exciting because these digital experiences that we engage with on a day-to-day basis are seemingly insignificant. We can take this ephemeral phone object and put it in our pocket and walk away.

When it comes to digital experiences, you have this rigid yet fragile medium that is breakable, moldable, and bendable, which gives it this physical quality. We can start to take these intangible ideas and notice the physicality of them, whether or not by engaging with it on a wall through my work, or interiorly recognizing that the time I spend on my device actually does have a spiritual impact.

ECF: Spirituality, and your religious upbringing, specifically your experience growing up in a strict religious household and then later leaving that culture, are often referenced in your work. Could you talk about how your past religious experiences influence your work now?

KB: I graduated from college and recognized that I was diverting from a lot of these specific ideas that I had been handed growing up. Ultimately, I left in search of some other spiritual aspect through a process called deconstruction.

As I was exploring those thoughts, I recognized that a lot of the reverberations that I experienced in Christianity started to pop up in my digital experiences, like questions about my sense of self and my identity. Instead of being viewed through the lens of God or the church, I’m now viewed through the lens of my Instagram presence. I started to understand and see that this medium of social media was just that: a medium. It could also be viewed as some sort of religious framework.

ECF: Yes—the spoken or unspoken rules of a digital space can have some overlap with religion in terms of the enforcement of norms, what’s acceptable, what isn’t, how it functions as a community, and how it’s so consuming.

KB: You can take the idea of storytelling and put yourself in the God seat in social media, because you can create the story, you can curate the image, you can censor the comments, you can manipulate and story-tell. On top of that, you have algorithmic echo chambers. It’s very similar to my past experiences with Christianity. That’s what I picked up on and what I’ve been trying to iron out.

ECF: There is a piece on the floor right now that you were in the process of spray-painting hot pink and arranging found objects on when I first walked in the studio. Could you tell me more about it?

KB: This piece is going to be titled something like “digital storage 101: the things I saved that saved me.” In Christian jargon, there is this very big question: are you saved? In the process of my spiritual journey, I have gone through iterations of seeking and organizing information digitally, just sorting who I am and what I think and how I can be the type of person I want to be. When I was at Long Meadow Arts Residency, I would go thrifting and find objects that I was really drawn to, recognizing that these objects were calling back to a childlike sense of wonder. I’m trying to recontextualize my past fascinations of true love and these fairy tale moments of what love could look like through the lens of the digital era that we live in.

ECF: One thing people might not know about you is that you’re a musician. You play the flute, you’re a very musical person.

KB: Ensemble and collaboration is my favorite activity ever. I will just be a performer at some point in my life. Sure, I’ll always be an artist, but I can be a musician who does these strange performances with visual aspects. I have some shows coming up where I think I will be making flute sounds with ceramic vessels and creating these sonic orchestras for people to experience. One of them is a two-person show with Aineki Traverso at the Spruill Gallery, which is where I hope to have one of these ceramic orchestras.