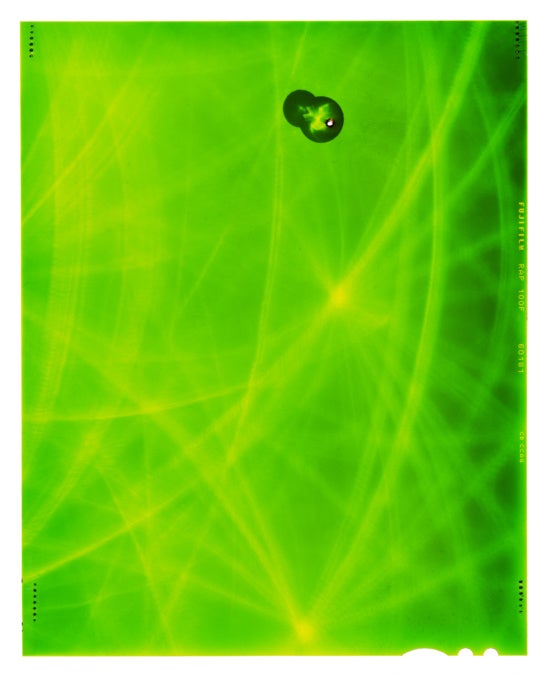

Born in Pompano Beach, Florida, Julia García’s painting process derives from her experience of living in close proximity to the Everglades wetlands. Drawing on the permeability of the Florida landscape, García mimes Florida’s refusal of exacting definition by diffusing water-based pigments on wet, raw canvas. Blurring the bounds of human and environment, of memory and the present, of power and desire, García questions what sense can be made of all that is left behind.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Charlotte Foreman: Could you share how you developed a painting process so deeply connected to water?

Julia Garcia: I was working with imagery that had more of a Floridian feeling, and thinking about how the bedrock of the state is so porous and absorbent. It felt related to the open canvas and the use of all this water I had. To control that, I was using a lot of tape, which felt like flying on a plane and seeing all the cordoned-off areas, whether it be an urban development or resource extraction project, all these shapes being made into the wetland. I work flat on the ground to control the water, rather than having everything slide off the surface. It felt rooted in the landscape I had grown up in and was really familiar with; a hurricane might swell the tiny creek behind a house into the pool, and then there’s a little alligator in the pool. That would happen to my grandma all the time. Learning to navigate living with the water that is so present in the landscape, because despite all the development, there’s an inability to actually separate oneself from it. Everything just spills over. I’m very interested in this blurring of boundaries, of where things end and others begin.

CF: Your 2023 exhibition Sawgrass at Night Club Gallery in St. Paul, Minnesota showcases a series of paintings depicting bikini-clad women and alligators in striking, suggestive poses—straddling them or posing with them over their shoulders. What drew you to the “bikini bowhunter” trend that inspired these works?

JG: One of the things I’m fundamentally interested in is how desire functions to motivate or interest people, and what the power structure of the gaze really is. I stumbled across these images of girls in bikinis wrestling alligators, or hunting them, and trophy posing with their bodies. It was almost pornographic. They’re not in big T-shirts with no makeup—no, they are almost campily feminine in these tiny bikinis. It had this very traditional sense of I can do this thing, but I’m still womanly, capital W. It seemed really fascinating that there would be an audience for this type of content. I’m sure some people are doing it because it makes them feel empowered to confront something really ancient. Maybe some people want to eat them, I’m not entirely sure. Some aspect of it was highly sexualized; there were calendars and paywalled videos, implying there was this desire to watch. I think what most interested me to begin with was that it existed, but also that the audience existed, and what the dynamic was between the content being made and it being consumed. What does it mean to want to see this young, nubile body, crouched over an ancient beast? It was all really very contrasting—that relationship of human beings and nature, of life and death, erotic drive, death drive, and danger. A fascinating jumble of things in an image.

CF: How do you source your subject matter?

JG: I spend a lot of time surfing through pictures, collecting source imagery. Whether I’m going through an archive, a library, through lots of slides on eBay, or just random deep Google Image Search holes, it is an image-based research. Slides and stock images, it’s a mix of both. It’s people’s personal nostalgic memories, but very placeless.

It’s interesting these types of things end up democratized by the internet. They’re really personal, and it’s crazy being able to just buy something that at some point was somebody’s treasured snapshot of a moment. Now it’s been completely decontextualized–you don’t know who they are, you don’t know what happened before or after. It’s like, if you were to look through a history book, but all the text was gone, and you had to make up the relationships between the images. How will things be uncovered from now if there was somehow a loss of the data that we use to explain them?

CF: Your generous use of water in your work, that softening of hard edges, really evokes the way memory diffuses and blurs over time.

JG: That’s part of why technically working in this way is so interesting to me. First of all, it’s fun, because it’s hard to control, it’s really unpredictable, and I enjoy that experience. I really feel like it’s so deeply tied to all these things in the imagery. If the paintings were given time, all these really strange connections would begin to make sense, with the material and then with the subjects and how they are interacted with and how they exist. It has this immediate absorption and almost feels like watercolor or fresco, like the image is not sitting on top, but rather settling into the material.

CF: Is the process you use archival?

JG: It is archival, except in some areas where I use a powder-based fabric dye that can be reactivated by water, which is always a little bit nerve-wracking when it is being shipped somewhere. Most of the other mark-making is either acrylic ink or acrylic paint.

It happened once, when something was going down to Florida for the NADA show at Art Basel. There was a really bad storm, and water got into the crate and moved some stuff around. It ended up being fine. I looked at it and I was like, actually, I think that rainstorm just finished that painting for me. It was a really strange feeling of this external force, this natural force outside of any kind of control. That’s part of working with water–really embracing that and surrendering to its properties. You look away for a second, and it does something that you can’t come back from, and you just have to adjust and pivot.